by Lei Wang

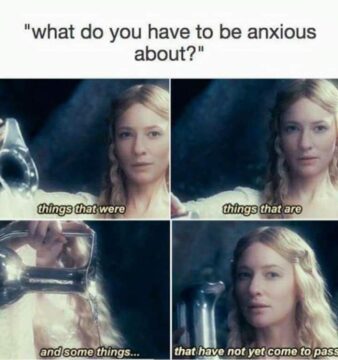

The world is scary right now. I know this to be true, and yet from 14 years of meditation exposure I also know to ask: is it scary… here and now? Here, where I’m writing, in the library of the campus music building, with its floor-to-ceiling glass windows overlooking a Zen garden (there was a big donor a while back), surrounded by books on the loves of Mozart and the many intricacies of the art of singing?

In Beyond Anxiety, sociologist and self-help author Martha Beck said she became free of anxiety once she realized most of her fears were based on things that were not actually in the room with her—things that were imagined. In an interview with Big Think, she said, “I remember one time, terrible things were happening in the world, as they always are, and I was sitting in meditation. I thought, ‘How could I be expected to feel calm under these circumstances?’ Another part of me said, ‘You mean the circumstances of your bedroom?’”

It’s true: my bedroom, my café, my music library is not in Minneapolis, or Gaza, or Tehran. The predator is not in the room with me. The predator is imagined, and yet at the same time, it is very real. In “A Brief for the Defense,” the poet Jack Gilbert writes:

Sorrow everywhere. Slaughter everywhere. If babies

are not starving someplace, they are starving

somewhere else. With flies in their nostrils.

But we enjoy our lives because that’s what God wants.

I’ve attended several world peace group meditations over the last few weeks: to transform human ego consciousness, to send love to all beings—is this what God wants? Is this how I can best use my time and life? I keep writing my book, on spiritual enlightenment, which I genuinely think can help people. And yet. I’ve somehow hung out with many people who quite literally feel they are not separate from any other being in the world, but they are not necessarily activists. And this makes sense: just because we identify with our bodies doesn’t mean we always treat our bodies nicely. We presumably are one with our livers, and yet we continue to drink. Being one with everything doesn’t mean you will or can be responsible for that everything. And perhaps it means being one with the oppressor as well as the oppressed.

I have always said I liked the timeless over the timely: meditation and poetry over, say, wellness trends, the news. A college classmate has been running the Jerusalem Youth Chorus for years, bringing Israel and Palestinian teenagers to sing together, even now. These are his seeds of peace. The world doesn’t need my anxiety, but does it need my bubble of relative okayness? Does it need my book, my meditation, my joy right now? Perhaps these are not the right questions.

Later in Jack Gilbert’s poem: “If we deny our happiness, resist our satisfaction, we lessen the importance of their deprivation.” And: “We must have the stubbornness to accept our gladness in the ruthless furnace of this world.”

Liz Gilbert (no relation to Jack) relates a story in Eat, Pray, Love about her friend, Deborah the psychologist, who was asked to offer counseling to a group of Cambodian refugees—boat people—who had then recently arrived in 1980s Philadelphia, escaping genocide. Deborah felt terribly underequipped to help them. But what did these refugees want to talk to her about once they could see a therapist? “It was all: I met this guy when I was living in the refugee camp, and we fell in love. I thought he really loved me, but then we were separated on different boats, and he took up with my cousin. Now he’s married to her, but he says he really loves me, and he keeps calling me, and I know I should tell him to go away, but I still love him and I can’t stop thinking about him. And I don’t know what to do…”

“This is what we are like,” writes Gilbert. Maslow’s pyramid has always emphasized the heirarchies of survival—body first, then the softer emotions—but in reality, it’s often the full pyramid, all at once. Much is made of how Quartet for the End of Time, by French composer Olivier Messiaen, was written and performed in a prisoner of war camp in Germany in 1941. Jack Gilbert again: “We must admit there will be music despite everything.” But the music also required a sympathetic anti-Nazi guard, a guard who loved music and who gave Messiaen, paper, pencil, and protected time, and later helped him escape. (Were the non-musicians less deserving?) Even sans electricity, a violinist in Gaza may be listening to symphonies in her head right now, and they are all the more precious for their deprivation.

I used to think meditation could solve all problems. Certainly it can bring the end of a particular kind of modern neuroticism, the anxious, grasping self-narrative/“please like me” orientation towards the world (which I’m still working on). Certainly enlightened saints have also worked for the good of the world, in high-performance peace.

All I wanted when I started the spiritual path was just to make living a little more bearable, and it has mostly worked. I have not been depressed in over a decade. I have gotten quite good at reducing my personal suffering, at solving the problems that can be solved with meditation. But lately I have been wondering within my little peace prison if saying “meditate” to emotional turbulence in these times is like Marie Antoinette saying, “Let them eat cake.” Necessary, but not sufficient. The therapist Irving Yalom used to say, of therapy, “Strike when the iron is cold.” Therapy doesn’t work as well when the client is actively triggered. Meditation is also very useful when the iron is cold, but what about when the iron is hot?

May we live in less interesting times.

“Anyone scrolling a social media platform can be instantaneously invited to care about more human suffering than the greatest saints in history would have encountered over the course of their whole lives,” writes Oliver Burkeman in Meditations for Mortals, a book on embracing limitations, in a section called “On staying sane when the world’s a mess.” Saints had a few primary causes, he says, they took care of the human suffering that showed up in front of their faces from day to day, while today, with technology, “assuming you’re the kind of person who considers it your duty to care about anything beyond the walls of your home, you’re liable to be asked to care, with maximum intensity, about everything.” Burkeman’s solution? Pick your battles, and don’t feel bad about that.

There is part of me that just wants to send healing to people doing their jobs, even if that job happens to be working for ICE. May they too be safe and happy. May they not feel the whole world, or half the country, is against them, even if we think one half is totally wrong. Even if we think the other half is, as Hillary Clinton called Trump voters in 2016, “a basket of deplorables.” I can imagine myself as one of these deplorables. I probably would not have been immune, if I had grown up differently, if various circumstances had or hadn’t found their way into my life. I would not want anyone to think I am deplorable. I would think, in my own mind prison, that I was doing the good thing.

In an old episode of Radiolab called “The Bad Show,” self-described as “a show about the little bit of bad that’s in all of us… and the little bit of really, really bad that’s in some of us,” they revisit the Stanley Milgram experiments at Yale. This is the study where participants were asked to administer electric shocks to a human in another room if that person got answers to questions wrong, steadily increasing the voltage until the other person pleaded to be let off the hook, citing danger to their lives. Unbeknownst to them, the person being shocked in the other room was only an actor. 65% of participants were willing to shock people to the maximum level, 450 volts. A large part of the experiments was about the researcher in the room goading the participants to administer higher and higher levels of shock, saying it was necessary for the study. But whenever it got to the point where the researcher gave an absolute order to the participant, saying “you have no choice: you must continue,” the participant would rebel against the command. They didn’t want to shock someone simply because they had to.

“So you’re saying they’re shocking these people because they think it’s worthwhile?” the radio broadcasters say. The expert they’re interviewing replies, “They’re engaged with the task, they’re trying to be good participants, trying to do the right thing. They’re not doing something because they have to, they’re doing something because they want to, and that’s all the difference in the world.”

The writer T Kira Madden has a writing exercise in which you write a rant against someone in the world you want to rant against: a specific person, a public figure. Then you find a picture of that person and look into their pixelated eyes for three minutes. And continue writing your rant.

Because I am not otherwise a saint, I feel it is a failing in me that I can’t seem to muster much of a rant. I once went to a workshop on emotions in which, on their nametag, everyone had to write an emotion they wanted to embody more of. “Lei / Anger,” I wrote on mine, meaning the righteous kind. Anger and heartbreak and anxiety and depression seem to be the rational response right now. Is anything else the beginnings of not evil, but apathy?

There are studies showing empathy, which is more felt and embodied and takes on the suffering of the other (feeling with someone), can not be sustained as long as compassion, which is more abstract (feeling for someone). True empathy requires more one-on-one detail and imagination, while compassion can work on a general basis: one can be compassionate for all humanity, all murderers, even. But it is much more difficult to be empathetic with all beings.

“May all beings be happy…” Is this a form of anesthesization? The way self-help really took off as an industry in the 1980s, just as unions were winding down and the ideology of the individual arose. A friend’s partner’s philosophy PhD thesis (as far as I can understand) is on the ethics of therapy: other than helping people feel good, what is therapy really for? Are therapists responsible for creating people who not just search for that elusive sense of personal well-being, but also how to create well-being in the world?

I have been learning all these years “to surrender,” as the spiritual parlance goes, to not control what I can’t control, but am I learning to be passive?

“Tell me,” an anarchist lover asked me once, very seriously, “Do you just wanna grill?”

Jack Gilbert’s poem, arguing for joy despite, is called “A Brief for the Defense.” Who is the prosecutor, I wonder?

Years ago, when I was overwhelmed and didn’t want to live at all, it was not so much that I wanted to die as I wanted to be pure consciousness. But now I want to be a mystic who lives in the world. I wish someone could tell me my particular role in the world, if I can just write my little books, teach meditation (perhaps to those who need it the most who have access to it the least), but maybe wanting someone to tell me my purpose precludes me from making a greater one of my own.

When the time comes, may I blow some whistles. May I find righteous anger and act on it. Let me move not just my mind, but my arms and legs and mouth. Let me help others find composure enough to compose. And I still want my small comforts. To make yellow curry, write in beautiful libraries, go to my Jungian Zooms, while I can. While elsewhere: flies in nostrils and the beginnings of evil. I want to believe, somewhere beyond the end of time, we will all come to terms with having done horrible things to each other, and what it was all for.

The scarier thing is no reason for evil at all, the scariest that we are all part of it.

And still I want to trust Meister Eckhart: “It is a lie, any talk of God that does not comfort you.”

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.