Daniel Zamora in Jacobin:

Following the sensational success of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century, with no less than 2.5 million copies of the book sold worldwide, inequality is now widely perceived, to quote Bernie Sanders, as “the great moral issue of our time.” Clearly the shift is part of a wider transformation of American and European politics in the wake the 2008 crash that has turned the “1%” into an object of increasing attention. Marx’s Capital is now a bestseller in the “free enterprise” section of the Kindle store, Jacobin is considered a respectable place to be published, and socialism no longer looks like a failed rock band trying to climb on stage when the “party” is already over. On the contrary, if we are to believe Gloria Steinem, a Bernie Sanders rally is now the “place to be,” even “for the girls.”

Following the sensational success of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century, with no less than 2.5 million copies of the book sold worldwide, inequality is now widely perceived, to quote Bernie Sanders, as “the great moral issue of our time.” Clearly the shift is part of a wider transformation of American and European politics in the wake the 2008 crash that has turned the “1%” into an object of increasing attention. Marx’s Capital is now a bestseller in the “free enterprise” section of the Kindle store, Jacobin is considered a respectable place to be published, and socialism no longer looks like a failed rock band trying to climb on stage when the “party” is already over. On the contrary, if we are to believe Gloria Steinem, a Bernie Sanders rally is now the “place to be,” even “for the girls.”

On closer scrutiny, however, it’s not entirely clear how well our current interest in inequality (especially income inequality) rhymes with Marx’s own theory, or the ideas that dominated social-policy debates in decades following the Second World War. In fact, one could even argue that our current focus on income and wealth inequality, while crucial to any progressive agenda, also misses some of the most important aspects of the nineteenth-century critique of capitalism. At that time, “income inequality” was an elusive and at best ancillary term. In fact, the “monetization” of inequality is actually a relatively recent way of seeing the world — and, aside from its obvious strengths, it is also a way of seeing that, as the historian Pedro Ramos Pinto noted, has considerably “narrowed” the way we think about social justice.

More here.

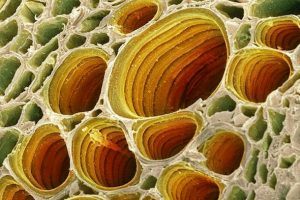

Because biology is the result of evolution and not human development, bringing engineering principles to it is guaranteed to fail. Or so goes the argument behind the “Grove fallacy,”

Because biology is the result of evolution and not human development, bringing engineering principles to it is guaranteed to fail. Or so goes the argument behind the “Grove fallacy,”  Growing up, I never considered myself to be particularly nice, perhaps because I’m from a rural part of New Brunswick, one of Canada’s Maritime Provinces—the conspicuously “nicest” region in a self-consciously nice country. My parents are nice in a way that almost beggars belief—my mother’s tact is such that the strongest condemnation in her arsenal is “Well, I wouldn’t say I don’t like it, per se…” As for me, teenage eye-rolls gave way to undergraduate seriousness, which gave way to graduate-student irony. I thought of Atlantic Canadian nice as a convenient way to avoid telling the truth about the way things are—a disingenuous evasion of the nasty truth about the world. Even the word nice seems the moral equivalent of “uninteresting”—anodyne, tedious, otiose.

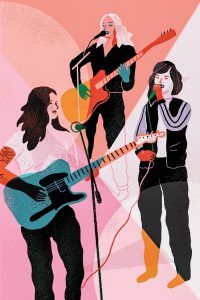

Growing up, I never considered myself to be particularly nice, perhaps because I’m from a rural part of New Brunswick, one of Canada’s Maritime Provinces—the conspicuously “nicest” region in a self-consciously nice country. My parents are nice in a way that almost beggars belief—my mother’s tact is such that the strongest condemnation in her arsenal is “Well, I wouldn’t say I don’t like it, per se…” As for me, teenage eye-rolls gave way to undergraduate seriousness, which gave way to graduate-student irony. I thought of Atlantic Canadian nice as a convenient way to avoid telling the truth about the way things are—a disingenuous evasion of the nasty truth about the world. Even the word nice seems the moral equivalent of “uninteresting”—anodyne, tedious, otiose. In 2016, the singer-songwriters Julien Baker, Lucy Dacus, and Phoebe Bridgers, who were all in their early twenties, were living parallel lives. They’d proved themselves to be careful and accomplished writers and performers, and had begun to attract attention from critics and labels alike. Each artist had crafted a distinct sound: Baker, a recovered opioid addict from Memphis, whose musical upbringing was in the Christian church, makes spare and swelling music that draws from the melodies and the ritualized melancholy of the emo world. Bridgers, a Los Angeles native who worshipped

In 2016, the singer-songwriters Julien Baker, Lucy Dacus, and Phoebe Bridgers, who were all in their early twenties, were living parallel lives. They’d proved themselves to be careful and accomplished writers and performers, and had begun to attract attention from critics and labels alike. Each artist had crafted a distinct sound: Baker, a recovered opioid addict from Memphis, whose musical upbringing was in the Christian church, makes spare and swelling music that draws from the melodies and the ritualized melancholy of the emo world. Bridgers, a Los Angeles native who worshipped  Who was the main enemy now? On the right, the answer increasingly was one another. In the 1980s, the conservative movement split into two warring factions—neoconservatives and paleo conservatives. The two sects fought over ideas, but also resources: comfortable think tank positions and administrative posts; grant money and the allegiance of the idle army of increasingly ideologically restive conservative activists who could scare up campaign contributions and votes.

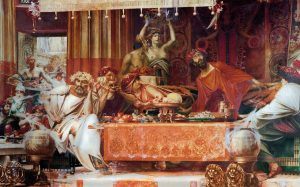

Who was the main enemy now? On the right, the answer increasingly was one another. In the 1980s, the conservative movement split into two warring factions—neoconservatives and paleo conservatives. The two sects fought over ideas, but also resources: comfortable think tank positions and administrative posts; grant money and the allegiance of the idle army of increasingly ideologically restive conservative activists who could scare up campaign contributions and votes. “Before the bedroom there was the room, before that almost nothing”, Perrot announces. She chooses to leapfrog over much medieval history and begin with a description of the king’s bedroom at Versailles under Louis XIV – an account for which she relies heavily on the memoirs of the duc de Saint-Simon, who spoke to the Sun King twice. Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie is more thorough as an interpreter of the stultifying etiquette of the Versailles system, and Nancy Mitford much funnier; there is no fresh research or information in Perrot’s summary, which is at best indecisive as to the significance of the royal bedroom: “the king’s chamber guards its mysteries”. That said, we learn that Perrot intends to trace the origin of the desire for a “room of one’s own”, which mark of individualization is apparently less universal than it might appear. The Japanese had no notion of privacy, we are told, which might have come as news to the ukiyo-e artists of the seventeenth century; nonetheless, Perrot is broadly correct in her account of the evolution of private sleeping space as depending on the movement from curtained or boxed beds to separate chambers during the same period in Europe.

“Before the bedroom there was the room, before that almost nothing”, Perrot announces. She chooses to leapfrog over much medieval history and begin with a description of the king’s bedroom at Versailles under Louis XIV – an account for which she relies heavily on the memoirs of the duc de Saint-Simon, who spoke to the Sun King twice. Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie is more thorough as an interpreter of the stultifying etiquette of the Versailles system, and Nancy Mitford much funnier; there is no fresh research or information in Perrot’s summary, which is at best indecisive as to the significance of the royal bedroom: “the king’s chamber guards its mysteries”. That said, we learn that Perrot intends to trace the origin of the desire for a “room of one’s own”, which mark of individualization is apparently less universal than it might appear. The Japanese had no notion of privacy, we are told, which might have come as news to the ukiyo-e artists of the seventeenth century; nonetheless, Perrot is broadly correct in her account of the evolution of private sleeping space as depending on the movement from curtained or boxed beds to separate chambers during the same period in Europe. According to David Wootton, we are living in a world created by an intellectual revolution initiated by three thinkers in the 16th to 18th centuries. “My title is, Power, Pleasure and Profit, in that order, because power was conceptualised first, in the 16th century, by Niccolò Machiavelli; in the 17th century Hobbes radically revised the concepts of pleasure and happiness; and the way in which profit works in the economy was first adequately theorised in the 18th century by Adam Smith.” Before these thinkers, life had been based on the idea of a summum bonum – an all-encompassing goal of human life. Christianity identified it with salvation, Greco-Roman philosophy with a condition in which happiness and virtue were one and the same. For both, human life was complete when the supreme good was achieved.

According to David Wootton, we are living in a world created by an intellectual revolution initiated by three thinkers in the 16th to 18th centuries. “My title is, Power, Pleasure and Profit, in that order, because power was conceptualised first, in the 16th century, by Niccolò Machiavelli; in the 17th century Hobbes radically revised the concepts of pleasure and happiness; and the way in which profit works in the economy was first adequately theorised in the 18th century by Adam Smith.” Before these thinkers, life had been based on the idea of a summum bonum – an all-encompassing goal of human life. Christianity identified it with salvation, Greco-Roman philosophy with a condition in which happiness and virtue were one and the same. For both, human life was complete when the supreme good was achieved. Of the many small humiliations heaped on a young oncologist in his final year of fellowship, perhaps this one carried the oddest bite: A 2-year-old black-and-white cat named Oscar was apparently better than most doctors at predicting when a terminally ill patient was about to die. The story appeared, astonishingly, in The New England Journal of Medicine in the summer of 2007. Adopted as a kitten by the medical staff, Oscar reigned over one floor of the Steere House nursing home in Rhode Island. When the cat would sniff the air, crane his neck and curl up next to a man or woman, it was a sure sign of impending demise. The doctors would call the families to come in for their last visit. Over the course of several years, the cat had curled up next to 50 patients. Every one of them died shortly thereafter. No one knows how the cat acquired his formidable death-sniffing skills. Perhaps Oscar’s nose learned to detect some unique whiff of death — chemicals released by dying cells, say. Perhaps there were other inscrutable signs. I didn’t quite believe it at first, but Oscar’s acumen was corroborated by other physicians who witnessed the prophetic cat in action. As the author of the article wrote: “No one dies on the third floor unless Oscar pays a visit and stays awhile.”

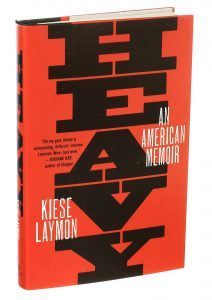

Of the many small humiliations heaped on a young oncologist in his final year of fellowship, perhaps this one carried the oddest bite: A 2-year-old black-and-white cat named Oscar was apparently better than most doctors at predicting when a terminally ill patient was about to die. The story appeared, astonishingly, in The New England Journal of Medicine in the summer of 2007. Adopted as a kitten by the medical staff, Oscar reigned over one floor of the Steere House nursing home in Rhode Island. When the cat would sniff the air, crane his neck and curl up next to a man or woman, it was a sure sign of impending demise. The doctors would call the families to come in for their last visit. Over the course of several years, the cat had curled up next to 50 patients. Every one of them died shortly thereafter. No one knows how the cat acquired his formidable death-sniffing skills. Perhaps Oscar’s nose learned to detect some unique whiff of death — chemicals released by dying cells, say. Perhaps there were other inscrutable signs. I didn’t quite believe it at first, but Oscar’s acumen was corroborated by other physicians who witnessed the prophetic cat in action. As the author of the article wrote: “No one dies on the third floor unless Oscar pays a visit and stays awhile.” Kiese Laymon started his new memoir, “Heavy,” with every intention of writing what his mother would have wanted — something profoundly uplifting and profoundly dishonest, something that did “that old black work of pandering” to American myths and white people’s expectations. His mother, a professor of political science, taught him that you need to lie as a matter of course and, ultimately, to survive; honesty could get a black boy growing up in Jackson, Miss., not just hurt but killed. He wanted to do what she wanted. But then he didn’t.

Kiese Laymon started his new memoir, “Heavy,” with every intention of writing what his mother would have wanted — something profoundly uplifting and profoundly dishonest, something that did “that old black work of pandering” to American myths and white people’s expectations. His mother, a professor of political science, taught him that you need to lie as a matter of course and, ultimately, to survive; honesty could get a black boy growing up in Jackson, Miss., not just hurt but killed. He wanted to do what she wanted. But then he didn’t. I don’t really have heroes, but if I did, Noam Chomsky would be at the top of my list. Who else has achieved such lofty scientific and moral standing? Linus Pauling, perhaps, and Einstein. Chomsky’s arguments about the roots of language, which he first set forth in the late 1950s, triggered a revolution in our modern understanding of the mind. Since the 1960s, when he protested the Vietnam War, Chomsky has also been a ferocious political critic, denouncing abuses of power wherever he sees them. Chomsky, who turns 90 on December 7, remains busy. He spent last month in Brazil speaking out against far-right politician

I don’t really have heroes, but if I did, Noam Chomsky would be at the top of my list. Who else has achieved such lofty scientific and moral standing? Linus Pauling, perhaps, and Einstein. Chomsky’s arguments about the roots of language, which he first set forth in the late 1950s, triggered a revolution in our modern understanding of the mind. Since the 1960s, when he protested the Vietnam War, Chomsky has also been a ferocious political critic, denouncing abuses of power wherever he sees them. Chomsky, who turns 90 on December 7, remains busy. He spent last month in Brazil speaking out against far-right politician  Language comes naturally to us, but is also deeply mysterious. On the one hand, it manifests as a collection of sounds or marks on paper. On the other hand, it also conveys meaning – words and sentences refer to states of affairs in the outside world, or to much more abstract concepts. How do words and meaning come together in the brain? David Poeppel is a leading neuroscientist who works in many areas, with a focus on the relationship between language and thought. We talk about cutting-edge ideas in the science and philosophy of language, and how researchers have just recently climbed out from under a nineteenth-century paradigm for understanding how all this works.

Language comes naturally to us, but is also deeply mysterious. On the one hand, it manifests as a collection of sounds or marks on paper. On the other hand, it also conveys meaning – words and sentences refer to states of affairs in the outside world, or to much more abstract concepts. How do words and meaning come together in the brain? David Poeppel is a leading neuroscientist who works in many areas, with a focus on the relationship between language and thought. We talk about cutting-edge ideas in the science and philosophy of language, and how researchers have just recently climbed out from under a nineteenth-century paradigm for understanding how all this works. If anxiety about

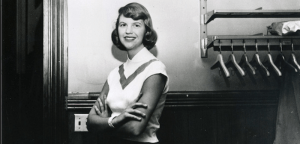

If anxiety about In Plath we have a unique example of rapid, surging development of a poet’s art. In only seven years—from 1956, when the first poems in her Collected Poems were written, to 1963, the year of her death—Plath went from being an obviously talented and excruciatingly ambitious (as her journals attest) apprentice poet with lots of technique and intensity but few real subjects on which to train those powers, to the author of unprecedented works of genius. In Plath’s first book, The Colossus and Other Poems, the only book of poetry she published in her lifetime, we have an unusual opportunity to pinpoint the moments when her art surges forward in particular poems—we can actually watch her grow as an artist, see a little bit how the magic trick was done, and perhaps learn from it. Plath’s earlier poems have a lot to teach about how poets expand their capacities, how they “find” a voice by listening closely to their own minds, and how genius can be, if not made, then at least willfully courted.

In Plath we have a unique example of rapid, surging development of a poet’s art. In only seven years—from 1956, when the first poems in her Collected Poems were written, to 1963, the year of her death—Plath went from being an obviously talented and excruciatingly ambitious (as her journals attest) apprentice poet with lots of technique and intensity but few real subjects on which to train those powers, to the author of unprecedented works of genius. In Plath’s first book, The Colossus and Other Poems, the only book of poetry she published in her lifetime, we have an unusual opportunity to pinpoint the moments when her art surges forward in particular poems—we can actually watch her grow as an artist, see a little bit how the magic trick was done, and perhaps learn from it. Plath’s earlier poems have a lot to teach about how poets expand their capacities, how they “find” a voice by listening closely to their own minds, and how genius can be, if not made, then at least willfully courted. Disregarding the substance of populism and focusing exclusively on its exclusionary rhetoric may succeed in protecting the definition of populism from everyday polemic, however it also allows one to ignore the political issues, in other words what populists are actually saying and why. This, at least, is compatible with the prevailing view that populist positions are so obviously irrational that there is no point in bothering to discuss them anyway. However, this is nothing but the abjuration of the pluralist claim bandied about to characterise populism in the first place. In particular, it enables avoidance of basic questions of redistribution and scarcity, such as that of the losers of cosmopolitan humanitarianism: a question that the (German) middle class no longer likes to talk about, because it hardly comes into contact with them.

Disregarding the substance of populism and focusing exclusively on its exclusionary rhetoric may succeed in protecting the definition of populism from everyday polemic, however it also allows one to ignore the political issues, in other words what populists are actually saying and why. This, at least, is compatible with the prevailing view that populist positions are so obviously irrational that there is no point in bothering to discuss them anyway. However, this is nothing but the abjuration of the pluralist claim bandied about to characterise populism in the first place. In particular, it enables avoidance of basic questions of redistribution and scarcity, such as that of the losers of cosmopolitan humanitarianism: a question that the (German) middle class no longer likes to talk about, because it hardly comes into contact with them. When Burne-Jones painted his Briar Rose cycle, grown women who had too much to say and to do were being forcibly put to bed. They were diagnosed as hysterics, depressives and neurasthenics, whose delicate nerves were no match for their mental gymnastics, and given a prescription of hardcore rest. Many of these women were insomniac. Some had eating disorders; others were suicidal. To a woman (almost) they balked at the societal restrictions that corralled them into being mothers and homemakers and disallowed anything else. Nervous conditions, sleeplessness, self-starvation (that is, disappearing before you are made to disappear), this was their protest.

When Burne-Jones painted his Briar Rose cycle, grown women who had too much to say and to do were being forcibly put to bed. They were diagnosed as hysterics, depressives and neurasthenics, whose delicate nerves were no match for their mental gymnastics, and given a prescription of hardcore rest. Many of these women were insomniac. Some had eating disorders; others were suicidal. To a woman (almost) they balked at the societal restrictions that corralled them into being mothers and homemakers and disallowed anything else. Nervous conditions, sleeplessness, self-starvation (that is, disappearing before you are made to disappear), this was their protest. There were just eight ingredients: two proteins, three buffering agents, two types of fat molecule and some chemical energy. But that was enough to create a flotilla of bouncing, pulsating blobs — rudimentary cell-like structures with some of the machinery necessary to divide on their own. To biophysicist Petra Schwille, the dancing creations in her lab represent an important step towards building a synthetic cell from the bottom up, something she has been working towards for the past ten years, most recently at the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry in Martinsried, Germany. “I have always been fascinated by this question, ‘What distinguishes life from non-living matter?’” she says. The challenge, according to Schwille, is to determine which components are needed to make a living system. In her perfect synthetic cell, she’d know every single factor that makes it tick.

There were just eight ingredients: two proteins, three buffering agents, two types of fat molecule and some chemical energy. But that was enough to create a flotilla of bouncing, pulsating blobs — rudimentary cell-like structures with some of the machinery necessary to divide on their own. To biophysicist Petra Schwille, the dancing creations in her lab represent an important step towards building a synthetic cell from the bottom up, something she has been working towards for the past ten years, most recently at the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry in Martinsried, Germany. “I have always been fascinated by this question, ‘What distinguishes life from non-living matter?’” she says. The challenge, according to Schwille, is to determine which components are needed to make a living system. In her perfect synthetic cell, she’d know every single factor that makes it tick.