by Carol A Westbrook

A few weeks ago, I was sitting in a downtown doctor’s office, interviewing a potential concierge physician to see if we were compatible. I had decided it was time to make some changes in my health care, and for good reason. I’m in my 70’s, I’m handicapped, and I’m a physician, specializing in internal medicine and medical oncology. But it’s been years since I had any professional training or kept up to date. The few times I’ve ended up in an emergency room I felt insecure, I couldn’t remember how to read an EKG or a chest X-Ray! It was time for me to get another set of eyes on my health care, and find someone I could trust to oversee it. I need a primary care physician, and I’d like her to be someone whose philosophy of medical practice was similar to mine.

I had my Uber drop me at 680 N Lake Shore Drive. It was an impressive building, part of the old Northwestern Medical School. There was a lovely set of granite stairs with bronze railings, and flanking these on either side were ramps. I unfolded my walker and headed up the handicapped ramps. It was a long walk, but I made it up to the front door.

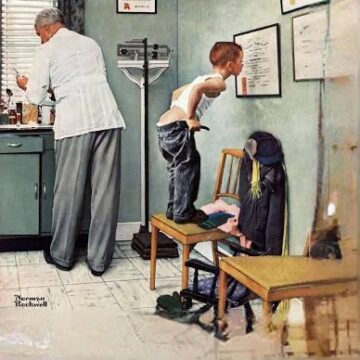

“Back in the day,” as we like to say, we practiced primary care—that is to say, adult internal medicine—differently. During my residency training at the University of Chicago we looked upon our patients as people. We knew each one—and their family—individually. The charts were reviewed before a clinic visit, and updated at the end of the encounter. We spent as much or as little time as needed. If a new problem came up for one of my patients, all it took was a call to me to set the wheels in motion. Because of our familiarity with the clinical history, we were more prepared to deal with emergencies as they came up. If there was a problem outside of my area of expertise, I could easily arrange a referral or transfer to the appropriate speciality. In this way, lines of communication remained open and we provided the best of care to our patients, without having to assign them to another doctor or nurse specialist at the end of the shift.

This is the way Primary Care medicine should be practiced, but this model no longer exists, and the reason is straightforward—it is too expensive to provide this amount of time and individual attention for the number of patients that a primary care doctor is expected to see in the current medical climate.

Dissatisfaction with current medical practice led some doctors to explore alternative ways of providing care. One successful model was the concierge practice, named for the concierge type of personal care used by hotels. As you know, a hotel concierge provides personalized care to hotel guests, such as making dinner reservations or show tickets. The first such medical concierge establishment was called MD2with offices in Washington state and Oregon. They began in 1996 by charging an annual retainer fee of $13,200 for individuals and $20,200 for families. The plan was to provide individualized care for patient and families, so they would get seen quickly for new problems, recognizing that these were people with busy lives, who had more money than time.

In a theoretical “back of the envelope” calculation, you can see that running a practice with a limit of 300 patients, each of whom paid for $4,000 per year, will bring in about $1,200,000,half of which could be used to support the practice – staff salaries, lab costs, office rental and so on. Having 3 or 4 docs share the office would provide additional support if needed. It should be easy for a doc to keep track of 300 patients—about the size of a typical high school graduating class.

What does the concierge patient get for her $4,000? A yearly physical exam—or more if needed. Laboratory work, immunizations and so on; follow-up calls as needed and, most important, access. Any unusual symptoms, cough, headache, etc – your doctor is just a phone call away and can see you that day or the next at the very latest. This is the very personalized care of the kind your family may have had when you were a child.

This is the kind of primary care that everyone should have, but our health care spending will not be able to support. In 2019, the national trade publication Concierge Medicine Today estimated that 12,000 out of about one million licensed physicians in the US were engaged in concierge medicine; average monthly membership fees were between $135 and $150.

There are benefits to the concierge physician.

Doctors in these practices said the fees brought in predictable revenue and guaranteed them a minimum annual income. Furthermore, the patient caseload of a concierge physician was about 80 to 90 percent smaller, which gave doctors more time to devote to each patient. Consumer Reports stated in 2018 that primary care physicians on average saw a patient 1.6 times a year and spent fifteen minutes in each patient visit. The average visit with a concierge primary care physician was thirty-five minutes, while concierge doctors provide 35-minute, or often 30 to 60-minute, appointments, which allows for more in-depth, personalized, and unhurried care.

Patient Load: Traditional primary care practices often manage 1,000 to 2,000+ patients, while concierge practices often limit their panels to 600 patients or less. Access: Concierge/DPC doctors often allow for same-day appointments, direct access via phone/email, and minimal wait times.

I talked with a few doctors about why they chose a concierge practice, and almost all felt that the current medical climate was too demanding and did not make it possible for them to take care of their patients when they were sick. In other words, treating paatients was no longer fun and gratifying. A few concierge docs felt that they wanted to limit their practice to longevity, or to manage wellness, but these were in the minority.

In a few days I heard back from the concierge practice I had been interviewing. They decided against accepting me into their patient panels. The reason: I was too handicapped and could not make it easily into their offices; they were concerned that I might have an accident. I thought this was ironic, since a health care facility is supposed to be a place of safety. But I will continue to look for the right practice to accommodate me and my walker.