by Rafaël Newman

At the end of each of the past twelve years I have written a long rhyming ballad, reviewing the period coming to a close, giving thanks for some events and lamenting others. I began in December 2013, while I was recovering from a lengthy illness; and I recited what would be the first of a series at a family New Year’s Eve party, among some of those whose support had been indispensable to the recrudescence of my health, and to whom I therefore wished to express my gratitude.

At the end of each of the past twelve years I have written a long rhyming ballad, reviewing the period coming to a close, giving thanks for some events and lamenting others. I began in December 2013, while I was recovering from a lengthy illness; and I recited what would be the first of a series at a family New Year’s Eve party, among some of those whose support had been indispensable to the recrudescence of my health, and to whom I therefore wished to express my gratitude.

My poem began that year with these lines:

Let’s raise a glass this festive day,

On Saint-Sylvestre or Hogmanay,

And toast to all both far and near

Who graced the now departing year:

To cracksource Cook, who nearly gotcha,

To Edward Snowden in his dacha;

To Granta, Guardian and Gawker,

To David Denby, and Tom Scocca;

To Pauline Marois, our own Grand Mufti,

As well as Josh and Benny Safdie;

To Edie Windsor, Stephen Fry,

And Malala Yousafzai;

Barack Hussein—“Make Drones, Not War!”—

Dan Savage, and the myriad score

Who hailed with glee, or rising gorge,

The birth of Once and Future George.

This initial ode to a year gone by, following its “public” proem, then went on to become more private in substance—with cryptic tributes to the various attainments of my assembled kinfolk—for all that it borrowed its tone and humor from “Greetings, Friends!”, the Christmas poem written every year for many decades by Roger Angell and published annually in The New Yorker. Angell, better known as a baseball reporter, would compose his retrospectives as jokey commentaries on notable happenings in the public sphere; they featured sometimes quite ingenious (if often groan-worthy) rhymes on topical celebrity names, for which he evidently required increasing guidance from younger advisers as he grew more venerable (he died in 2022 at over a hundred) and less plugged in.

Angell’s 1992 poem, for instance, includes the following stanza (and no shade if you have to Google any of the early-nineties names he checks):

Here’s where warm hearts grow rife or rifer,

Near Donna Tartt and Michelle Pfeiffer,

With B. B. King and his Lucille,

And Dee Dee Meyers and Brian Friel!

Airborne with Kristi Yamaguchi,

Rip Torn, John Zorn, Maria Tucci,

Around the floor we’ll dip and cruise

With Madonna and Naguib Mahfouz.

My own 2013 roundup, presented live in Kingston, Ontario, was comparably contrived, although with extra Canadian content. But my ambitions—or perhaps pretensions—, if at the time still veiled, were more exalted: in subsequent editions of what was, for the next few years, a regular feature at family gatherings, I began to aspire to the occasional verse of W.H. Auden, not known for annual retrospectives but whose “Metalogue to The Magic Flute: Lines composed in commemoration of the Mozart Bicentenary, 1956. To be spoken by the singer playing the role of Sarastro” is a model of erudition married to ornament:

Relax, Maestro, put your baton down;

Only the fogiest of the old will frown

If you the trials of the Prince prorogue

To let Sarastro speak this Metalogue,

A form acceptable to us, although

Unclassed by Aristotle or Boileau.

No modern audience finds it incorrect,

For interruption is what we expect

Since that new god, the Paid Announcer, rose,

Who with his quasi-Ossianic prose

Cuts in upon the lovers, halts the band,

To name a sponsor or to praise a brand.

A virtually unattainable, if worthy goal. Omne tulit punctum qui miscuit utile dulci, after all.

With my newly elevated tone, there arose in years following a desire to provide opinion also on events beyond the family circle. In 2014, for example, I commented on a move by modern-day Spain to apologize for its Catholic monarchy’s 15th-century expulsion of Jewish Spaniards by offering Spanish citizenship to their returnee descendants, against the backdrop of the IDF’s response to Hamas and the intifada:

There were welcome noises, ‘mid critique

And calls for Israel’s other cheek,

From Old Castile to Sfaradeem:

“Come back and live the Spanish Dream!”

Since in Fourteen-Hundred & Ninety-Two,

The wolfish Spaniard chased the Jew;

While in Two-Naught‑Fourteen, sheepish Spain

Would love to have him back again…

In 2015, riffing on “A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning,” John Donne’s celebrated poem consoling his lover on their parting, I titled my toast “A Valediction: Permitting Mourning,” in honor of the year’s inordinate number of massacres (not suspecting how many more were to come):

Amid the general malaise

We did what one does, nowadays:

We all were Charlie, Bataclan,

Beirut, Palmyra, Kurdistan,

San Bernardino, Ferguson—

He murders all who murders one!

And nonetheless, the brutes prevailed,

In uniform and boots, or veiled

And buttressed by a shop-worn creed

That nourishes as children bleed.

In December 2016 I recorded the recent election of a certain Once and Future US President, declining to mention him explicitly but allowing his name to echo in a passage of rhymes on “dump,” noting: “It’s small I know, but, absit omen, / I’ll only rhyme, not write, his nomen.” Then, the following year, I honored resistance to the forces of reaction unleashed by that election. In 2018, in addition to fond recognition of my loved ones’ contributions to human development, I used the frame narrative of Belshazzar to “weigh up” the year’s other notable events; and, in 2019, the last year in which I performed my poem live (that is, by way of Zoom) for my family in Canada, I devoted the entirety of the piece to an allegory of climate change derived from the fairy tale of Hansel and Gretel:

So we too, in our warming world,

Amid the cakes and candies curled

On which we’ve battened, in the oven

Now tended by a ghastly coven

Of rogue confectioners and chancers,

Of narrow-minded necromancers;

By champions of vile combustion,

Adepts of fakery and fustian –

So we too need deliverance

From dangerous indifference

Anent the cause of this malaise,

Id est: our very homemade blaze!

Personal tribute was confined to a detachable epilogue, which mourned the death, that year, of a beloved family member. Detachable because, the very next day, I submitted the body of the poem for its consideration to a literary journal—alas, in vain: for all that, in my presumption, I supposed my verse was ready for a wider readership.

The next December 31, therefore, in 2020, and in each of the four years following that fateful twelvemonth, I resorted to samizdat, “publishing” my annual toasts here, on 3 Quarks Daily. Their themes have been increasingly expansive, their allegories farther-reaching: My 2020 retrospective recast the progress of COVID-19 as a flight from burning Troy; in 2021 I drew the development of a vaccination against the coronavirus in terms borrowed from the creation myth; in 2022 I decried the depredations of a range of dictators as an emanation of monotheism; in 2023 I figured the continuing willingness of “leaders” to send “their people” into battle as a version of the Binding of Isaac; and in 2024 I compared the contemporary round of saber-rattling and actual warmongering by lone, protectively isolated demagogues to the behavior of monarchs during the 19th-century Battle of Solferino, the last such European conflict in which the heads of state of the powers confronting one another led their troops personally onto the field of war.

And now it’s time for the 2025 edition of my annual poem, what would be my thirteenth. And I am paralysed. The deadline for posting my monthly submission is approaching, and all I have composed is the following:

What craven, atavistic drive

Obliges us to owe our lives

Incessantly to single bosses,

Despite their history of losses?

What dreary, self-destructive impulse

Inveigles us to sip the simples

Such sham apothecaries flog,

Part psychopomp, part demagogue?

My valediction has typically ranged between 100 and 200 lines long, so these eight iambic tetrameters are not much of a start. In addition, the theme is hackneyed, self-cannibalizing: the perils of humankind’s baleful bestowal of sovereignty on lone male leaders was, after all, implicit in my toasts to 2022, 2023, and 2024.

The pressure of external expectation, especially from a respected authority figure, can usually be counted on to force me into production; but even my usual reminder email this past Tuesday from Abbas Raza, the editor of the aggregator site for which I have written since 2019—“You are scheduled to appear on 3QD this coming Monday, the 29th of December”—has failed to galvanize me.

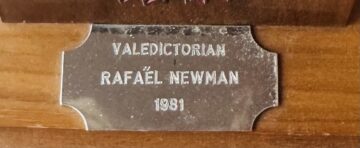

There was a time when it was otherwise, when a valediction could be jumpstarted out of me at the last minute. In late 1981 I returned to Jarvis Collegiate Institute, the Toronto high school from which I had graduated that spring, for commencement exercises. The grade 13 class that left JCI at the end of the previous academic year was invited back to welcome the incoming students, and to present an encouraging prospect to the school at large. There would be speeches by the faculty and a musical interlude. And there was to be an address by a member of the graduated class, a so-called valedictorian. I was accompanied that evening by my parents and siblings, and as we took our places in the auditorium, my father opened his copy of the printed program that had been left on each seat and exclaimed: “Hey, you didn’t tell me that YOU were the valedictorian!”

In fact, I hadn’t told anyone—because I hadn’t known myself until that moment.

I rose and approached the master of ceremonies, an English teacher; he immediately escorted me to the principal of the school, Anne Shilton, who realized, with horror, that the letter announcing my election that past summer had somehow never been posted. We had arrived early for the exercises, the valedictorian was not due to appear until halfway through, so Ms Shilton asked me whether I would consent to drafting my address then and there. I agreed.

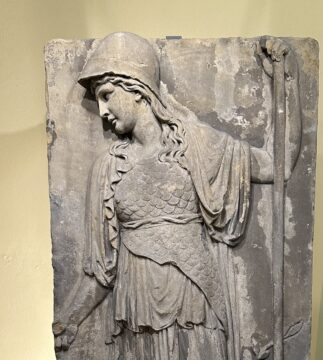

Thus, for the next 45 minutes, I was sequestered in the principal’s office with a pen and several sheets of foolscap paper. In this oddly honorable form of detention, it did not take me long to find my theme. Since I had embarked that September, just two months earlier, on a Bachelor’s degree in Classics at the University of Toronto, and was currently reading Greek tragedy with Desmond Conacher at Trinity College, my head was happily filled with sententious phrases. Just that week we had been studying Prometheus Bound, by Aeschylus, on which Professor Conacher had published a monograph the year before; and that evening my youthful powers of memorization allowed me, under duress, to produce a particular distich as an illustrative epigraph, for citation in the ancient Greek, and to gloss it in my own improvised translation:

φέρε, πῶς χάρις ἁ χάρις, ὦ φίλος;

εἰπέ, ποῦ τις ἀλκά; τίς ἐφαμερίων ἄρηξις;

“Tell me, friend,” sings the chorus to the Titan Prometheus, who has been chained to a rock and is doomed to have his ever-regenerating liver eaten out daily by an eagle as punishment for stealing the crafts of civilization from the eternal Olympians and granting them to ephemeral mortals, “what thanks have you received for your gift? What aid have you received from these creatures of a day?”

I have since mislaid my handwritten speech, and there were no cellphone recordings in 1981, so I can no longer be certain, but I suppose I may have intended the lines as a self-deprecating comment on my own overweening hubris, preaching to the assembled Titans at such an early stage of my education, still a truly ephemeral creature myself; or perhaps I was ironically casting myself as Prometheus, imprisoned in the office of the principal (AKA Zeus), commanded to expose my innards to the ephemeral creatures in the auditorium and unable to expect any aid from that quarter. In the event the speech was well received: mainly, no doubt, because I was able to turn my grim epigraph, whatever its latent significance, into a manifest vote of thanks for the gift we graduates had received from our Promethean teachers at JCI, chained to their own rock of institutional duty: the gift of wisdom.

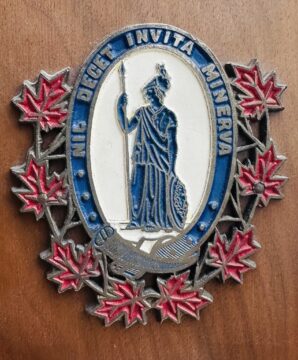

Such a gift had been implicitly promised to its students by the school, founded at the turn of the 19th century and led in the ensuing decades by the redoubtable Bishop John Strachan. Jarvis Collegiate Institute’s motto is Nil decet invita Minerva—“Nothing is seemly save by agreement of Athena.” In other words, the Goddess of Wisdom must grant her approval to an undertaking as a guarantee of its ethical fitness.

Such a gift had been implicitly promised to its students by the school, founded at the turn of the 19th century and led in the ensuing decades by the redoubtable Bishop John Strachan. Jarvis Collegiate Institute’s motto is Nil decet invita Minerva—“Nothing is seemly save by agreement of Athena.” In other words, the Goddess of Wisdom must grant her approval to an undertaking as a guarantee of its ethical fitness.

That gift—the approval of the Goddess of Wisdom—is what I am missing this December, amid the general bleakness of a world in which massacres no longer occasion outrage but are accepted as the price of a geopolitics grown unapologetically exterminationist.

When I was beginning my recovery from illness in 2013, as I composed the first of my 12 annual valedictions, I had learned to say a mantra. It is a prayer, in fact, although it would be a while before I could allow my atheist self to acknowledge it, and to recite it, as such:

God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.

In past years, evidently, I have been guided by Reinhold Niebuhr’s renowned formulation: I have somehow managed in verse to express my indignation at the world around me, my impotence in the face of its inequities consoled by the sense that such expression constituted an action on my part, however microscopic; that this action could effect a tiny change; and that my serene discernment of the difference between acceptance and courageous change was due to the gift of wisdom.

This year, it seems, rather than forbidding mourning, my valediction has itself been forbidden: by my mourning the world in which we are becoming all too much at home, and in which serenity, courage, and especially the gift of wisdom seem all too distant hopes. But I shall continue to beseech the Goddess, and to wish us all a more serene, a more courageous, and above all a wiser 2026, a year in which Minerva approves the ethical fitness of our undertakings.