Clifton Mark in Aeon:

In 1717, Voltaire was arrested, some might say, for giving offence. He had published a ‘satirical’ verse that opens by calling the Duc d’Orleans, the then Regent of France, ‘an inhuman tyrant, famous for poison, atheism, and incest’. This pungent personal attack became so popular it was sung on the streets of Paris. In response, the Duc had Voltaire arrested without accusation or trial. The author spent 11 months in the Bastille.

In 1717, Voltaire was arrested, some might say, for giving offence. He had published a ‘satirical’ verse that opens by calling the Duc d’Orleans, the then Regent of France, ‘an inhuman tyrant, famous for poison, atheism, and incest’. This pungent personal attack became so popular it was sung on the streets of Paris. In response, the Duc had Voltaire arrested without accusation or trial. The author spent 11 months in the Bastille.

Such stories help to explain why Voltaire turns up so frequently in today’s debates over offensive speech, which are driven by the sense that members of historically marginalised groups have become increasingly willing to take offence to speech that they feel implies their exclusion or inferiority. Many believe that this trend has gone too far. In 2016, the Pew Research Centre in the US found that a majority of Americans believe that ‘too many people are easily offended these days over language’. Angus Reid, a Canadian polling company, found similar results – in their poll, 80 per cent of Canadians agreed with the statement: ‘These days, it seems like you can’t say anything without someone feeling offended.’ This sense is not without basis. Public discourse is filled with confrontations over offensive speech. Hardly a day goes by when some public figure is not called out for offensive behaviour, or when another argues that all this offence-taking is a threat to free speech.

More here.

Economics, like other sciences (social and otherwise), is about what the world does; but it’s natural for economists to occasionally wander out into the question of what we should do as we live in the world. A very good example of this is a new book by economist Tyler Cowen,

Economics, like other sciences (social and otherwise), is about what the world does; but it’s natural for economists to occasionally wander out into the question of what we should do as we live in the world. A very good example of this is a new book by economist Tyler Cowen,  Was Sharmila Sen “happy” on the first morning she woke up in the United States to the strange smell of bacon frying? That’s what her young son wants to know when, near the end of Not Quite Not White—Sen’s powerful memoir and meditation on race and migration—he interviews her for a school project on immigration. It turns out we already know the answer. “It was a complex animal smell,” we read earlier of the odor she ever after associates with her 1982 arrival in Boston from Calcutta, “making my mouth water and my stomach churn in revulsion at the same time.”

Was Sharmila Sen “happy” on the first morning she woke up in the United States to the strange smell of bacon frying? That’s what her young son wants to know when, near the end of Not Quite Not White—Sen’s powerful memoir and meditation on race and migration—he interviews her for a school project on immigration. It turns out we already know the answer. “It was a complex animal smell,” we read earlier of the odor she ever after associates with her 1982 arrival in Boston from Calcutta, “making my mouth water and my stomach churn in revulsion at the same time.” Princess Mononoke inaugurated a new chapter in Miyazakiworld. Ambitious and angry, it expressed the director’s increasingly complex worldview, putting on film the tight intermixture of frustration, brutality, animistic spirituality, and cautious hope that he had honed in his manga Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. The film offers a mythic scope, unprecedented depictions of violence and environmental collapse, and a powerful vision of the sublime, all within the director’s first-ever attempt at a jidaigeki, or historical film. It also moves further away from the family fare that had made him a treasured household name in Japan.

Princess Mononoke inaugurated a new chapter in Miyazakiworld. Ambitious and angry, it expressed the director’s increasingly complex worldview, putting on film the tight intermixture of frustration, brutality, animistic spirituality, and cautious hope that he had honed in his manga Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. The film offers a mythic scope, unprecedented depictions of violence and environmental collapse, and a powerful vision of the sublime, all within the director’s first-ever attempt at a jidaigeki, or historical film. It also moves further away from the family fare that had made him a treasured household name in Japan. The publication of Cynthia Haven’s full-dress biography of René Girard, a major figure in the “French invasion” that stormed the beaches of American academe across the final decades of the last millennium, marks a notable event on many fronts: academic, professional, literary, philosophical; and for some individuals among generations of students world-wide, deeply personal. In my case, that means religious.

The publication of Cynthia Haven’s full-dress biography of René Girard, a major figure in the “French invasion” that stormed the beaches of American academe across the final decades of the last millennium, marks a notable event on many fronts: academic, professional, literary, philosophical; and for some individuals among generations of students world-wide, deeply personal. In my case, that means religious. It is unpleasant to feel alone. Loneliness can be a source of desolation and anguish. That is why it is understandable that many of us look for ways to fix it. Some seek out therapy, others join social clubs and attempt to forge new relationships and contacts. The refusal to accept social isolation and the search for solidarity shapes who we are and influences community life. Loneliness is not just a condition that we must suffer. It also provides people with an opportunity to gain an understanding of themselves and of their world. The theologian Paul Tillich exhorted people to embrace their loneliness, because it forces us to engage with life’s two most fundamental questions: what is the meaning of life and how should we understand ourselves?

It is unpleasant to feel alone. Loneliness can be a source of desolation and anguish. That is why it is understandable that many of us look for ways to fix it. Some seek out therapy, others join social clubs and attempt to forge new relationships and contacts. The refusal to accept social isolation and the search for solidarity shapes who we are and influences community life. Loneliness is not just a condition that we must suffer. It also provides people with an opportunity to gain an understanding of themselves and of their world. The theologian Paul Tillich exhorted people to embrace their loneliness, because it forces us to engage with life’s two most fundamental questions: what is the meaning of life and how should we understand ourselves? Édouard Vuillard was 60 when his mother died in 1928. He had never lived with anybody else. “My mother is my muse,” he confessed to a friend, and the truth of that is apparent in more than 500 images of this small, stout widow with her tight bun and patterned dresses running a sewing business in the various Paris apartments they shared. She is there from first to last.

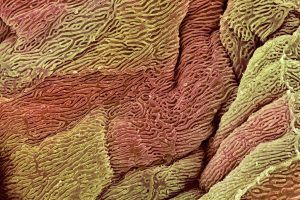

Édouard Vuillard was 60 when his mother died in 1928. He had never lived with anybody else. “My mother is my muse,” he confessed to a friend, and the truth of that is apparent in more than 500 images of this small, stout widow with her tight bun and patterned dresses running a sewing business in the various Paris apartments they shared. She is there from first to last. Cancer is a disease of mutations. Tumor cells are riddled with genetic mutations not found in healthy cells. Scientists estimate that it takes five to 10 key mutations for a healthy cell to become cancerous. Some of these mutations can be caused by assaults from the environment, such as ultraviolet rays and cigarette smoke. Others arise from harmful molecules produced by the cells themselves. In recent years, researchers have begun taking a closer look at these mutations, to try to understand how they arise in healthy cells, and what causes these cells to later erupt into full-blown cancer. The research has produced some major surprises. For instance, it turns out that a large portion of the cells in healthy people carry far more mutations than expected, including some mutations thought to be the prime drivers of cancer. These mutations make a cell grow faster than others, raising the question of why full-blown cancer isn’t far more common. “This is quite a fundamental piece of biology that we were unaware of,” said Inigo Martincorena, a geneticist at the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Cambridge, England.These lurking mutations went unnoticed for so long because the tools for examining DNA were too crude. If scientists wanted to sequence the entire genome of tumor cells, they had to gather millions of cells and analyze all of the DNA. A mutation, to be detectable, had to be very common.

Cancer is a disease of mutations. Tumor cells are riddled with genetic mutations not found in healthy cells. Scientists estimate that it takes five to 10 key mutations for a healthy cell to become cancerous. Some of these mutations can be caused by assaults from the environment, such as ultraviolet rays and cigarette smoke. Others arise from harmful molecules produced by the cells themselves. In recent years, researchers have begun taking a closer look at these mutations, to try to understand how they arise in healthy cells, and what causes these cells to later erupt into full-blown cancer. The research has produced some major surprises. For instance, it turns out that a large portion of the cells in healthy people carry far more mutations than expected, including some mutations thought to be the prime drivers of cancer. These mutations make a cell grow faster than others, raising the question of why full-blown cancer isn’t far more common. “This is quite a fundamental piece of biology that we were unaware of,” said Inigo Martincorena, a geneticist at the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Cambridge, England.These lurking mutations went unnoticed for so long because the tools for examining DNA were too crude. If scientists wanted to sequence the entire genome of tumor cells, they had to gather millions of cells and analyze all of the DNA. A mutation, to be detectable, had to be very common.

A bit of self indulgence – also a kind of preface to all the 3 Quarks Daily

A bit of self indulgence – also a kind of preface to all the 3 Quarks Daily

Two weeks ago, Maniza Naqvi evocatively wrote here on the resonance of a mythological rape in the eventual confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh to the US Supreme Court (

Two weeks ago, Maniza Naqvi evocatively wrote here on the resonance of a mythological rape in the eventual confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh to the US Supreme Court ( Middle age brings sometimes uncomfortable self-reflection. One thing I have realized is that I am not a particularly good person. Not evil, just mediocre. Lots of people are much better at morality than me, including many of my students. On the other hand, I am quite good at the academic subject of ethics. Good enough to teach it at a university and write papers that occasionally appear in nice journals.

Middle age brings sometimes uncomfortable self-reflection. One thing I have realized is that I am not a particularly good person. Not evil, just mediocre. Lots of people are much better at morality than me, including many of my students. On the other hand, I am quite good at the academic subject of ethics. Good enough to teach it at a university and write papers that occasionally appear in nice journals. How conceivable is this? Trump loses the 2020 US presidential election. But he refuses to concede, claiming that results in the swing states of Ohio and Florida were invalid due to voter fraud and crooked election officials. Fox News, other right-wing media and the Republican controlled congress go along with this. So Trump remains president until, in the words of Senate leader Mitch McConnell, “we are able to clear up this mess.” Clearing up the mess, it turns out, could take some time–even longer than it takes for Trump to fulfill his promise to release his tax returns. Law suits are brought, but guess what? By a 5 to 4 majority, the supreme court refuses to hear them.

How conceivable is this? Trump loses the 2020 US presidential election. But he refuses to concede, claiming that results in the swing states of Ohio and Florida were invalid due to voter fraud and crooked election officials. Fox News, other right-wing media and the Republican controlled congress go along with this. So Trump remains president until, in the words of Senate leader Mitch McConnell, “we are able to clear up this mess.” Clearing up the mess, it turns out, could take some time–even longer than it takes for Trump to fulfill his promise to release his tax returns. Law suits are brought, but guess what? By a 5 to 4 majority, the supreme court refuses to hear them.

What unites Mark Zuckerberg and the Koch Brothers? For many, their politics appear to set them apart. At least before the Cambridge Analytica revelations of last spring, Zuckerberg seemed the darling of a certain kind of liberal, announcing on Oprah Winfrey’s television show that he planned to spend $100 million to fix the Newark school system, declaring (in a talk at the University of California, San Francisco) that he plans to use his limited-liability philanthropic corporation to “cure, prevent or manage all diseases,” promising to use his vast riches to help create “a future for everyone,” as the promotional materials for the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative put it—all of which led his name to be batted about as a possible Democratic presidential candidate in 2020. The oil magnate Kochs, on the other hand—leading supporters of libertarian political organizations like Americans for Prosperity—have become synonymous with “dark money” efforts by elusive billionaires to push right-wing politics.

What unites Mark Zuckerberg and the Koch Brothers? For many, their politics appear to set them apart. At least before the Cambridge Analytica revelations of last spring, Zuckerberg seemed the darling of a certain kind of liberal, announcing on Oprah Winfrey’s television show that he planned to spend $100 million to fix the Newark school system, declaring (in a talk at the University of California, San Francisco) that he plans to use his limited-liability philanthropic corporation to “cure, prevent or manage all diseases,” promising to use his vast riches to help create “a future for everyone,” as the promotional materials for the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative put it—all of which led his name to be batted about as a possible Democratic presidential candidate in 2020. The oil magnate Kochs, on the other hand—leading supporters of libertarian political organizations like Americans for Prosperity—have become synonymous with “dark money” efforts by elusive billionaires to push right-wing politics. J.M. Coetzee: Balzac famously wrote that behind every great fortune lies a crime. One might similarly claim that behind every successful colonial venture lies a crime, a crime of dispossession. Just as in the dynastic novels of the nineteenth century the heirs of great fortunes are haunted by the crimes on which their fortunes were founded, a successful colony like Australia seems to be haunted by a history that will not go away. The question of what to say or do about dispossession of Indigenous Australians is as alive in the Australian imagination as it has ever been.

J.M. Coetzee: Balzac famously wrote that behind every great fortune lies a crime. One might similarly claim that behind every successful colonial venture lies a crime, a crime of dispossession. Just as in the dynastic novels of the nineteenth century the heirs of great fortunes are haunted by the crimes on which their fortunes were founded, a successful colony like Australia seems to be haunted by a history that will not go away. The question of what to say or do about dispossession of Indigenous Australians is as alive in the Australian imagination as it has ever been. The modern separation among scholars between intellectual history and the history of mathematics is untenable as mathematics might be the ultimate intellectual endeavour. In the words of the 19th-century German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss: ‘mathematics is the queen of the sciences’; like literacy, widespread numeracy is one of the defining features of modernity. In fact, one of the great shifts of modernity has been how mathematicians changed their view of mathematics, transforming the focus of their work from the study of the natural world to the study of ideas and concepts. Perhaps more than any other subject, mathematics is about the study of ideas. Yet, when people invoke the history of ideas, you are unlikely to hear about Dedekind’s cut (that is, the technique by which the real numbers are rigorously defined from the rational numbers), or L E J Brouwer’s rejection of Aristotle’s ‘law of excluded middle’, which states that any proposition is either true or that its negation is (put technically: for all propositions p, either p or not p). Nor are you likely to hear about the contested history of these ideas. Generally, when they talk about ideas, intellectual historians today mean political thought, cultural analysis, and maybe a sprinkling of economic and religious concepts, too.

The modern separation among scholars between intellectual history and the history of mathematics is untenable as mathematics might be the ultimate intellectual endeavour. In the words of the 19th-century German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss: ‘mathematics is the queen of the sciences’; like literacy, widespread numeracy is one of the defining features of modernity. In fact, one of the great shifts of modernity has been how mathematicians changed their view of mathematics, transforming the focus of their work from the study of the natural world to the study of ideas and concepts. Perhaps more than any other subject, mathematics is about the study of ideas. Yet, when people invoke the history of ideas, you are unlikely to hear about Dedekind’s cut (that is, the technique by which the real numbers are rigorously defined from the rational numbers), or L E J Brouwer’s rejection of Aristotle’s ‘law of excluded middle’, which states that any proposition is either true or that its negation is (put technically: for all propositions p, either p or not p). Nor are you likely to hear about the contested history of these ideas. Generally, when they talk about ideas, intellectual historians today mean political thought, cultural analysis, and maybe a sprinkling of economic and religious concepts, too.