A Glittering

One mourner says if I can just get through this year as if salvation comes in January.

Slow dance of suicides into the earth:

I see no proof there is anything else. I keep my obituary current, but believe that good times are right around the corner

Una grande scultura posse rotolare giù per una collina senza rompersi, Michelangelo is believed to have said (though he never did): To determine the essential parts of a sculpture, roll it down a hill. The inessential parts will break off.

That hill, graveyard of the inessential, is discovered by the hopeless and mistaken for the world just before they mistake themselves for David’s white arms.

They are wrong. But to assume oneself essential is also wrong: a conundrum.

To be neither essential nor inessential—not to exist except as the object of someone’s belief, like those good times lying right around the corner—is the only possibility.

Nothing, nobody matters.

And yet the world is full of love . . .

by Arah Manguso

From Blackbird Magazine, Spring 2005

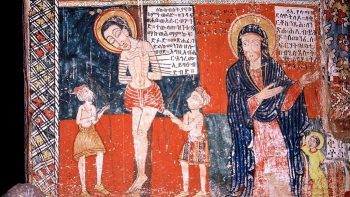

In the 14th century, the Black Death swept across Europe, Asia, and North Africa, killing up to 50% of the population in some cities. But archaeologists and historians have assumed that the plague bacterium Yersinia pestis, carried by fleas infesting rodents, didn’t make it across the Sahara Desert. Medieval sub-Saharan Africa’s few written records make no mention of plague, and the region lacks mass graves resembling the “plague pits” of Europe. Nor did European explorers of the 15th and 16th centuries record any sign of the disease, even though outbreaks continued to beset Europe. Now, some researchers point to new evidence from archaeology, history, and genetics to argue that the Black Death likely did sow devastation in medieval sub-Saharan Africa. “It’s entirely possible that [plague] would have headed south,” says Anne Stone, an anthropological geneticist who studies ancient pathogens at Arizona State University (ASU) in Tempe. If proved, the presence of plague would put renewed attention on the medieval trade routes that linked sub-Saharan Africa to other continents. But Stone and others caution that the evidence so far is circumstantial; researchers need ancient DNA from Africa to clinch their case. The new finds, to be presented this week at a conference at the University of Paris, may spur more scientists to search for it.

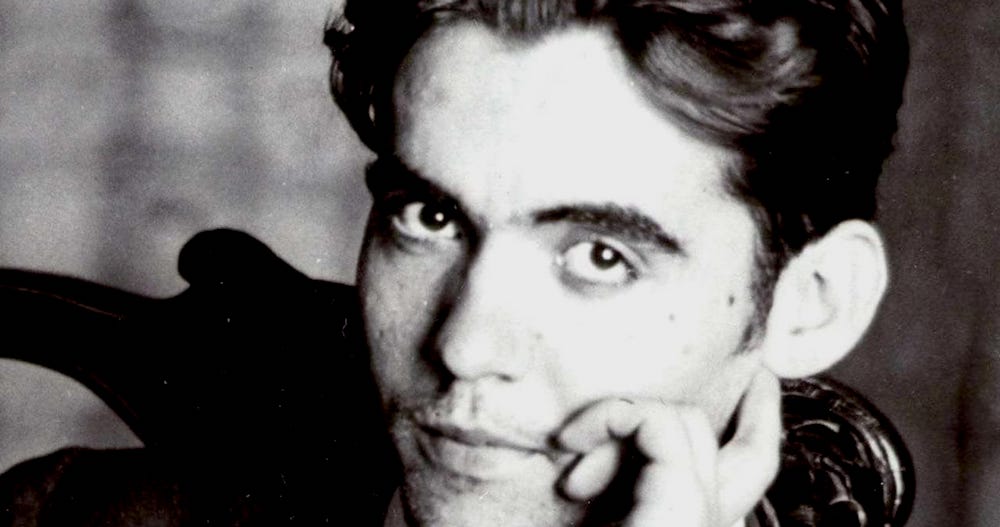

In the 14th century, the Black Death swept across Europe, Asia, and North Africa, killing up to 50% of the population in some cities. But archaeologists and historians have assumed that the plague bacterium Yersinia pestis, carried by fleas infesting rodents, didn’t make it across the Sahara Desert. Medieval sub-Saharan Africa’s few written records make no mention of plague, and the region lacks mass graves resembling the “plague pits” of Europe. Nor did European explorers of the 15th and 16th centuries record any sign of the disease, even though outbreaks continued to beset Europe. Now, some researchers point to new evidence from archaeology, history, and genetics to argue that the Black Death likely did sow devastation in medieval sub-Saharan Africa. “It’s entirely possible that [plague] would have headed south,” says Anne Stone, an anthropological geneticist who studies ancient pathogens at Arizona State University (ASU) in Tempe. If proved, the presence of plague would put renewed attention on the medieval trade routes that linked sub-Saharan Africa to other continents. But Stone and others caution that the evidence so far is circumstantial; researchers need ancient DNA from Africa to clinch their case. The new finds, to be presented this week at a conference at the University of Paris, may spur more scientists to search for it. Before dawn on August 17th, 1936, a man dressed in white pajamas and a blazer stepped out of a car onto the dirt road connecting the towns of Víznar and Alfacar in the foothills outside Granada, Spain. He had thick, arching eyebrows, a widow’s peak sharpened by a tar-black receding hairline, and a slight gut that looked good on his 38-year-old frame.

Before dawn on August 17th, 1936, a man dressed in white pajamas and a blazer stepped out of a car onto the dirt road connecting the towns of Víznar and Alfacar in the foothills outside Granada, Spain. He had thick, arching eyebrows, a widow’s peak sharpened by a tar-black receding hairline, and a slight gut that looked good on his 38-year-old frame. In

In It should be “okay” for Americans who want their country to have a close alliance with a foreign power to form political organizations that advance their views. The problem with AIPAC is not that it pushes American lawmakers to show deference to the interests of another country. The problem is that it pushes them to

It should be “okay” for Americans who want their country to have a close alliance with a foreign power to form political organizations that advance their views. The problem with AIPAC is not that it pushes American lawmakers to show deference to the interests of another country. The problem is that it pushes them to C

C The discovery of Newton’s alchemical manuscripts – containing no fewer than a million words, some of the pages mutilated by the acids used during his quest for the philosopher’s stone – led to a flurry of scholarly activity. This culminated in the 1980s in the work of Richard Westfall, still Newton’s greatest biographer, and Betty Jo Teeter Dobbs. In a spectacular rejection of Butterfield’s dismissiveness, they argued that alchemy underpinned Newton’s whole world-view. Newton’s belief in transmutation, Dobbs claimed, was akin to a religious quest, with the ‘philosophic mercury’, believed to be ableto break down metals into their constituent parts, acting as a spirit mediating between the physical and divine realms. Westfall suggested that it was assumptions born in Newton’s alchemical researches about invisible forces acting at a distance that allowed him to develop his greatest theory: that of universal gravitation, which he announced to the world in his Principia of 1687.

The discovery of Newton’s alchemical manuscripts – containing no fewer than a million words, some of the pages mutilated by the acids used during his quest for the philosopher’s stone – led to a flurry of scholarly activity. This culminated in the 1980s in the work of Richard Westfall, still Newton’s greatest biographer, and Betty Jo Teeter Dobbs. In a spectacular rejection of Butterfield’s dismissiveness, they argued that alchemy underpinned Newton’s whole world-view. Newton’s belief in transmutation, Dobbs claimed, was akin to a religious quest, with the ‘philosophic mercury’, believed to be ableto break down metals into their constituent parts, acting as a spirit mediating between the physical and divine realms. Westfall suggested that it was assumptions born in Newton’s alchemical researches about invisible forces acting at a distance that allowed him to develop his greatest theory: that of universal gravitation, which he announced to the world in his Principia of 1687. “Painting,” painted by Joan Miró in 1933, in Barcelona, is a composition of black, red, and white blobby shapes and linear glyphs on a ground of bleeding and blending greens and browns. It hangs in “Joan Miró: Birth of the World,” an enchanting show at the Museum of Modern Art that draws on the museum’s immense holdings of Miró’s work, along with a few loans. “Painting” is a bit sombre, for him, but it has the ineffably friendly air of nearly all his art: adventurous but easy-looking, an eager gift to vision and imagination. It invokes a word inevitably applied to Miró: “poetic,” redolent of the magic, residual in us, of childhood rhymes, with or without figurative elements. Never unsettling in the ways of, say, Matisse or, for heaven’s sake, Picasso, Miró is a modernist for everybody. (He died in 1983, at the age of ninety.) This has given him a peculiar trajectory in the modern-art canon: he was considered majestic at points in the past, in ways that feel somewhat flimsy now. Looking at “Painting” helps me think about the art world’s shifting estimation of the “international Catalan,” as Miró termed himself. It stirs a personal memory.

“Painting,” painted by Joan Miró in 1933, in Barcelona, is a composition of black, red, and white blobby shapes and linear glyphs on a ground of bleeding and blending greens and browns. It hangs in “Joan Miró: Birth of the World,” an enchanting show at the Museum of Modern Art that draws on the museum’s immense holdings of Miró’s work, along with a few loans. “Painting” is a bit sombre, for him, but it has the ineffably friendly air of nearly all his art: adventurous but easy-looking, an eager gift to vision and imagination. It invokes a word inevitably applied to Miró: “poetic,” redolent of the magic, residual in us, of childhood rhymes, with or without figurative elements. Never unsettling in the ways of, say, Matisse or, for heaven’s sake, Picasso, Miró is a modernist for everybody. (He died in 1983, at the age of ninety.) This has given him a peculiar trajectory in the modern-art canon: he was considered majestic at points in the past, in ways that feel somewhat flimsy now. Looking at “Painting” helps me think about the art world’s shifting estimation of the “international Catalan,” as Miró termed himself. It stirs a personal memory. What do little girls like? As a child, I preferred Lego to dolls and, if asked what I wanted to be when I grew up, was apt to reply: a detective, or a reporter. My parents were scientists, so our household was in some ways less obviously gendered than most (though I went on to do an arts degree, two of my sisters read biochemistry and maths at university). Nevertheless, it was always in the air: the way girls should be, and therefore are. By the time I was a teenager, I’d learned to feel quite odd about certain of my tastes and aptitudes. I’d also internalised various stereotypes. I took great pride, for instance, in my map-reading – not because map-reading is intrinsically difficult, but because some small part of me accepted that women are not supposed to be any good at it.

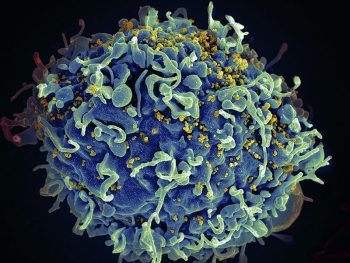

What do little girls like? As a child, I preferred Lego to dolls and, if asked what I wanted to be when I grew up, was apt to reply: a detective, or a reporter. My parents were scientists, so our household was in some ways less obviously gendered than most (though I went on to do an arts degree, two of my sisters read biochemistry and maths at university). Nevertheless, it was always in the air: the way girls should be, and therefore are. By the time I was a teenager, I’d learned to feel quite odd about certain of my tastes and aptitudes. I’d also internalised various stereotypes. I took great pride, for instance, in my map-reading – not because map-reading is intrinsically difficult, but because some small part of me accepted that women are not supposed to be any good at it. A person with HIV seems to be free of the virus after receiving a stem-cell transplant that replaced their white blood cells with HIV-resistant versions. The patient is only the second person ever reported to have been cleared of the virus using this method. But researchers warn that it is too early to say that they have been cured. The patient — whose identity hasn’t been disclosed — was able to stop taking antiretroviral drugs, with no sign of the virus returning 18 months later. The stem-cell technique was

A person with HIV seems to be free of the virus after receiving a stem-cell transplant that replaced their white blood cells with HIV-resistant versions. The patient is only the second person ever reported to have been cleared of the virus using this method. But researchers warn that it is too early to say that they have been cured. The patient — whose identity hasn’t been disclosed — was able to stop taking antiretroviral drugs, with no sign of the virus returning 18 months later. The stem-cell technique was  Imagine you are on a bus ride to an unknown destination. The road is little more than a dirt track, littered with potholes, and you are constantly bounced around in your seat. There is no air conditioning. Sweat is dripping down your back and you are starting to smell. The same is true of your fellow travelers. Some of them have brought livestock and other animals on board. Kids are screaming; the bathrooms are blocked and overflowing. It is clear that no one on the bus has any idea where you are going, and only the haziest idea of where you are coming from. Nevertheless, all around you people are making up stories—ungrounded in logic and untethered to evidence—about where they are going to alight and what their prospects will be once they get there.

Imagine you are on a bus ride to an unknown destination. The road is little more than a dirt track, littered with potholes, and you are constantly bounced around in your seat. There is no air conditioning. Sweat is dripping down your back and you are starting to smell. The same is true of your fellow travelers. Some of them have brought livestock and other animals on board. Kids are screaming; the bathrooms are blocked and overflowing. It is clear that no one on the bus has any idea where you are going, and only the haziest idea of where you are coming from. Nevertheless, all around you people are making up stories—ungrounded in logic and untethered to evidence—about where they are going to alight and what their prospects will be once they get there. Quantum mechanics is our best theory of how reality works at a fundamental level, yet physicists still can’t agree on what the theory actually says. At the heart of the puzzle is the “measurement problem”: what actually happens when we observe a quantum system, and why do we apparently need separate rules when it happens? David Albert is one of the leading figures in the foundations of quantum mechanics today, and we discuss the measurement problem and why it’s so puzzling. Then we dive into the Many-Worlds version of quantum mechanics, which is my favorite (as I explain in my forthcoming book

Quantum mechanics is our best theory of how reality works at a fundamental level, yet physicists still can’t agree on what the theory actually says. At the heart of the puzzle is the “measurement problem”: what actually happens when we observe a quantum system, and why do we apparently need separate rules when it happens? David Albert is one of the leading figures in the foundations of quantum mechanics today, and we discuss the measurement problem and why it’s so puzzling. Then we dive into the Many-Worlds version of quantum mechanics, which is my favorite (as I explain in my forthcoming book  Citizens of

Citizens of  But beyond the pleasure of Dreyer’s prose and authorial tone, I think there is something else at play with the popularity of his book. To put it as simply as possible, the man cares, and we need people who care right now. Dreyer’s English is, beyond a freakin’ style guide, the document of a serious person’s working life. At sixty, Dreyer is at the top of his game and profession, an honorable profession he has worked diligently at for more than three decades. To write a book is to care deeply and in a sustained way about something; to copyedit a book is to care deeply and in a sustained way about someone else’s deep and sustained caring. And to have copyedited books for one’s adult life is to have spent one’s adult life caring about other people’s words and the English language. As he writes in the introduction:

But beyond the pleasure of Dreyer’s prose and authorial tone, I think there is something else at play with the popularity of his book. To put it as simply as possible, the man cares, and we need people who care right now. Dreyer’s English is, beyond a freakin’ style guide, the document of a serious person’s working life. At sixty, Dreyer is at the top of his game and profession, an honorable profession he has worked diligently at for more than three decades. To write a book is to care deeply and in a sustained way about something; to copyedit a book is to care deeply and in a sustained way about someone else’s deep and sustained caring. And to have copyedited books for one’s adult life is to have spent one’s adult life caring about other people’s words and the English language. As he writes in the introduction: GASPAR NOÉ’S CLIMAX is an encyclopedia of ways in which the human body can bend and break, a sailor’s knot guide of the contortions possible with four limbs, a trunk, and a head, skulls seemingly empty here of thoughts other than sex and death. Set in an isolated school somewhere outside of Paris where a troupe of hip-hop dancers have assembled for intensive rehearsals before an impending American tour, the movie unravels in something like real-time as, cutting loose at the end of a day’s work, they dip into a punchbowl of sangria before discovering that one of their group has spiked it with LSD, precipitating a collective freak-out.

GASPAR NOÉ’S CLIMAX is an encyclopedia of ways in which the human body can bend and break, a sailor’s knot guide of the contortions possible with four limbs, a trunk, and a head, skulls seemingly empty here of thoughts other than sex and death. Set in an isolated school somewhere outside of Paris where a troupe of hip-hop dancers have assembled for intensive rehearsals before an impending American tour, the movie unravels in something like real-time as, cutting loose at the end of a day’s work, they dip into a punchbowl of sangria before discovering that one of their group has spiked it with LSD, precipitating a collective freak-out.