Dan Chiasson at The New Yorker:

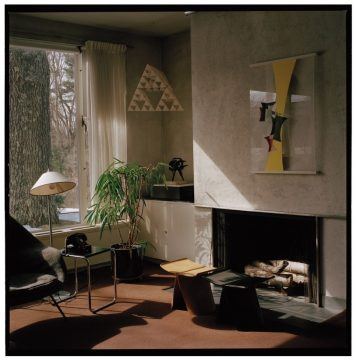

Because his genius was untethered to his misery, and because he often handed his ideas off to others, Gropius is a tricky subject for a biographer. Following his lead, we focus on his colorful and eccentric supporting players. As MacCarthy suggests, he had none of the puffery we associate with great architects. He was more a technocrat than a shaman. In a sense, therefore, MacCarthy’s book is a biography of the Bauhaus itself. It’s a story that she presents with a distinctly human-seeming arc. Its childhood unfolded in Weimar, where Itten impressed the students with his mantra, “Play becomes party—party becomes work—work becomes play,” and Gropius read the Christmas story aloud every year. But by early adolescence, in the mid-twenties, the Bauhaus had outstayed its welcome. In 1924, a new provincial government threatened to cut off the school’s subsidies. Nazi factions in the region supposed that all those foreign-looking students were Jews or Jewish sympathizers. The following year, Gropius moved the school to Dessau, an engineering and manufacturing center, southwest of Berlin. There, for the first time, the Bauhaus built itself a campus.

Because his genius was untethered to his misery, and because he often handed his ideas off to others, Gropius is a tricky subject for a biographer. Following his lead, we focus on his colorful and eccentric supporting players. As MacCarthy suggests, he had none of the puffery we associate with great architects. He was more a technocrat than a shaman. In a sense, therefore, MacCarthy’s book is a biography of the Bauhaus itself. It’s a story that she presents with a distinctly human-seeming arc. Its childhood unfolded in Weimar, where Itten impressed the students with his mantra, “Play becomes party—party becomes work—work becomes play,” and Gropius read the Christmas story aloud every year. But by early adolescence, in the mid-twenties, the Bauhaus had outstayed its welcome. In 1924, a new provincial government threatened to cut off the school’s subsidies. Nazi factions in the region supposed that all those foreign-looking students were Jews or Jewish sympathizers. The following year, Gropius moved the school to Dessau, an engineering and manufacturing center, southwest of Berlin. There, for the first time, the Bauhaus built itself a campus.

more here.

Literature is fire,” Mario Vargas Llosa declared in 1967, when he accepted a prize commemorating Rómulo Gallegos, the esteemed Venezuelan novelist and former president. Gallegos represented the center-left tradition in Latin America, and Vargas Llosa was determined to challenge his audience from the left. Literature, the Peruvian novelist continued, “means nonconformism and rebellion…. Within ten, twenty or fifty years, the hour of social justice will arrive in our countries, as it has in Cuba, and the whole of Latin America will have freed itself from the order that despoils it, from the castes that exploit it, from the forces that now insult and repress it.” Nearly 40 years later, in 2005, Vargas Llosa received a very different sort of prize and delivered a very different kind of speech. Accepting the Irving Kristol Award from the American Enterprise Institute, he denounced the Cuban government and called Fidel Castro an “authoritarian fossil,” praised the Austrian School economist Ludwig von Mises as a “great liberal thinker,” and defended calls for privatizing pensions. It was quite a remarkable transformation. In the opening paragraph of Vargas Llosa’s 1969 novel, Conversation in the Cathedral, the protagonist asks: “At what precise moment had Peru fucked itself up?” It is a question that many people have asked as well of Peru’s greatest novelist.

Literature is fire,” Mario Vargas Llosa declared in 1967, when he accepted a prize commemorating Rómulo Gallegos, the esteemed Venezuelan novelist and former president. Gallegos represented the center-left tradition in Latin America, and Vargas Llosa was determined to challenge his audience from the left. Literature, the Peruvian novelist continued, “means nonconformism and rebellion…. Within ten, twenty or fifty years, the hour of social justice will arrive in our countries, as it has in Cuba, and the whole of Latin America will have freed itself from the order that despoils it, from the castes that exploit it, from the forces that now insult and repress it.” Nearly 40 years later, in 2005, Vargas Llosa received a very different sort of prize and delivered a very different kind of speech. Accepting the Irving Kristol Award from the American Enterprise Institute, he denounced the Cuban government and called Fidel Castro an “authoritarian fossil,” praised the Austrian School economist Ludwig von Mises as a “great liberal thinker,” and defended calls for privatizing pensions. It was quite a remarkable transformation. In the opening paragraph of Vargas Llosa’s 1969 novel, Conversation in the Cathedral, the protagonist asks: “At what precise moment had Peru fucked itself up?” It is a question that many people have asked as well of Peru’s greatest novelist. IT WAS A

IT WAS A  The great surprise of this debate turned out to be how much in common the old-school Marxist and the Canadian identity politics refusenik had.

The great surprise of this debate turned out to be how much in common the old-school Marxist and the Canadian identity politics refusenik had. You might find your car dying on the freeway while other vehicles around you lose control and crash. You might see the lights going out in your city, or glimpse an airplane falling out of the sky. You’ve been in a blackout before but this one is different.

You might find your car dying on the freeway while other vehicles around you lose control and crash. You might see the lights going out in your city, or glimpse an airplane falling out of the sky. You’ve been in a blackout before but this one is different. “Has economics failed us?” Larry Summers, the former president of Harvard and economic adviser for presidents Barack Obama and Bill Clinton, recently asked

“Has economics failed us?” Larry Summers, the former president of Harvard and economic adviser for presidents Barack Obama and Bill Clinton, recently asked  What’s been preoccupying me the last two or three years is what it would be like to live with a fully embodied artificial consciousness, which means leaping over every difficulty that we’ve heard described this morning by Rod Brooks. The building of such a thing is probably scientifically useless, much like putting a man on the moon when you could put a machine there, but it has an ancient history.

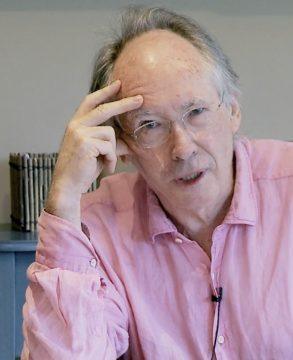

What’s been preoccupying me the last two or three years is what it would be like to live with a fully embodied artificial consciousness, which means leaping over every difficulty that we’ve heard described this morning by Rod Brooks. The building of such a thing is probably scientifically useless, much like putting a man on the moon when you could put a machine there, but it has an ancient history. WHEN JAL MEHTA

WHEN JAL MEHTA One afternoon in August 2010, in a conference hall perched on the edge of San Francisco Bay, a 34-year-old Londoner called Demis Hassabis took to the stage. Walking to the podium with the deliberate gait of a man trying to control his nerves, he pursed his lips into a brief smile and began to speak: “So today I’m going to be talking about different approaches to building…” He stalled, as though just realising that he was stating his momentous ambition out loud. And then he said it: “AGI”. AGI stands for artificial general intelligence, a hypothetical computer program that can perform intellectual tasks as well as, or better than, a human.

One afternoon in August 2010, in a conference hall perched on the edge of San Francisco Bay, a 34-year-old Londoner called Demis Hassabis took to the stage. Walking to the podium with the deliberate gait of a man trying to control his nerves, he pursed his lips into a brief smile and began to speak: “So today I’m going to be talking about different approaches to building…” He stalled, as though just realising that he was stating his momentous ambition out loud. And then he said it: “AGI”. AGI stands for artificial general intelligence, a hypothetical computer program that can perform intellectual tasks as well as, or better than, a human.  Geoffrey Wildanger in the Boston Review:

Geoffrey Wildanger in the Boston Review: James Meadway in Novara Media:

James Meadway in Novara Media: Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman in The National Interest:

Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman in The National Interest: Francisco Goldman in the NYT:

Francisco Goldman in the NYT: Nathan Robinson in Current Affairs:

Nathan Robinson in Current Affairs: T

T