https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VQr8xDk_UaY

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VQr8xDk_UaY

Anne Boyer in The New Yorker:

Before I got sick, I’d been making plans for a place for public weeping, hoping to install in major cities a temple where anyone who needed it could get together to cry in good company and with the proper equipment. It would be a precisely imagined architecture of sadness: gargoyles made of night sweat, moldings made of longest minutes, support beams made of I-can’t-go-on-I-must-go-on. When planning the temple, I remembered the existence of people who hate those they call crybabies, and how they might respond with rage to a place full of distraught strangers—a place that exposed suffering as what is shared. It would have been something tremendous to offer those sufferers the exquisite comforts of stately marble troughs in which to collectivize their tears. But I never did this.

Before I got sick, I’d been making plans for a place for public weeping, hoping to install in major cities a temple where anyone who needed it could get together to cry in good company and with the proper equipment. It would be a precisely imagined architecture of sadness: gargoyles made of night sweat, moldings made of longest minutes, support beams made of I-can’t-go-on-I-must-go-on. When planning the temple, I remembered the existence of people who hate those they call crybabies, and how they might respond with rage to a place full of distraught strangers—a place that exposed suffering as what is shared. It would have been something tremendous to offer those sufferers the exquisite comforts of stately marble troughs in which to collectivize their tears. But I never did this.

Later, when I was sick, I was on a chemotherapy drug with a side effect of endless crying, tears dripping without agency from my eyes no matter what I was feeling or where I was. For months, my body’s sadness disregarded my mind’s attempts to convince me that I was O.K. I cried every minute, whether I was sad or not, my self a mobile, embarrassed monument of tears. I didn’t need to build the temple for weeping, then, having been one. I’ve just always hated it when anyone suffers alone. The surgeon says the greatest risk factor for breast cancer is having breasts. She won’t give me the initial results of the biopsy if I am alone. My friend Cara, who works for an hourly wage and has no time off, drives out to the suburban medical office on her lunch break so that I can get my diagnosis. In the United States, if you aren’t someone’s child or parent or spouse, the law does not guarantee you leave from work to take care of them.

As Cara and I sit in the skylighted beige of the conference room, waiting for the surgeon to arrive, Cara gives me the small knife she carries in her purse so that I can hold on to it under the table. After all these theatrical prerequisites, what the surgeon says is what we already know: I have at least one cancerous tumor, 3.8 centimetres in diameter, in my left breast. I hand the knife back to Cara damp with sweat. She then returns to work.

No one knows you have cancer until you tell them.

More here.

Santiago Zabala in Arcade:

A “call to order” is taking place in political and intellectual life in Europe and abroad. This “rappel à l’ordre” has sounded before, in France after World War I, when it was directed at avant-garde artists, demanding that they put aside their experiments and create reassuring representations for those whose worlds had been torn apart by the war. But now it is directed toward those intellectuals, politicians, and citizens who still cling to the supposedly politically correct culture of postmodernism.

A “call to order” is taking place in political and intellectual life in Europe and abroad. This “rappel à l’ordre” has sounded before, in France after World War I, when it was directed at avant-garde artists, demanding that they put aside their experiments and create reassuring representations for those whose worlds had been torn apart by the war. But now it is directed toward those intellectuals, politicians, and citizens who still cling to the supposedly politically correct culture of postmodernism.

This culture, according to the forces who claim to represent order, has corrupted facts, truth, and information, giving rise to “alternative facts,” “post-truth,” and “fake news” even though, as Stanley Fish points out, “postmodernism sets itself against the notion of facts just lying there discrete and independent, and waiting to be described. Instead it argues that fact is the achievement of argument and debate, not a pre-existing entity by whose measure argument can be assessed.” The point is that postmodernity has become a pretext for the return to order we are witnessing now in the rhetoric of right-wing populist politicians. This order reveals itself everyday as more authoritarian because it holds itself to be in possession of the essence of reality, defining truth for all human beings.

More here.

Kevin Lande in Aeon:

The brain is a computer’ – this claim is as central to our scientific understanding of the mind as it is baffling to anyone who hears it. We are either told that this claim is just a metaphor or that it is in fact a precise, well-understood hypothesis. But it’s neither. We have clear reasons to think that it’s literally true that the brain is a computer, yet we don’t have any clear understanding of what this means. That’s a common story in science. To get the obvious out of the way: your brain is not made up of silicon chips and transistors. It doesn’t have separable components that are analogous to your computer’s hard drive, random-access memory (RAM) and central processing unit (CPU). But none of these things are essential to something’s being a computer. In fact, we don’t know what is essential for the brain to be a computer. Still, it is almost certainly true that it is one.

The brain is a computer’ – this claim is as central to our scientific understanding of the mind as it is baffling to anyone who hears it. We are either told that this claim is just a metaphor or that it is in fact a precise, well-understood hypothesis. But it’s neither. We have clear reasons to think that it’s literally true that the brain is a computer, yet we don’t have any clear understanding of what this means. That’s a common story in science. To get the obvious out of the way: your brain is not made up of silicon chips and transistors. It doesn’t have separable components that are analogous to your computer’s hard drive, random-access memory (RAM) and central processing unit (CPU). But none of these things are essential to something’s being a computer. In fact, we don’t know what is essential for the brain to be a computer. Still, it is almost certainly true that it is one.

I expect that most who have heard the claim ‘the brain is a computer’ assume it is a metaphor. The mind is a computer just as the world is an oyster, love is a battlefield, and this shit is bananas (which has a metaphor inside a metaphor). Typically, metaphors are literally false. The world isn’t – as a matter of hard, humourless, scientific fact – an oyster. We don’t value metaphors because they are true; we value them, roughly, because they provide very suggestive ways of looking at things. Metaphors bring certain things to your attention (bring them ‘to light’), they encourage certain associations (‘trains of thought’), and they can help coordinate and unify people (they are ‘rallying cries’). But it is nearly impossible to ever say in a complete and literally true way what it is that someone is trying to convey with a literally false metaphor. To what, exactly, is the metaphor supposed to turn our attention? What associations is the metaphor supposed to encourage? What are we all agreeing on when we all embrace a metaphor?

More here.

The moon is out. The ice is gone. Patches of white

lounge on the wet meadow. Moonlit darkness at 6 a.m.

Again from the porch these blue mornings I hear an eagle’s cries

like God is out across the bay rubbing two mineral sheets together

slowly, with great pressure.

A single creature’s voice—or just the loudest one.

Others speak with eyes: they watch—

the frogs and beetles, sleepy bats, ones I can’t see.

Their watching is their own stamp on the world.

I cry at odd times—driving, or someone touches my shoulder

or has a nice voice on the phone.

I steel myself for the day.

.

by Nellie Bridge

from EcoTheo Review

July 2018

Robert Talisse in Liberal Currents:

The Democrats are presently courting electoral disaster. Not only is the field of those seeking the Party’s 2020 nomination heavily populated and expanding by the week, but those already in the ring, each with their own strengths and weaknesses, seem to be configured in what former President Obama recently described as a “circular firing squad,” each poised to pull the trigger on some particular opponent. The worry is that, once the smoke dissipates, every plausible nominee will have been mortally wounded in the internecine battle. A greater political gift to the Republicans could hardly be imagined.

Thus the 2020 Democratic Convention will be fraught by the same Catch-22 that plagued its predecessor. If the Party nominates one of its old guard stalwarts, it will be seen as a political machine that mindlessly manufactures “politics as usual.” This will dampen support among younger, more progressive voters. However, nominating an especially progressive candidate carries the risk of alienating older, middle-of-the-road Democrats, who happen also to belong to the demographic that is most likely to turn out on Election Day. Thus the Democrats’ dilemma: A standard-issue nominee nearly ensures a progressive third-party spoiler, driven by the contention that the DNC is hopelessly rigged in favor of milquetoast careerists over visionary change-makers. But nominating a left-progressive candidate will depress Democratic votes in electorally crucial non-coastal states.

More here.

Kyle L. Evanoff in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists:

A moonshot is on the rise on the Trump administration’s foreign policy agenda. At last month’s meeting of the National Space Council in Huntsville, Alabama, Vice President Mike Pence laid out an ambitious goal: “Return American astronauts to the moon in the next five years”—a date which would be well ahead of the 2028 target envisioned in previous NASA plans. The United States and China are locked in a new space race, he warned, and the stakes have only increased since the US-Soviet space race of the 1960s; the United States must be first to send astronauts to the moon in the twenty-first century.

A moonshot is on the rise on the Trump administration’s foreign policy agenda. At last month’s meeting of the National Space Council in Huntsville, Alabama, Vice President Mike Pence laid out an ambitious goal: “Return American astronauts to the moon in the next five years”—a date which would be well ahead of the 2028 target envisioned in previous NASA plans. The United States and China are locked in a new space race, he warned, and the stakes have only increased since the US-Soviet space race of the 1960s; the United States must be first to send astronauts to the moon in the twenty-first century.

Pence framed putting American boots on the lunar ground as a national imperative. Invoking China’s successful landing of a probe on the far side of the moon earlier this year, he suggested that Beijing has “revealed their ambition to seize the lunar strategic high ground.”

“The lunar South Pole holds great scientific, economic, and strategic value,” according to Pence, and failure to put “American astronauts, launched by American rockets, from American soil” there is “not an option.”

The vice president’s antagonistic rhetoric fails to cohere with the realities of contemporary space exploration and the dictates of sound policy making.

More here.

Maddy Crowell in The Point:

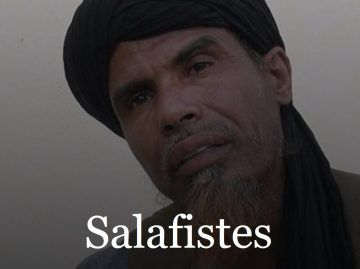

There’s a scene early on in the French documentary Salafistes (“Jihadists”) where the camera spans over a throng of people gathered in a village in northern Mali: the crowd is there to watch as the “Islamic Police” cut off a 25-year-old man’s hand. The shot zooms in as the young man, tethered in ropes around a chair, slumps over, unconscious, while his hand is sawed off with a small, serrated blade. Young boys in the background howl incoherently. In the next scene, the same young man is filmed lying in a bed cocooned by a lime green mosquito net, his severed limb wrapped in thick white bandages. “This is the application of sharia,” he tells the camera. “I committed a theft; in accordance with sharia my hand was amputated. Once I recover I will be purified and all my sins erased.” The trace of a drugged smile lingers across his face.

There’s a scene early on in the French documentary Salafistes (“Jihadists”) where the camera spans over a throng of people gathered in a village in northern Mali: the crowd is there to watch as the “Islamic Police” cut off a 25-year-old man’s hand. The shot zooms in as the young man, tethered in ropes around a chair, slumps over, unconscious, while his hand is sawed off with a small, serrated blade. Young boys in the background howl incoherently. In the next scene, the same young man is filmed lying in a bed cocooned by a lime green mosquito net, his severed limb wrapped in thick white bandages. “This is the application of sharia,” he tells the camera. “I committed a theft; in accordance with sharia my hand was amputated. Once I recover I will be purified and all my sins erased.” The trace of a drugged smile lingers across his face.

If the uncensored brutality of the mutilation seems gratuitous, it is hardly an anomaly in Salafistes. This is part of the point of a documentary that gained rare and dangerous access to the usually closed-off backyard of jihadi territory. After the amputation, the Islamic Police—members of Al Qaeda-linked terrorist groups—surround the young man in a halo of bored silence, as their leader, Sanda Ould Boumama, clutches his shoulder.

More here.

Today, in a crowded doctor’s waiting room,

sat a sad little man of maybe fifty,

wearing a baggy black suit, a black shirt

buttoned to the neck, and black work shoes,

his thinning silver hair oiled back,

and he began singing, but softly, the words

to a song that played from hidden speakers

somewhere above our heavy silence,

music we hadn’t noticed before he began,

in his whispery voice, to sing for us.

by Ted Kooser

from Kindest Regards

Copper Canyon Press, 2018

Kathryn Hughes at The Guardian:

In 1142 Empress Matilda escaped from Oxford Castle where she was being held by her dynastic rival, Stephen of Blois. Since it was a snowy December, the self-proclaimed “Lady of the English” wrapped herself in a white fur cloak to blend into the snowy landscape before skating down the frozen river Thames to freedom. As a bedtime story for history-mad girls, Matilda’s flight has always had everything: a heroine outtricking a boy and a nod to the enchantment of Narnia.

In 1142 Empress Matilda escaped from Oxford Castle where she was being held by her dynastic rival, Stephen of Blois. Since it was a snowy December, the self-proclaimed “Lady of the English” wrapped herself in a white fur cloak to blend into the snowy landscape before skating down the frozen river Thames to freedom. As a bedtime story for history-mad girls, Matilda’s flight has always had everything: a heroine outtricking a boy and a nod to the enchantment of Narnia.

Catherine Hanley, though, is writing for grown-ups, and her intention in this impressive study is to remove Matilda’s cloak of invisibility – there have been remarkably few books written about the woman who was arguably England’s first regnant queen – and restore her to full subjecthood. For while Matilda never actually led her troops into battle like Jeanne d’Arc, she was present in the generals’ tent, directing the next stage in her campaign to conquer the country.

more here.

Stephen Phillips at The LA Times:

The explosion on April 26, 1986, at the V.I. Lenin, or Chernobyl, Atomic Energy Station in what was then the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic is thought to have “vaporized” one worker on the spot. Another 30, drenched in fatal doses of radiation, died gruesome, lingering deaths. As of 2005, as many as 5,000 additional cancer deaths were projected locally — among 25,000 extra cancer cases Europe-wide. Contamination rendered 1,838-plus square miles “uninhabitable.” And a spectral column of radioactive gases escaped into the atmosphere, setting people on edge from Stockholm to San Francisco. It was the worst nuclear accident in history and could have been far worse.

The explosion on April 26, 1986, at the V.I. Lenin, or Chernobyl, Atomic Energy Station in what was then the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic is thought to have “vaporized” one worker on the spot. Another 30, drenched in fatal doses of radiation, died gruesome, lingering deaths. As of 2005, as many as 5,000 additional cancer deaths were projected locally — among 25,000 extra cancer cases Europe-wide. Contamination rendered 1,838-plus square miles “uninhabitable.” And a spectral column of radioactive gases escaped into the atmosphere, setting people on edge from Stockholm to San Francisco. It was the worst nuclear accident in history and could have been far worse.

It also helped precipitate the demise of the Soviet Union. And this — the dissolution of the geopolitical entity in which it occurred — has contributed to its effacement: buried under the accretions of history like the radioactive debris smothered by “absorbents” during its cleanup. Thirty-three years later, what happened exactly at Chernobyl?

more here.

Julian Wolfreys and Paweł Huelle at The Quarterly Conversation:

Gdańsk was a city of the borders for many years, with a prevailing influence of German culture, German music, German language, because even the Polish proletariat when they came from the villages were Germanized, because with the German language they had better chances. But there used to be about 15%-20% Polish speaking people, 3% French people, 2% English people, 3.5% Russians, Scottish people as well, a lot of Dutch people; this was a typical city of the borders. This was over after the Polish partition of 1795. And then Gdańsk, which used to be a rich merchant city, a merchant emporium, became a provincial Prussian city. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, these were periods of the great German nationalisms, which end up with the crime of 1939, because most of the Polish people here were murdered at that time. Surprisingly, the Jews could leave. Because this used to be the Free City of Gdańsk, the so-called ‘Free City’, and the authorities of Gdańsk signed an agreement with the Jewish Community in 1939, more or less, perhaps one year earlier, and while the war was still going on, until 1940 the Jewish population was still leaving. So, the multicultural city was over with the Prussian partition. Then, after the war, 99% of the German population left, and Polish people from various parts of former Poland came, from burned-down Warsaw, from Wilno, or from the Eastern borders, from those parts; so, people only came back to the idea of multiculturalism, after 1989, with the end of Communism. But, if ever we speak of multiculturalism in Gdańsk, we speak of the distant past. Of course, it’s a very good example of something to reach for, but it’s a deep past.

Gdańsk was a city of the borders for many years, with a prevailing influence of German culture, German music, German language, because even the Polish proletariat when they came from the villages were Germanized, because with the German language they had better chances. But there used to be about 15%-20% Polish speaking people, 3% French people, 2% English people, 3.5% Russians, Scottish people as well, a lot of Dutch people; this was a typical city of the borders. This was over after the Polish partition of 1795. And then Gdańsk, which used to be a rich merchant city, a merchant emporium, became a provincial Prussian city. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, these were periods of the great German nationalisms, which end up with the crime of 1939, because most of the Polish people here were murdered at that time. Surprisingly, the Jews could leave. Because this used to be the Free City of Gdańsk, the so-called ‘Free City’, and the authorities of Gdańsk signed an agreement with the Jewish Community in 1939, more or less, perhaps one year earlier, and while the war was still going on, until 1940 the Jewish population was still leaving. So, the multicultural city was over with the Prussian partition. Then, after the war, 99% of the German population left, and Polish people from various parts of former Poland came, from burned-down Warsaw, from Wilno, or from the Eastern borders, from those parts; so, people only came back to the idea of multiculturalism, after 1989, with the end of Communism. But, if ever we speak of multiculturalism in Gdańsk, we speak of the distant past. Of course, it’s a very good example of something to reach for, but it’s a deep past.

more here.

John Mullan in The Guardian:

As we await the final season of Game of Thrones, curiosity settles on a single question: how will it end? Fan sites buzz with speculation about what the most convincing conclusion could be. Surely Jon Snow’s true lineage will be revealed to him? Won’t we have to find out the truth about Cersei’s pregnancy? Will the White Walkers finally be defeated? And above all, who will reign at the end? The makers of the series have set themselves a challenge: conjuring what the great literary critic Frank Kermode called “the sense of an ending”, and they can no longer rely on the original novels of George RR Martin.

As we await the final season of Game of Thrones, curiosity settles on a single question: how will it end? Fan sites buzz with speculation about what the most convincing conclusion could be. Surely Jon Snow’s true lineage will be revealed to him? Won’t we have to find out the truth about Cersei’s pregnancy? Will the White Walkers finally be defeated? And above all, who will reign at the end? The makers of the series have set themselves a challenge: conjuring what the great literary critic Frank Kermode called “the sense of an ending”, and they can no longer rely on the original novels of George RR Martin.

…The most extraordinary example is one of the best of all 19th-century novels, Great Expectations. For this story, which had been appearing in weekly instalments in his own magazine, All the Year Round, Dickens wrote one of the few unhappy endings of his career. In the first draft, Pip returns from years working abroad. He is walking down Piccadilly with the young son of Joe and Biddy, named Pip after him. A lady in a carriage summons him; it is Estella. She is now married to a doctor who lives in Shropshire: “I am greatly changed, I know; but I thought you would like to shake hands with Estella, too, Pip. Lift up that pretty child and let me kiss it!” (She supposed the child, I think, to be my child.) I was very glad afterwards to have had the interview; for, in her face and in her voice, and in her touch, she gave me the assurance, that suffering had been stronger than Miss Havisham’s teaching, and had given her a heart to understand what my heart used to be.

Piercingly, Dickens and his narrator allow Estella to depart on a misunderstanding: she believes that Pip has married and had a son – but in fact he is alone, his capacity for love cauterised by his experiences. He does not get Estella; he does not get anyone. When Dickens’s friend and fellow novelist Edward Bulwer-Lytton read this he was horrified. What would the author’s loyal readers, who expected their usual happy ending, think? Dickens was persuaded to write a new ending, in which Estella is husbandless when she meets Pip again in the ruins of Satis House. This time the narrator sees “no shadow of a future parting” from the woman he loves. Dickens, who scanned his monthly or weekly sales with just the attention a TV producer might give to viewing figures, succumbed to fears about what his audience wanted. He scrapped a brilliant ending in favour of a merely serviceable one. Have the scriptwriters of Game of Thrones been worrying in a similar fashion about what their devotees want and expect? Or will they give us an ending as arbitrarily brutal as the world they have created?

More here.

Timothy Egan in The New York Times:

These days, no less an authority than Sarah Huckabee Sanders, the White House press secretary, said recently that God “wanted Donald Trump to become president.”

These days, no less an authority than Sarah Huckabee Sanders, the White House press secretary, said recently that God “wanted Donald Trump to become president.”

She offered no sourcing for this assertion, as is the case for vaporous claims that rise from the rot of the Trump presidency on a daily basis. But in blaming God for Trump, Sanders echoed a widespread Republican belief that the most outwardly amoral man ever to occupy the White House is an instrument of divine power. He’s part of the master plan. Mocking Sanders and the many Ned Flanders of the G.O.P. team is unlikely to make much of a dent. Nearly half of all Republicans believe God wanted Trump to win the election. To them, secular snark is a merit badge on the MAGA hat. But there is a better way to sway the electorate of faith, as the rising Democratic stars Pete Buttigieg and Stacey Abrams have shown us. They apply something like a “What Would Jesus Do?” test to rouse religious conscience on the political battlefield.

Buttigieg, the 37-year-old mayor of South Bend, Ind., is a Navy veteran who served in Afghanistan, a Rhodes scholar, married to a junior high school teacher. He’s gay and, more surprising for a modern Democrat, he is an out Christian, as quick to quote St. Augustine as Abraham Lincoln. On Sunday, he is expected to formally announce his run for president. Like Abrams and Senator Cory Booker, Mayor Pete says his faith made him a progressive. Scripture directs him to defend the poor, the sick, the marginalized, the societal castoffs.

But Buttigieg goes much further than mere Bible-citing. He’s taking it directly to Trump and to Vice President Mike Pence, who flashes his piety like a seven-carat diamond on his pinkie finger. It’s hard to look at the actions of President Trump, Buttigieg said, “and believe they are the actions of somebody who believes in God.”

More here.

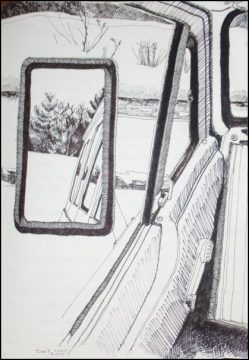

Once I wrote, “On the mule of time

we sit backwards. It carries us forward

anyway, though things appear a little askew.”

Now I walk into a room with a hundred

rearview mirrors from lost and forgotten

vehicles and think, “At my age, I’m on no mule,

but in a fast car, on a freeway, exceeding

the speed limit,” and think again, “Even the sun

is eight minutes ago,” and think again,

“Consciousness is a rearview mirror.

Whatever you see has been already.”

by Nils Peterson

from All the Marvelous Stuff

Caesura Editions, 2019

Drawing, Rearview, Jim Culleny

Mary F. Corey at the LARB:

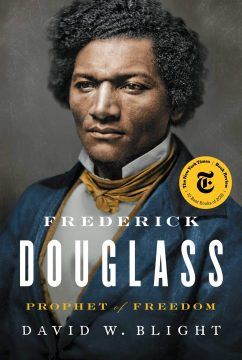

In Prophet of Freedom, Blight allows us to experience both the exuberance and the difficulties of a life acted out on stages. We see Douglass, as a small boy, gathering damp pages from a discarded Bible out of the gutter so he could learn how to read. We are shown the young, proud orator being shunted into filthy, segregated train cars even as he traveled to address throngs of adoring fans. And we are at the Rochester train station to see his wife Anna rush to meet him with a bundle of freshly ironed shirts before returning to her job making shoes, or caring for their five children, while the abolitionist rock star continued on his way. We are with him near the end of his life when he climbed a rocky crag near the Acropolis and lingered there to read St. Paul’s famous “Address to the Athenians,” in which the Apostle declared all people to be the “offspring” of God and that God “hath made of one blood all nations of men for to dwell on all the face of the earth.”

In Prophet of Freedom, Blight allows us to experience both the exuberance and the difficulties of a life acted out on stages. We see Douglass, as a small boy, gathering damp pages from a discarded Bible out of the gutter so he could learn how to read. We are shown the young, proud orator being shunted into filthy, segregated train cars even as he traveled to address throngs of adoring fans. And we are at the Rochester train station to see his wife Anna rush to meet him with a bundle of freshly ironed shirts before returning to her job making shoes, or caring for their five children, while the abolitionist rock star continued on his way. We are with him near the end of his life when he climbed a rocky crag near the Acropolis and lingered there to read St. Paul’s famous “Address to the Athenians,” in which the Apostle declared all people to be the “offspring” of God and that God “hath made of one blood all nations of men for to dwell on all the face of the earth.”

more here.

Olivia Laing at The Paris Review:

Here’s the setup: palette, chair, mirror. The mirror is bandaged together with red-and-white tape that says FRAGILE, but let’s not make too much of that. The original plan was written on a scrap of paper: “small heads—meditations—buy lots of small boards.” The first was painted on January 1, 2018, “the worst day of the year,” not that the rest of the year was that much brighter. Joffe’s marriage was breaking up. She painted herself nearly every day, sometimes at night, always in fairly pitiless light.

Speaking broadly for a minute, she looks in this extraordinary series of self-portraits like someone almost warping under a heavy weight. Bowed down, weighted by feeling, she peers back at herself, artist prowling after sitter, avid to catch pouches, moles, sags, bags, and quirks of flesh.

more here.