David Dobbs in The New York Times:

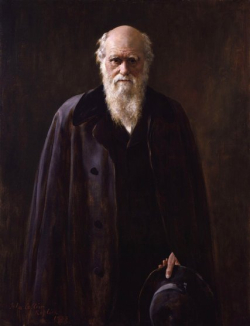

A little over a decade after he published “On the Origin of Species,” in which he described his theory of natural selection shaped by “survival of the fittest,” Darwin published another troublesome treatise — “The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relationship to Sex.” This expanded on an idea he mentioned only briefly in “Origin.” Sometimes, he proposed, in organisms that reproduce by having sex, a different kind of selection occurs: Animals choose mates that are not the fittest candidates available, but the most attractive or alluring. Sometimes, in other words, aesthetics rule. Darwin conceived this idea largely because he found natural selection could not account for the ornaments seen in many animals, especially males, all over the world — the bright buttocks and faces of many monkeys and apes; the white legs and backside of the Banteng bull, in Malaysia; the elaborate feathers and mating dances of countless birds including bee-eaters and bell-birds, nightjars, hummingbirds and herons, gaudy birds of paradise and lurid pheasants, and the peacock, that showboat, whose extravagant tail seems a survival hindrance but so pleases females that well-fanned cocks regularly win their favor. Only a consistent preference for such ornament — in many species, a “choice exerted by the female” — could select for such decoration. This sexual selection,as Darwin called it, this taste for beauty rather than brawn, constituted an evolutionary mechanism separate, independent, and sometimes contrary to natural selection. To Darwin’s dismay, many biologists rejected this theory. For one thing, Darwin’s elevation of sexual selection threatened the idea of natural selection as the one true and almighty force shaping life — a creative force powerful and concentrated enough to displace that of God. And some felt Darwin’s sexual selection gave too much power to all those females exerting choices based on beauty. As the zoologist St. George Jackson Mivart complained in an influential early review of “Descent,” “the instability of vicious feminine caprice” was too soft and slippery a force to drive something as important as evolution.

A little over a decade after he published “On the Origin of Species,” in which he described his theory of natural selection shaped by “survival of the fittest,” Darwin published another troublesome treatise — “The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relationship to Sex.” This expanded on an idea he mentioned only briefly in “Origin.” Sometimes, he proposed, in organisms that reproduce by having sex, a different kind of selection occurs: Animals choose mates that are not the fittest candidates available, but the most attractive or alluring. Sometimes, in other words, aesthetics rule. Darwin conceived this idea largely because he found natural selection could not account for the ornaments seen in many animals, especially males, all over the world — the bright buttocks and faces of many monkeys and apes; the white legs and backside of the Banteng bull, in Malaysia; the elaborate feathers and mating dances of countless birds including bee-eaters and bell-birds, nightjars, hummingbirds and herons, gaudy birds of paradise and lurid pheasants, and the peacock, that showboat, whose extravagant tail seems a survival hindrance but so pleases females that well-fanned cocks regularly win their favor. Only a consistent preference for such ornament — in many species, a “choice exerted by the female” — could select for such decoration. This sexual selection,as Darwin called it, this taste for beauty rather than brawn, constituted an evolutionary mechanism separate, independent, and sometimes contrary to natural selection. To Darwin’s dismay, many biologists rejected this theory. For one thing, Darwin’s elevation of sexual selection threatened the idea of natural selection as the one true and almighty force shaping life — a creative force powerful and concentrated enough to displace that of God. And some felt Darwin’s sexual selection gave too much power to all those females exerting choices based on beauty. As the zoologist St. George Jackson Mivart complained in an influential early review of “Descent,” “the instability of vicious feminine caprice” was too soft and slippery a force to drive something as important as evolution.

Darwin’s sexual selection theory thus failed to win the sort of victory that his theory of natural selection did. Ever since, the adaptationist, “fitness first” view of sexual selection as a subset of natural selection has dominated, driving the interpretation of most significant traits. Fancy feathers or (in humans) symmetrical faces have been cast not as instruments of sexual selection, but as “honest signals” of some greater underlying fitness. Meanwhile, the “modern synthesis” of the mid-1900s, which reconciled Darwinian evolution with Mendelian genetics, redefined evolutionary fitness itself not in terms of traits, but as the survival and spread of the individual genes that generated the traits. Genes, rather than traits, became what natural selection selected.

And so things largely remained until now. This summer, however, almost 150 years after Darwin published his sexual selection theory to mixed reception, Richard Prum, a mild-mannered ornithologist and museum curator from Yale, has published a book intended to win Darwin’s sex theory a more climactic victory. With THE EVOLUTION OF BEAUTY (Doubleday, $30), Prum, drawing on decades of study, hundreds of papers, and a lively, literate, and mischievous mind, means to prove an enriched version of Darwin’s sexual selection theory and rescue evolutionary biology from its “tedious and limiting adaptationist insistence on the ubiquitous power of natural selection.” He feels this insistence has given humankind an impoverished, even corrupted view of evolution in general, and in particular of how evolution has shaped sexual relations and human culture.

More here.

Even as machines known as “deep neural networks” have learned to converse, drive cars, beat video games and Go champions, dream, paint pictures and help make scientific discoveries, they have also confounded their human creators, who never expected so-called “deep-learning” algorithms to work so well. No underlying principle has guided the design of these learning systems, other than vague inspiration drawn from the architecture of the brain (and no one really understands how that operates either).