Eviction

the whites cry in their houses

because they’ve had to evict the guests.

the last names and the properties cry

because they’ve burned

the worms’ deeds.

how sad the disillusionment!

how sad the death of love and hope!

the writings cry for the forgotten oralities.

the coldness of the rebel incites the handkerchiefs to come out

and cry through the streets like mary magdalene.

the world ends and those who end it never end up crying,

but when they reach the water ay ay what laments

what bodies of water that flood the planet.

the buried mountains of my island

sit like lost treasures at the bottom of a sea

that is more spume than water.

this poem is personal.

as personal as colonialism and private property.

this poem doesn’t cry because it is worse than an evicted tenant.

this poem doesn’t have friends or time to move,

but still moves.

(a curse on the house that still smells like my mouth)

either way, what is a poem without the rent,

a couple without equality or love

between landlord and tenant?

wouldn’t pain be inevitable

if you don’t pay the first of the month?

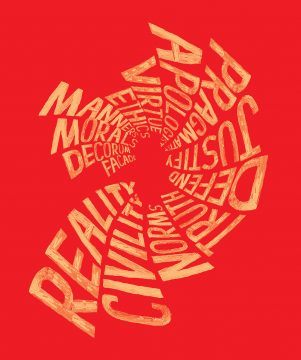

they say that what i am saying is unfair

that really we should be careful.

we all have bills.

the world makes us cruel.

but i am not of the world,

not even of this planet.

i happened to land here

and my ship ran out of gas.

i stayed because i had no choice.

i fell in love because soy una pendeja

and because the people here are beautiful

when they don’t kick us out.

since my arrival,

i’ve had various lovely houses.

one had green walls

and a white and open kitchen.

another smelled like sage and rusty books.

my favorite had two cats and two people in love.

all evicted me to drain the roofs.

the houses with their whites cry

over the end of the neighborhoods

and with their white nostalgia

for the end of childhood and backyards.

by Raquel Salas Rivera

from Split This Rock

Read more »

Vladimir Nabokov, whose 120th anniversary we mark this Spring, remains one of the 20th Century’s most acclaimed and enduring writers. He keeps turning up on

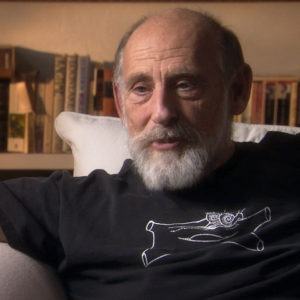

Vladimir Nabokov, whose 120th anniversary we mark this Spring, remains one of the 20th Century’s most acclaimed and enduring writers. He keeps turning up on  For decades now physicists have been struggling to reconcile two great ideas from a century ago: general relativity and quantum mechanics. We don’t yet know the final answer, but the journey has taken us to some amazing places. A leader in this quest has been Leonard Susskind, who has helped illuminate some of the most mind-blowing ideas in quantum gravity: the holographic principle, the string theory landscape, black-hole complementarity, and others. He has also become celebrated as a writer, speaker, and expositor of mind-blowing ideas. We talk about black holes, quantum mechanics, and the most exciting new directions in quantum gravity.

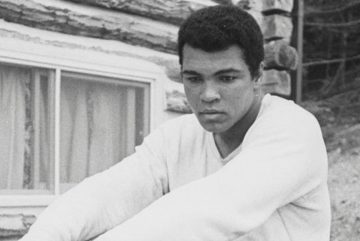

For decades now physicists have been struggling to reconcile two great ideas from a century ago: general relativity and quantum mechanics. We don’t yet know the final answer, but the journey has taken us to some amazing places. A leader in this quest has been Leonard Susskind, who has helped illuminate some of the most mind-blowing ideas in quantum gravity: the holographic principle, the string theory landscape, black-hole complementarity, and others. He has also become celebrated as a writer, speaker, and expositor of mind-blowing ideas. We talk about black holes, quantum mechanics, and the most exciting new directions in quantum gravity. The opening frame of “What’s My Name” shows Ali explaining that should his story ever be told, he wants it done in full. So, there are no talking heads or narration, because who better to tell such a remarkable, revolutionary story than Muhammad Ali himself? His interviews and words guide us through his life, from early childhood until his final days, as he endures the bodily constraints of Parkinson’s disease. Ali’s famous, rhythmic one-liners, like “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee,” are accompanied by his critical analysis about race, white supremacy and his politics, which are global.

The opening frame of “What’s My Name” shows Ali explaining that should his story ever be told, he wants it done in full. So, there are no talking heads or narration, because who better to tell such a remarkable, revolutionary story than Muhammad Ali himself? His interviews and words guide us through his life, from early childhood until his final days, as he endures the bodily constraints of Parkinson’s disease. Ali’s famous, rhythmic one-liners, like “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee,” are accompanied by his critical analysis about race, white supremacy and his politics, which are global.

Trilling rather disliked the label “literary critic” and was pleased when Étienne Gilson suggested, in 1955, that he was not one. (Just what Gilson proposed him to be is not made clear.) All the same, twenty years after the Gilson exchange, Trilling would write to someone, who had sent him some offprints, to aver that he should “best refer to me as a critic of literature.” He did not much care for the New Criticism of Allen Tate, William Empson, and Cleanth Brooks, calling it snide and restrictive. Leon Edel, more a literary historian than a critic to be sure, he thought dull-witted (“a very stupid man”). One would not expect the life of a literary critic to be full of high adventure and derring-do, and the composite portrait of a critic’s life as painted in Trilling’s letters appears a largely unruffled if not a completely serene one. He married young and stay married to the same woman for his entire life. If there were any occasions of extramarital desire, much less action, they are not even intimated here. There is only a single rather explicit letter, to his wife, Diana, in which he talks about sex, and he never once swears and rarely uses slang. (When he writes in a letter to Norman Mailer that sex should be a subject for novelists for “ten, maybe twelve years; then everybody shut up,” it is a bit of a shock.)

Trilling rather disliked the label “literary critic” and was pleased when Étienne Gilson suggested, in 1955, that he was not one. (Just what Gilson proposed him to be is not made clear.) All the same, twenty years after the Gilson exchange, Trilling would write to someone, who had sent him some offprints, to aver that he should “best refer to me as a critic of literature.” He did not much care for the New Criticism of Allen Tate, William Empson, and Cleanth Brooks, calling it snide and restrictive. Leon Edel, more a literary historian than a critic to be sure, he thought dull-witted (“a very stupid man”). One would not expect the life of a literary critic to be full of high adventure and derring-do, and the composite portrait of a critic’s life as painted in Trilling’s letters appears a largely unruffled if not a completely serene one. He married young and stay married to the same woman for his entire life. If there were any occasions of extramarital desire, much less action, they are not even intimated here. There is only a single rather explicit letter, to his wife, Diana, in which he talks about sex, and he never once swears and rarely uses slang. (When he writes in a letter to Norman Mailer that sex should be a subject for novelists for “ten, maybe twelve years; then everybody shut up,” it is a bit of a shock.) There is a way in which all of Bette Howland’s characters seem like visitors from a parallel universe, where they are free rather than confined. This is the eponymous visitor in the opening story of this collection: “I was catching on at last. The bad roads, the crash, the minor injury. This petty bureaucrat. This place. Sir? I’m dead? Is that it? I’m dead? … That’s what they all want to know! he said. But that’s the whole show! I can’t give that away, can I?” An uncle’s young wife is “a big handsome Southern girl, rawboned, rock jawed, her pale head dropped over her knitting. Peculiarly pale; translucent, like rock candy, and almost as brittle.” It is as if they step into a room accompanied by their own lighting. “ ‘When are you going to get married?’ Uncle Rudy asked, towering over me.” Imagination is what she calls what she does with them, imaginative selection from the panoply of life. “He’s a scofflaw. He’ll go out of his way to park illegally. He’ll drive around the block looking for a No Parking sign or a nice little fire hydrant.” Reading the prose brings a Bette I’d forgotten—a glass of Scotch, how she threw back her head and uproariously laughed. Ah, yes; here’s the one with verve, the woman in the fedora photo.

There is a way in which all of Bette Howland’s characters seem like visitors from a parallel universe, where they are free rather than confined. This is the eponymous visitor in the opening story of this collection: “I was catching on at last. The bad roads, the crash, the minor injury. This petty bureaucrat. This place. Sir? I’m dead? Is that it? I’m dead? … That’s what they all want to know! he said. But that’s the whole show! I can’t give that away, can I?” An uncle’s young wife is “a big handsome Southern girl, rawboned, rock jawed, her pale head dropped over her knitting. Peculiarly pale; translucent, like rock candy, and almost as brittle.” It is as if they step into a room accompanied by their own lighting. “ ‘When are you going to get married?’ Uncle Rudy asked, towering over me.” Imagination is what she calls what she does with them, imaginative selection from the panoply of life. “He’s a scofflaw. He’ll go out of his way to park illegally. He’ll drive around the block looking for a No Parking sign or a nice little fire hydrant.” Reading the prose brings a Bette I’d forgotten—a glass of Scotch, how she threw back her head and uproariously laughed. Ah, yes; here’s the one with verve, the woman in the fedora photo. WASHINGTON — Humans are transforming Earth’s natural landscapes so dramatically that as many as one million plant and animal species are now at risk of extinction, posing a dire threat to ecosystems that people all over the world depend on for their survival, a sweeping new United Nations assessment has concluded. The 1,500-page report, compiled by hundreds of international experts and based on thousands of scientific studies, is the most exhaustive look yet at the decline in biodiversity across the globe and the dangers that creates for human civilization. A

WASHINGTON — Humans are transforming Earth’s natural landscapes so dramatically that as many as one million plant and animal species are now at risk of extinction, posing a dire threat to ecosystems that people all over the world depend on for their survival, a sweeping new United Nations assessment has concluded. The 1,500-page report, compiled by hundreds of international experts and based on thousands of scientific studies, is the most exhaustive look yet at the decline in biodiversity across the globe and the dangers that creates for human civilization. A  When I was laid off in 2015, I told people about it the way any good millennial would: By tweeting it. My hope was that someone on the fringes of my social sphere would point me to potential opportunities. To my surprise, the gambit worked. Shortly after my public plea for employment, a friend of a friend sent me a Facebook message alerting me to an opening in her department. Three rounds of interviews later, this acquaintance was my boss. (She’s now one of my closest friends).

When I was laid off in 2015, I told people about it the way any good millennial would: By tweeting it. My hope was that someone on the fringes of my social sphere would point me to potential opportunities. To my surprise, the gambit worked. Shortly after my public plea for employment, a friend of a friend sent me a Facebook message alerting me to an opening in her department. Three rounds of interviews later, this acquaintance was my boss. (She’s now one of my closest friends). In the opening of The Other Americans, Laila Lalami’s fourth novel, a man is killed in a hit-and-run collision. The victim is Driss Guerraoui, an immigrant and small business owner who, after fleeing political unrest in Casablanca, eventually settles in a small town in California’s Mojave Desert to open a business and raise his family. His immigrant story is one his younger daughter Nora, a jazz composer, considers with mixed feelings. “I think he liked that story because it had the easily discernible arc of the American Dream: Immigrant Crosses Ocean, Starts a Business, Becomes a Success.” And it’s this clichéd American-immigrant narrative that Lalami sets out to deconstruct in her book.

In the opening of The Other Americans, Laila Lalami’s fourth novel, a man is killed in a hit-and-run collision. The victim is Driss Guerraoui, an immigrant and small business owner who, after fleeing political unrest in Casablanca, eventually settles in a small town in California’s Mojave Desert to open a business and raise his family. His immigrant story is one his younger daughter Nora, a jazz composer, considers with mixed feelings. “I think he liked that story because it had the easily discernible arc of the American Dream: Immigrant Crosses Ocean, Starts a Business, Becomes a Success.” And it’s this clichéd American-immigrant narrative that Lalami sets out to deconstruct in her book. This week, amid devastating

This week, amid devastating  If someone says, “I guess it’s in my DNA,” you never hear people say, “DN—what?” We all know what DNA is, or at least think we do.

If someone says, “I guess it’s in my DNA,” you never hear people say, “DN—what?” We all know what DNA is, or at least think we do. For a few months in 2008 and 2009 many people feared that the world economy was on the verge of collapse…

For a few months in 2008 and 2009 many people feared that the world economy was on the verge of collapse… Cyril Connolly once wrote: “The more books we read, the clearer it becomes that the true function of a writer is to produce a masterpiece and that no other task is of any consequence.” This is tosh, of course, for if every book were a masterpiece, no book would be a masterpiece and we could not know a masterpiece when we read it. They also serve who only sit and write trash. To know the good, we have to know the bad. The precise quantity and degree of the bad that we have to know in order to appreciate the good is debatable, and certainly there is no great difficulty in finding the bad, whether it be bad food, bad films, bad theatre productions, bad behaviour or bad books. Indeed, the only thing that can be said in favour of the current overwhelming prevalence of the bad is that it adds to the pleasure of finding the good — the piquancy both of discovery and relief.

Cyril Connolly once wrote: “The more books we read, the clearer it becomes that the true function of a writer is to produce a masterpiece and that no other task is of any consequence.” This is tosh, of course, for if every book were a masterpiece, no book would be a masterpiece and we could not know a masterpiece when we read it. They also serve who only sit and write trash. To know the good, we have to know the bad. The precise quantity and degree of the bad that we have to know in order to appreciate the good is debatable, and certainly there is no great difficulty in finding the bad, whether it be bad food, bad films, bad theatre productions, bad behaviour or bad books. Indeed, the only thing that can be said in favour of the current overwhelming prevalence of the bad is that it adds to the pleasure of finding the good — the piquancy both of discovery and relief. OVER THE PAST FEW YEARS—

OVER THE PAST FEW YEARS—