by Jim Hanas

Any sufficiently advanced technology might be indistinguishable from magic, as Arthur C. Clarke said, but even small advances–if well-placed–can seem miraculous. I remember the first time I took an Uber, after years of fumbling in the backs of yellow cabs with balled up bills and misplaced credit cards. The driver stopped at my destination. “What happens now?” I asked. His answer surprised and delighted me. “You get out,” he said.

Any sufficiently advanced technology might be indistinguishable from magic, as Arthur C. Clarke said, but even small advances–if well-placed–can seem miraculous. I remember the first time I took an Uber, after years of fumbling in the backs of yellow cabs with balled up bills and misplaced credit cards. The driver stopped at my destination. “What happens now?” I asked. His answer surprised and delighted me. “You get out,” he said.

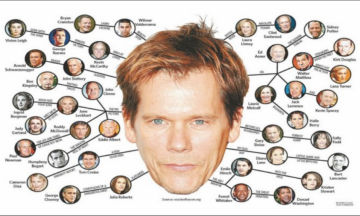

Thirty years ago a website appeared that, in the early days of “the graphical portion of the Internet”–as the New York Times then faithfully called the World Wide Web upon first occurrence–seemed like such a miracle. I am speaking, of course, of the Oracle of Bacon, the site inspired by the parlor game “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon.” The story of the Oracle, which is maintained to this day, is–in many ways–the history of the consumer Internet in brief. It features a meme, virality, consumer delight, and unintended consequences–but more on those later.

The Oracle is based on a game invented by college students in 1994. An early message board thread titled “Kevin Bacon is the Center of the Universe” challenged readers to find the shortest path between Kevin Bacon and other actors via chains of movies they had appeared in together. The post reported that the game’s initial prompt had “received 80 responses in just over a week” (!) at the University of Virginia, though it was three students at Albright College in Pennsylvania that codified the game–and its benchmark–under the name “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon,” after the 1993 movie based on the John Guare play of the same name. A book followed in 1996, and–were it not for the contemporaneous explosion of the World Wide Web–the story might have ended there.

Instead we turn back to the University of Virginia and the launch of the Oracle, that same year, by a team led by then-Ph.D student Brett Tjaden. Instead of having to play the game, the Oracle showed you the shortest path between Kevin Bacon and any other actor. The Oracle spread like wildfire as people huddled around their crazy-slow dial-up connections to try to find an actor with “Bacon Number”–based on the (presumably) more prestigious Erdős Number–greater than 6. Those who were successful had their names added to The Oracle of Bacon Hall of Fame, which stopped taking entries in 2001. Part of the site’s virality certainly had to do with pure technical novelty. As Patrick Reynolds, who has maintained the Oracle since 1999, told me this week via email:

“I think the Oracle of Bacon was an early example of dynamic web content, or web content backed by a database of any kind. In 1996, most of the web was static HTML plus a few search engines. Search engines were and are dynamic content, but their purpose then was to help you find static content. The Oracle was an early example of the idea that a web server could do some computation on behalf of a user’s query and present a web page specific to that user and that moment in time.”

Pretty nifty at the time. But another aspect of the Oracle’s appeal were the results themselves. That it could find the shortest path and that the path was routinely so low–the average Bacon Number is 3.1–was surprising to the average user, creating the sensation that there was something special about Mr. Bacon. There isn’t, of course, and the Oracle’s dataset was used to demonstrate why.

The intuition that we are more closely connected than we might think–that it is “a small world after all”–may be modern, but it is not new. The 1929 short story “Chains” by the Hungarian writer Frigyes Karinthy presents a game very much like “Six Degrees”–though the bet is that any two people on earth can be connected in five steps–and the existential sense that “Planet Earth has never been as tiny as it is now.” Stanley Milgram himself sought to validate this hunch via the postal service in the 1960s and found that random individuals could find each other through acquaintances in between five and six links. Finally, in 1998, Duncan J. Watts and Steven H. Strogatz published an influential article in Nature in which they articulated how to construct–and the essential characteristics of–so-called “small-world” networks, which relied in part on data from the Oracle. As Watts writes in his 2003 book Six Degrees, “The result was clear. … In a world consisting of hundreds of thousands of individuals, every actor could be connected to every other actor in an average of less than four steps.” (Emphasis in original.)

The world had gotten even smaller than Karinthy thought, but in a non-intuitive way that Watts and Strogatz were able to articulate. In short, it takes very few random connections in a large population to dramatically decrease the distance between members, and there is a sweet spot between order and randomness where members will be highly clustered. And if these members happen to be people–they need not be, since small-world network effects can be found elsewhere–the phenomenology of being in such a network is somewhat curious. A tiny bit miraculous, if you will. As Watts observes, “individuals located somewhere in a small-world network cannot tell what kind of network they’re living in–they just see themselves as living in a tight cluster of individuals who know one another.” An impression created not by order, but by the right amount of randomness.

Thirty years later, it is not hard to see how this impression has played out, as common sense expectations have collided with collapsing path lengths and high clustering coefficients. What are the chances that clammy hands and dry eyes will return a meaningful search result? Much higher than you’d think, though that doesn’t mean there is anything intrinsic about their association. What are the chances that two public figures–or political leaders, or donors–are associated in some way? Also much better than you’d think, because (again) there is nothing special about Kevin Bacon.

Early users of the Oracle were not, in fact, having an experience that contained much information about Kevin Bacon. As of last month, there are 506 actors that generate lower average path lengths than he does. Rather, they were experiencing the surprising properties of small-world networks without being fully aware that that was what they were experiencing.

The Oracle was an early example of dynamic web technology applied to a problem other than search, as Reynolds says, but this suggests another way of looking at it. Aren’t search engines–and their AI successors–just general purpose Oracles, capable of creating the same small-world sensations at massive scale? It seems no accident that the last thirty years have seen a rise in argumentation based on adjacency–from Rachel Maddow’s suggestive lead-ins to Hillary Clinton’s much-hyped proximity to Uranium One–as search engines deliver the shortest past between almost any two “actors” on demand. (Which is not to say that things do not have causal or corrupt connections; just that adjacencies are frequently insufficient to demonstrate them. That is the job of reporting.)

At the extremes, this lends itself to conspiracy theories like QAnon and Pizzagate, the popularity of which are often attributed to apophenia, among other factors. Apophenia is the tendency to perceive connections between unrelated phenomena, but the phenomenology of the Oracle suggests that a more subtle error is at play in conspiratorial thinking. Specifically, it involves mistaking one type of connection for another–network properties for real-world relationships. Kevin Bacon might not be special, but his name is on the game.

It also casts doubt on the usefulness of apophenia as a concept, as stated, since–in networks–there are no such things as “unrelated phenomena.” Everything is connected to everything else, in at least one sense, and more closely than you might expect.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.