by Malcolm Murray

Back when I worked for large corporations, people would often talk of being in “period of change” or how they could “see the light at the end of the tunnel” after a period of heavy restructuring or similar. These days, you might be forgiven for wondering where the tunnel went. Change is incessant and showing no signs of slowing down. In fact, it is quite the opposite. We are entering a period when change might in fact actually be speeding up, even from its currently historically high levels. While not the majority view, nor the most likely scenario in my estimation, there is still a nonzero likelihood that we are in fact in the last few years of an era. Through the development of AGI – artificial general intelligence – the world could become unrecognizable in just a few years.

Back when I worked for large corporations, people would often talk of being in “period of change” or how they could “see the light at the end of the tunnel” after a period of heavy restructuring or similar. These days, you might be forgiven for wondering where the tunnel went. Change is incessant and showing no signs of slowing down. In fact, it is quite the opposite. We are entering a period when change might in fact actually be speeding up, even from its currently historically high levels. While not the majority view, nor the most likely scenario in my estimation, there is still a nonzero likelihood that we are in fact in the last few years of an era. Through the development of AGI – artificial general intelligence – the world could become unrecognizable in just a few years.

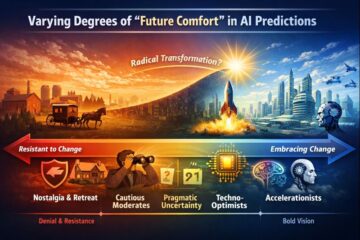

In a recent Astral Codex Ten piece, Scott Alexander referenced several examples of people seeing the clock as ticking down to a near-term singularity-level change, which would leave permanent patterns locked in. In one of the most talked-about AI forecasts from last year – AI 2027 – 2026 is not far from where the hockey stick starts to get seriously steep. This scenario, of humanity facing a potential precipice in our near future, makes for an interesting exercise in examining the varying levels of comfort people have in entertaining this possibility. We can name it “Future Comfort”. The degree to which people accept this possibility, fight against it, deny it, or even embrace it. Especially now at the turning of the year, with everyone making predictions, this seems like a useful lens for examining the world right now.

Let’s first look at the varying schools on the Future Comfort spectrum. On one far end, we have people who are deeply uncomfortable with this notion. They are actively fighting against the future and are actively and quixotically trying to bring back the past. We have seen this in some of the main political strands over the past years, driving everything from Brexit to MAGA to Soviet nostalgia. A little bit towards the center of the spectrum, instead of active resistance, you could place the groups exercising passive resistance. This would include people choosing to go “off the grid” or “back to nature” or other variants of the Amish lifestyle.

On the other far end of the spectrum, we have those who are deeply comfortable with a radically different future. Here, we find groups such as transhumanists and effective accelerationists. They are looking to bring the future closer, not further and long to merge with the machine, becoming cyborgs. Moving slightly toward the center, we find the libertarian techno-optimists such as Marc Andreesen, who want to let technology rip loose, in a wild Schumpeterian dance of creative destruction. It would be easy to dismiss these end points as fringe fanatics, were it not for the fact that they win elections in major Western democracies and have their own Super PACs with millions of funding.

Turning then to the AI commentariat, which at least mostly sits between these two endpoints, we also see striking differences in the willingness to engage with this kind of “Future Shock”, as Toffler called it. In AI regulation, we saw a striking example of the “stick-your-head-in-the-sand” crowd in the form of a recent open letter from hundreds of scientists to the European Commission. Again, the prevailing sentiment seems to be that even considering the idea that advanced AI might lead to significant changes is anathema.

We also see this among my forecasting peers. They also cluster in distinct groups based on different levels of willingness to engage with the however small possibility that we might soon enter a new era. The announcement of the first set of results from LEAP (Longitudinal Expert AI Panel), a forecasting study that I am part of, demonstrated this well. Experts fall in-between the gung-ho “predictions” of AI company leaders and the views of the general public, but also fall into distinct clusters with very different probabilities for any kind of change to the status quo.

In recent 2026 AI prediction newsletters, we can see these differences clearly. Some writers, such as those in Transformer, appear relatively comfortable entertaining the possibility of near-term, era-level change, even if they assign it modest probabilities. Others, such as Understanding AI, occupy a more ambivalent middle ground — acknowledging acceleration while emphasizing continuity and constraint. At the other end, skeptics like Gary Marcus show markedly lower “future comfort,” treating the very idea of discontinuous change as something to be resisted rather than explored.

No one can know what the future actually holds. In my mind, both the scenario that AI progress hits roadblocks and peters out at current levels (which would still lead to massive changes in society, but not to an unrecognizable world) and the scenario with continued exponential progress and self-recursive improvement are potential scenarios to consider and give nonzero probabilities of occurring. Further, given the scale of change in the latter scenario, the precautionary principle behooves us to at least entertain the possibility of that change and prepare for it. “Future Comfort”, which importantly is not about optimism or pessimism, but about the psychological and intellectual willingness to reason seriously about discontinuous change, might become one of the dominating traits of success in coming years.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.