The One Day

We were behind on the job

so waited out the rain in the pickup.

Because the backhoe would mire

he shouldered the four-foot pipe joints

and brought them to us in the ditch.

The red mud clutched and tugged at his boots

and Bill laughed at his “Swan Lake”

as he fought through, lurching and staggering

when the mud would suddenly let go.

But he kept them coming, lugging the red joints

to us and then slogging back for another

while we slid on the gasket and fit the pipes together.

You can see how, pushing like that, he wound up,

two years later, with the tiny plastic piping of IVs

feeding into both arms and the three drainage tubes

snaking from under the patch on his chest.

His skin was a shade away from being same as the sheet

when I saw him in the ICU,

and he couldn’t have lifted the drinking straw

on the bedside tray.

But that one day he brought two hundred yards of pipe

and even the red earth couldn’t stop him.

by Michael Chitwood

from My Laureate’s Lasso

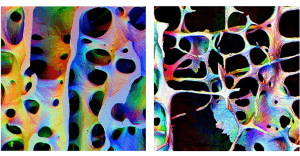

Simplicity, simplicity, simplicity!” Henry David Thoreau exhorted in his 1854 memoir Walden, in which he extolled the virtues of a “Spartan-like” life. Saint Thomas Aquinas preached that simplicity brings one closer to God. Isaac Newton believed it leads to truth. The process of simplification, we’re told, can illuminate beauty, strip away needless clutter and stress, and help us focus on what really matters. It can also be a sign of aging. Youthful health and vigor depend, in many ways, on complexity. Bones get strength from elaborate scaffolds of connective tissue. Mental acuity arises from interconnected webs of neurons. Even seemingly simple bodily functions like heartbeat rely on interacting networks of metabolic controls, signaling pathways, genetic switches, and circadian rhythms. As our bodies age, these anatomic structures and physiologic processes lose complexity, making them less resilient and ultimately leading to frailty and disease.

Simplicity, simplicity, simplicity!” Henry David Thoreau exhorted in his 1854 memoir Walden, in which he extolled the virtues of a “Spartan-like” life. Saint Thomas Aquinas preached that simplicity brings one closer to God. Isaac Newton believed it leads to truth. The process of simplification, we’re told, can illuminate beauty, strip away needless clutter and stress, and help us focus on what really matters. It can also be a sign of aging. Youthful health and vigor depend, in many ways, on complexity. Bones get strength from elaborate scaffolds of connective tissue. Mental acuity arises from interconnected webs of neurons. Even seemingly simple bodily functions like heartbeat rely on interacting networks of metabolic controls, signaling pathways, genetic switches, and circadian rhythms. As our bodies age, these anatomic structures and physiologic processes lose complexity, making them less resilient and ultimately leading to frailty and disease. Today, cars with semi-autonomous features are already on the road. Automatic parallel parking has been commercially available since 2003. Cadillac allows drivers to go hands-free on pre-approved routes. Some B.M.W. S.U.V.s can be equipped with, for an additional seventeen-hundred dollars, a system that takes over during “monotonous traffic situations”—more colloquially known as traffic jams. But a mass-produced driverless car remains elusive. In 2013, the U.S. Department of Transportation’s National Highway Traffic Safety Administration published a sliding scale that ranked cars on their level of autonomy. The vast majority of vehicles are still at level zero. A car at level four would be highly autonomous in basic situations, like highways, but would need a human operator. Cars at level five would drive as well as or better than humans, smoothly adapting to rapid changes in their environments, like swerving cars or stray pedestrians. This would require the vehicles to make value judgments, including in versions of a classic philosophy thought experiment called the trolley problem: if a car detects a sudden obstacle—say, a jackknifed truck—should it hit the truck and kill its own driver, or should it swerve onto a crowded sidewalk and kill pedestrians? A human driver might react randomly (if she has time to react at all), but the response of an autonomous vehicle would have to be programmed ahead of time. What should we tell the car to do?

Today, cars with semi-autonomous features are already on the road. Automatic parallel parking has been commercially available since 2003. Cadillac allows drivers to go hands-free on pre-approved routes. Some B.M.W. S.U.V.s can be equipped with, for an additional seventeen-hundred dollars, a system that takes over during “monotonous traffic situations”—more colloquially known as traffic jams. But a mass-produced driverless car remains elusive. In 2013, the U.S. Department of Transportation’s National Highway Traffic Safety Administration published a sliding scale that ranked cars on their level of autonomy. The vast majority of vehicles are still at level zero. A car at level four would be highly autonomous in basic situations, like highways, but would need a human operator. Cars at level five would drive as well as or better than humans, smoothly adapting to rapid changes in their environments, like swerving cars or stray pedestrians. This would require the vehicles to make value judgments, including in versions of a classic philosophy thought experiment called the trolley problem: if a car detects a sudden obstacle—say, a jackknifed truck—should it hit the truck and kill its own driver, or should it swerve onto a crowded sidewalk and kill pedestrians? A human driver might react randomly (if she has time to react at all), but the response of an autonomous vehicle would have to be programmed ahead of time. What should we tell the car to do? Last week, as world leaders and business elites arrived in Davos for the

Last week, as world leaders and business elites arrived in Davos for the  A new report from the

A new report from the  In 1966, Robert “Bob” Taylor, an employee at the U.S. government’s Advanced Research Projects Agency, had an insight that led to the creation of the internet: “[Bob Taylor’s] most enduring legacy, however, was … a leap of intuition that tied together everything else he had done. This was the ARPANET, the precursor of today’s Internet.

In 1966, Robert “Bob” Taylor, an employee at the U.S. government’s Advanced Research Projects Agency, had an insight that led to the creation of the internet: “[Bob Taylor’s] most enduring legacy, however, was … a leap of intuition that tied together everything else he had done. This was the ARPANET, the precursor of today’s Internet. Donald Trump has been hot for Venezuela for some time now. In the summer of 2017, Trump, citing George H.W. Bush’s 1989–90 invasion of Panama as a positive precedent, repeatedly

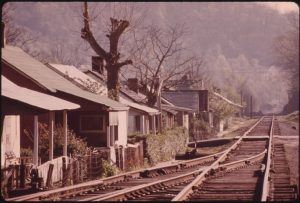

Donald Trump has been hot for Venezuela for some time now. In the summer of 2017, Trump, citing George H.W. Bush’s 1989–90 invasion of Panama as a positive precedent, repeatedly  Political veterans such as Pelosi and Israel think that the cornerstones of the emerging left platform—housing as a human right, criminal justice reform, Medicare for all, tuition-free public colleges and trade schools, a federal jobs guarantee, abolition of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and for-profit prisons, campaign finance reform, and a Green New Deal—might perform well in urban centers but not so much elsewhere. Appalachia has become symbolic of the forces that gave us Trump. After all, his pandering to white racial anxiety did find purchase here. His fantasies to make America great again center on our dying coal industry. And the region’s conservative voters, who have been profiled endlessly, have been a reliable stand-in for all Trump voters, absorbing the outrage of progressive readers. But what Pelosi and Israel see as common sense and pragmatism can also be interpreted as tired oversimplifications and a failure of imagination.

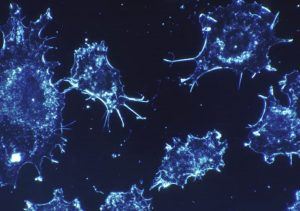

Political veterans such as Pelosi and Israel think that the cornerstones of the emerging left platform—housing as a human right, criminal justice reform, Medicare for all, tuition-free public colleges and trade schools, a federal jobs guarantee, abolition of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and for-profit prisons, campaign finance reform, and a Green New Deal—might perform well in urban centers but not so much elsewhere. Appalachia has become symbolic of the forces that gave us Trump. After all, his pandering to white racial anxiety did find purchase here. His fantasies to make America great again center on our dying coal industry. And the region’s conservative voters, who have been profiled endlessly, have been a reliable stand-in for all Trump voters, absorbing the outrage of progressive readers. But what Pelosi and Israel see as common sense and pragmatism can also be interpreted as tired oversimplifications and a failure of imagination. The potentially game-changing anti-cancer drug is based on SoAP technology, which belongs to the phage display group of technologies. It involves the introduction of DNA coding for a protein, such as an antibody, into a bacteriophage – a virus that infects bacteria. That protein is then displayed on the surface of the phage. Researchers can use these protein-displaying phages to screen for interactions with other proteins, DNA sequences and small molecules.

The potentially game-changing anti-cancer drug is based on SoAP technology, which belongs to the phage display group of technologies. It involves the introduction of DNA coding for a protein, such as an antibody, into a bacteriophage – a virus that infects bacteria. That protein is then displayed on the surface of the phage. Researchers can use these protein-displaying phages to screen for interactions with other proteins, DNA sequences and small molecules. With support from

With support from

How do you recommend an experience you never want to have again? How does a film critic say, for instance, that Requiem for a Dream is a must-watch, when it’s infused with such ugliness and despair? When a piece of art is unapologetically dark and unpleasant but of objectively excellent quality, finding a way to push audiences toward it is a challenge.

How do you recommend an experience you never want to have again? How does a film critic say, for instance, that Requiem for a Dream is a must-watch, when it’s infused with such ugliness and despair? When a piece of art is unapologetically dark and unpleasant but of objectively excellent quality, finding a way to push audiences toward it is a challenge. The best parts of “Art and Morality” (1925) are not about art or morality but – via an extraordinary speculative detour into the lives of ancient Egyptians – about how the “Kodak” habit of photographing oneself all the time has fundamentally changed our sense of ourselves: a prophetic diagnosis of a defining malaise of the iPhone era. In an editorial note to “Introduction to Pictures” the scholar James T Boulton rightly points out that the essay “does not once refer to pictures”. This tendency to stray from stated intentions was best expressed by Lawrence himself on 5 September 1914. “Out of sheer rage I’ve begun my book about Thomas Hardy. It will be about anything but Thomas Hardy I am afraid – queer stuff – but not bad.”

The best parts of “Art and Morality” (1925) are not about art or morality but – via an extraordinary speculative detour into the lives of ancient Egyptians – about how the “Kodak” habit of photographing oneself all the time has fundamentally changed our sense of ourselves: a prophetic diagnosis of a defining malaise of the iPhone era. In an editorial note to “Introduction to Pictures” the scholar James T Boulton rightly points out that the essay “does not once refer to pictures”. This tendency to stray from stated intentions was best expressed by Lawrence himself on 5 September 1914. “Out of sheer rage I’ve begun my book about Thomas Hardy. It will be about anything but Thomas Hardy I am afraid – queer stuff – but not bad.” The history of Islam’s relation to science has largely been one of harmony. It offers no real parallel to the occasional bouts of suspicion toward science that the Christian world experienced. Today, many Muslims can be found in the fields of medicine and engineering. Even the ultraconservative Muslims who long for a return to the ethical norms of the seventh century see no need to abandon cell phones to do so, and even the most extreme of Islamic extremists envies the high-tech oil-extraction techniques and the weaponry of the West. Muslims, both conservative and liberal, issue fatwas (legal opinions) over the Internet without any hesitation over the technology they employ and with no fear that it may be haram (prohibited).

The history of Islam’s relation to science has largely been one of harmony. It offers no real parallel to the occasional bouts of suspicion toward science that the Christian world experienced. Today, many Muslims can be found in the fields of medicine and engineering. Even the ultraconservative Muslims who long for a return to the ethical norms of the seventh century see no need to abandon cell phones to do so, and even the most extreme of Islamic extremists envies the high-tech oil-extraction techniques and the weaponry of the West. Muslims, both conservative and liberal, issue fatwas (legal opinions) over the Internet without any hesitation over the technology they employ and with no fear that it may be haram (prohibited). In 2014 John Cryan, a professor at University College Cork in Ireland, attended a meeting in California about Alzheimer’s disease. He wasn’t an expert on dementia. Instead, he studied the microbiome, the trillions of microbes inside the healthy human body. Dr. Cryan and other scientists were beginning to find hints that these microbes could influence the brain and behavior. Perhaps, he told the scientific gathering, the microbiome has a role in the development of Alzheimer’s disease. The idea was not well received. “I’ve never given a talk to so many people who didn’t believe what I was saying,” Dr. Cryan recalled. A lot has changed since then: Research continues to turn up remarkable links between the microbiome and the brain. Scientists are finding evidence that microbiome may play a role not just in Alzheimer’s disease, but Parkinson’s disease, depression, schizophrenia, autism and other conditions.

In 2014 John Cryan, a professor at University College Cork in Ireland, attended a meeting in California about Alzheimer’s disease. He wasn’t an expert on dementia. Instead, he studied the microbiome, the trillions of microbes inside the healthy human body. Dr. Cryan and other scientists were beginning to find hints that these microbes could influence the brain and behavior. Perhaps, he told the scientific gathering, the microbiome has a role in the development of Alzheimer’s disease. The idea was not well received. “I’ve never given a talk to so many people who didn’t believe what I was saying,” Dr. Cryan recalled. A lot has changed since then: Research continues to turn up remarkable links between the microbiome and the brain. Scientists are finding evidence that microbiome may play a role not just in Alzheimer’s disease, but Parkinson’s disease, depression, schizophrenia, autism and other conditions.