Emily Polk in Emergence:

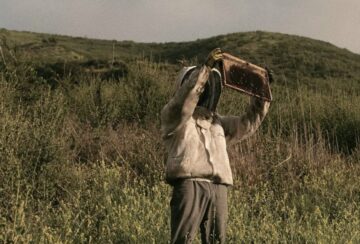

I have loved bees my entire life, though my love for beekeepers started when I was writing a story for the Boston Globe about the dangers of mites to bee colonies in North America. I drove out to Hudson, a conservative town in rural New Hampshire, to meet leaders of the New Hampshire Beekeepers Association. I arrived just in time to watch a couple of senior bearded men in flannel shirts and Carhartt pants transport crates of bees into new hives. I was completely entranced by their delicacy and elegance. They seemed to be dancing. I wrote of one of the beekeepers, “He moves in a graceful rhythm … shaking the three-pound crate of bees into the hive, careful not to crush the queen, careful to make sure she has enough bees to tend to her, careful not to disturb or alarm them as he tenderly puts the frames back into the hive. And he does not get stung.” I was not expecting to find old men dancing with the grace of ballerinas under pine trees with a tenderness for the bees I wouldn’t have been able to imagine had I not witnessed it myself. This moment marked the beginning of my interest in what bees could teach us.

I have loved bees my entire life, though my love for beekeepers started when I was writing a story for the Boston Globe about the dangers of mites to bee colonies in North America. I drove out to Hudson, a conservative town in rural New Hampshire, to meet leaders of the New Hampshire Beekeepers Association. I arrived just in time to watch a couple of senior bearded men in flannel shirts and Carhartt pants transport crates of bees into new hives. I was completely entranced by their delicacy and elegance. They seemed to be dancing. I wrote of one of the beekeepers, “He moves in a graceful rhythm … shaking the three-pound crate of bees into the hive, careful not to crush the queen, careful to make sure she has enough bees to tend to her, careful not to disturb or alarm them as he tenderly puts the frames back into the hive. And he does not get stung.” I was not expecting to find old men dancing with the grace of ballerinas under pine trees with a tenderness for the bees I wouldn’t have been able to imagine had I not witnessed it myself. This moment marked the beginning of my interest in what bees could teach us.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The question that leaders of research universities must grapple with is this: How can we preserve and enhance what is uniquely valuable about the research university? To do that, we must begin by defining what is “uniquely valuable”—that is, what research universities do better than any other existing institution, and without which society would suffer badly. I take those uniquely valuable attributes to be: (a) the creation of highly well-trained experts; (b) path-breaking knowledge creation; and, crucially, though often ignored or even denigrated, (c) knowledge preservation and transmission.

The question that leaders of research universities must grapple with is this: How can we preserve and enhance what is uniquely valuable about the research university? To do that, we must begin by defining what is “uniquely valuable”—that is, what research universities do better than any other existing institution, and without which society would suffer badly. I take those uniquely valuable attributes to be: (a) the creation of highly well-trained experts; (b) path-breaking knowledge creation; and, crucially, though often ignored or even denigrated, (c) knowledge preservation and transmission. When Édouard Manet exhibited Olympia in the Salon of 1865, it unleashed a firestorm. Viewers were shocked by the subject matter—the sheer nakedness of the sitter—and by his formal treatment of the subject: critics lamented the lack of finish, the sharp contrast between light and dark, and, above all, the starkness of the model’s outward look at the viewer. For critics at the time, Manet’s shocking way with form went hand in hand with a sense of moral outrage, around gender and class. Olympia subtly but powerfully broke all the unspoken rules about the nude in painting and set the standard for a new form of revolutionary modern art.

When Édouard Manet exhibited Olympia in the Salon of 1865, it unleashed a firestorm. Viewers were shocked by the subject matter—the sheer nakedness of the sitter—and by his formal treatment of the subject: critics lamented the lack of finish, the sharp contrast between light and dark, and, above all, the starkness of the model’s outward look at the viewer. For critics at the time, Manet’s shocking way with form went hand in hand with a sense of moral outrage, around gender and class. Olympia subtly but powerfully broke all the unspoken rules about the nude in painting and set the standard for a new form of revolutionary modern art. If you are a leading woman in a Pedro Almodóvar film, your life will not be frictionless. You will have a terminal illness. Or if you don’t have one, you will be grieving the one that someone very close to you has. You will be a single mother or mother-to-be. You will have very intimate female friendships, but you won’t always be faithful, or act selflessly. You will work a creative career, such as writing or acting or photographing products for advertisements. You won’t care too much about traditional values even though your Catholic family or community does. You will smoke cigarettes and pop pills when you’re stressed. You might have paid a pretty penny for your breasts, or have been naturally endowed. You will be unconventionally, or maybe conventionally, beautiful, and always expressive. You will be middle-aged. You will have a romantic Castilian accent. You might be Penélope Cruz.

If you are a leading woman in a Pedro Almodóvar film, your life will not be frictionless. You will have a terminal illness. Or if you don’t have one, you will be grieving the one that someone very close to you has. You will be a single mother or mother-to-be. You will have very intimate female friendships, but you won’t always be faithful, or act selflessly. You will work a creative career, such as writing or acting or photographing products for advertisements. You won’t care too much about traditional values even though your Catholic family or community does. You will smoke cigarettes and pop pills when you’re stressed. You might have paid a pretty penny for your breasts, or have been naturally endowed. You will be unconventionally, or maybe conventionally, beautiful, and always expressive. You will be middle-aged. You will have a romantic Castilian accent. You might be Penélope Cruz. About two millennia ago, the Greek physicians Hippocrates and Galen suggested that melancholia — depression brought on by an excess of “black bile” in the body — contributed to cancer. Since then, scores of researchers have investigated the association between cancer and the mind, with some going as far as to suggest that some people have a cancer-prone or “Type C” personality.

About two millennia ago, the Greek physicians Hippocrates and Galen suggested that melancholia — depression brought on by an excess of “black bile” in the body — contributed to cancer. Since then, scores of researchers have investigated the association between cancer and the mind, with some going as far as to suggest that some people have a cancer-prone or “Type C” personality. O

O Dr. Garcia is part of a leading lab, run by toxicologist Matthew Campen, that is studying how tiny particles known as microplastics accumulate in our bodies. The researchers’

Dr. Garcia is part of a leading lab, run by toxicologist Matthew Campen, that is studying how tiny particles known as microplastics accumulate in our bodies. The researchers’  Trump and his trade advisers insist that the rules governing global commerce put the United States at a distinct disadvantage. But mainstream economists—whose views Trump and his advisers disdain—say the president has a warped idea of world trade, especially a preoccupation with trade deficits, which they say do nothing to impede growth.

Trump and his trade advisers insist that the rules governing global commerce put the United States at a distinct disadvantage. But mainstream economists—whose views Trump and his advisers disdain—say the president has a warped idea of world trade, especially a preoccupation with trade deficits, which they say do nothing to impede growth. ‘W

‘W I

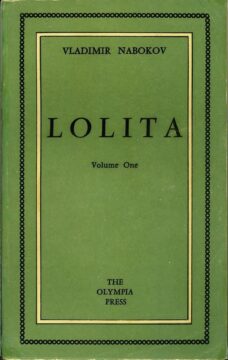

I At 70, Vladimir Nabokov’s most famous book, Lolita, is decidedly problematic. It is, after all, a novel narrated by a pedophile, kidnapper, and rapist (also, lest we forget, murderer) who tells his story from prison, who relates his crimes with a pyrotechnic verbal exhilaration that is tantamount to glee, who seduces each reader into complicity simply through the act of reading: to read the novel to the end is to have succumbed to Humbert Humbert’s insidious, sullying charms. Framed by the banal platitudes of John Ray Jr., the fictional psychologist whose foreword introduces the account (“‘Lolita’ should make all of us—parents, social workers, educators—apply ourselves with still greater vigilance and vision to the task of bringing up a better generation in a safer world”), Humbert’s exuberant voice seduces the reader, even as so many of the novel’s characters are foolishly, sometimes fatally, seduced. What are we doing, when we read this book with such pleasure? What was Nabokov doing, in writing this unsettling novel?

At 70, Vladimir Nabokov’s most famous book, Lolita, is decidedly problematic. It is, after all, a novel narrated by a pedophile, kidnapper, and rapist (also, lest we forget, murderer) who tells his story from prison, who relates his crimes with a pyrotechnic verbal exhilaration that is tantamount to glee, who seduces each reader into complicity simply through the act of reading: to read the novel to the end is to have succumbed to Humbert Humbert’s insidious, sullying charms. Framed by the banal platitudes of John Ray Jr., the fictional psychologist whose foreword introduces the account (“‘Lolita’ should make all of us—parents, social workers, educators—apply ourselves with still greater vigilance and vision to the task of bringing up a better generation in a safer world”), Humbert’s exuberant voice seduces the reader, even as so many of the novel’s characters are foolishly, sometimes fatally, seduced. What are we doing, when we read this book with such pleasure? What was Nabokov doing, in writing this unsettling novel? They say a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush, but for computer scientists, two birds in a hole are better still. That’s because those cohabiting birds are the protagonists of a deceptively simple mathematical theorem called the pigeonhole principle. It’s easy to sum up in one short sentence: If six pigeons nestle into five pigeonholes, at least two of them must share a hole. That’s it — that’s the whole thing.

They say a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush, but for computer scientists, two birds in a hole are better still. That’s because those cohabiting birds are the protagonists of a deceptively simple mathematical theorem called the pigeonhole principle. It’s easy to sum up in one short sentence: If six pigeons nestle into five pigeonholes, at least two of them must share a hole. That’s it — that’s the whole thing. The Trump administration’s assault on higher education continues to escalate. The White House has

The Trump administration’s assault on higher education continues to escalate. The White House has