Coco Fusco at the NYRB:

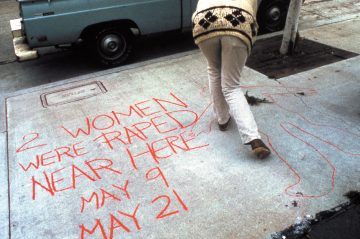

Vivien Green Fryd’s new book, Against Our Will: Sexual Trauma in American Art Since 1970, arrives at this historical moment to offer an overview of American feminist artists’ treatment of rape. Fryd takes the first part of her title from Susan Brownmiller’s best-selling Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape (1975), which called for a redefinition of rape as a political crime against women. Although some readers criticized the book for its comparisons of rape with lynching, Brownmiller’s argument that rape was an instrument of oppression against all women and that Freudian psychoanalysis had unjustly discredited women’s accounts of rape (by presuming them to be fantasies) helped to change laws relating to sex crimes. Rape shield laws were adopted in the late 1970s to prohibit the admission of evidence of or the questioning of rape complainants about their past sexual behavior.

Similarly, Fryd concentrates on feminist art that foregrounds the pervasiveness of rape, proposing that such art should be valued for its capacity to empower survivors and enhance public awareness. She focuses on how the experience of the survivor rather than the action of the perpetrator is represented in art and how it affects viewers.

more here.

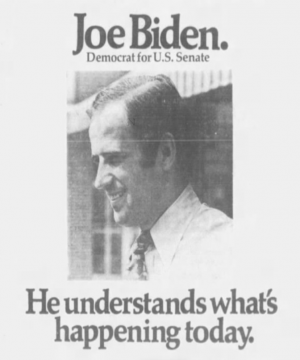

“Joe Biden. He understands what’s happening today.”

“Joe Biden. He understands what’s happening today.” Shakespeare’s power to endure has been ensured by twin track modes of survival: his life on the page and on the stage. His texts are pored over scrupulously by academics, read dreamily by kids and scanned with soft remembrance by the sere. At any given moment, his dramatic verse is sung, shouted, muttered and sometimes spoken with the warm assurance it needs, from hundreds of stages to thousands of eager spectators.

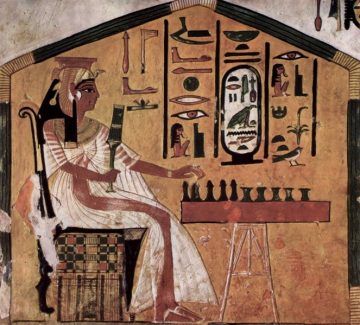

Shakespeare’s power to endure has been ensured by twin track modes of survival: his life on the page and on the stage. His texts are pored over scrupulously by academics, read dreamily by kids and scanned with soft remembrance by the sere. At any given moment, his dramatic verse is sung, shouted, muttered and sometimes spoken with the warm assurance it needs, from hundreds of stages to thousands of eager spectators. Ten thousand years ago, in the Neolithic period, before human beings began making pottery, we were playing games on flat stone boards drilled with two or more rows of holes.

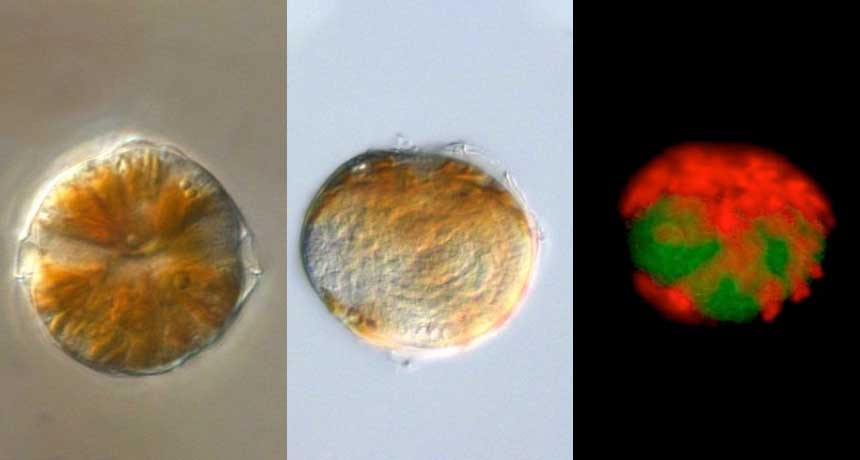

Ten thousand years ago, in the Neolithic period, before human beings began making pottery, we were playing games on flat stone boards drilled with two or more rows of holes. One parasite that feeds on algae is so voracious that it even stole its own mitochondria’s DNA.

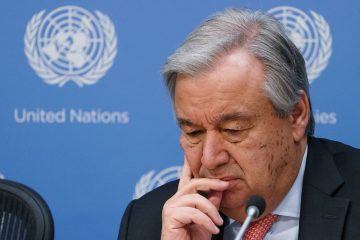

One parasite that feeds on algae is so voracious that it even stole its own mitochondria’s DNA. Halfway through his first five-year term, U.N. Secretary General

Halfway through his first five-year term, U.N. Secretary General  P

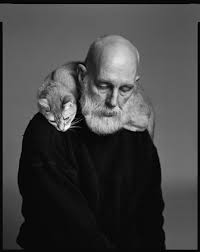

P “I’ll be wearing a blue anorak,” he said to me on the phone, so I could identify him when we met. We were more like immediate siblings than date possibilities for each other, and I repeated this line about a blue anorak to him for twenty years. He claims there was no blue anorak and what the fuck is an anorak, anyhow? But that’s what I remember. We went to see a Gerhard Richter show at Marian Goodman. I was aware that Alex’s grandfather Alexander Lippisch was a famous Luftwaffe aeronautical engineer who was recruited to White Sands Missile Range after the war. Looking at Richter’s paintings together, I immediately associated Richter’s blend of formal precision and German trauma with Alex’s. From the gallery, we walked into Central Park. We sat on a rock and Alex told me that one day, on a very similar rock, he’d been on acid with his friend the painter Alexander Ross. As they sat on this rock, tripping, they watched Alex Katz approach a Sabrett cart and buy a hot dog. Three painters named Alex: two on acid, one eating a hot dog. They left and went to Alex Brown’s place on Forsyth Street and, still tripping, walked into the scene of a dramatic drug bust.

“I’ll be wearing a blue anorak,” he said to me on the phone, so I could identify him when we met. We were more like immediate siblings than date possibilities for each other, and I repeated this line about a blue anorak to him for twenty years. He claims there was no blue anorak and what the fuck is an anorak, anyhow? But that’s what I remember. We went to see a Gerhard Richter show at Marian Goodman. I was aware that Alex’s grandfather Alexander Lippisch was a famous Luftwaffe aeronautical engineer who was recruited to White Sands Missile Range after the war. Looking at Richter’s paintings together, I immediately associated Richter’s blend of formal precision and German trauma with Alex’s. From the gallery, we walked into Central Park. We sat on a rock and Alex told me that one day, on a very similar rock, he’d been on acid with his friend the painter Alexander Ross. As they sat on this rock, tripping, they watched Alex Katz approach a Sabrett cart and buy a hot dog. Three painters named Alex: two on acid, one eating a hot dog. They left and went to Alex Brown’s place on Forsyth Street and, still tripping, walked into the scene of a dramatic drug bust.

A young bank teller is shot dead during a robbery. The robber flees in a stolen van and is chased down the motorway by a convoy of police cars. Careening through traffic, the robber runs several cars off the road and clips several more. Eventually, the robber pulls off the motorway and attempts to escape into the hills on foot, the police in hot pursuit. After several tense minutes, the robber pulls a gun on the cops and is promptly killed in a hail of gunfire. It is later revealed the robber is a career criminal with a history of violent crime stretching all the way back to high school.

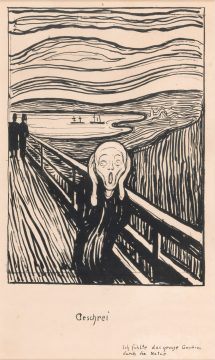

A young bank teller is shot dead during a robbery. The robber flees in a stolen van and is chased down the motorway by a convoy of police cars. Careening through traffic, the robber runs several cars off the road and clips several more. Eventually, the robber pulls off the motorway and attempts to escape into the hills on foot, the police in hot pursuit. After several tense minutes, the robber pulls a gun on the cops and is promptly killed in a hail of gunfire. It is later revealed the robber is a career criminal with a history of violent crime stretching all the way back to high school. At the start of the 20th century Sigmund Freud observed the psychological phenomenon of “repetition compulsion”, the pathological desire to repeat a pattern of behaviour over and over again. He no doubt would have diagnosed the painter Edvard Munch with such an affliction. As the British Museum’s new exhibition of his work demonstrates, Munch returned obsessively to certain visual motifs: uncanny sunsets, zombie-like faces, threateningly sexualised female bodies.

At the start of the 20th century Sigmund Freud observed the psychological phenomenon of “repetition compulsion”, the pathological desire to repeat a pattern of behaviour over and over again. He no doubt would have diagnosed the painter Edvard Munch with such an affliction. As the British Museum’s new exhibition of his work demonstrates, Munch returned obsessively to certain visual motifs: uncanny sunsets, zombie-like faces, threateningly sexualised female bodies. Ammon Shea loves dictionaries – especially the OED. He loves the OED so much, he read it – the whole thing, in its second edition: 21,730 pages with around 59 million words. It took him a year, full-time, and he wrote a book about it, titled

Ammon Shea loves dictionaries – especially the OED. He loves the OED so much, he read it – the whole thing, in its second edition: 21,730 pages with around 59 million words. It took him a year, full-time, and he wrote a book about it, titled  These days you can dismiss anything you don’t like by calling it “a religion.” Science, for instance,

These days you can dismiss anything you don’t like by calling it “a religion.” Science, for instance,  How should we make sense of the Easter Sunday church and hotel

How should we make sense of the Easter Sunday church and hotel