by Dilip D’Souza

Allow a columnist his anguish, because what follows is almost all I have been able to think about for several days now.

Years ago, a college mate jumped into a well.

Well, in truth that’s a little bit of an exaggeration. He and I knew each other because we were partners on some lab assignments in some early electronics course. But we were not really close friends. But then he jumped into that well, and for a long time afterward, he was on my mind far more than any of my much closer college buddies were.

Because, of course, that day he took his own life. He left an entire college campus simply devastated. Through my years on that campus, we had a few suicides – but for some reason, it was what this particular young man did that stayed on in my mind. I remember lying awake nights, sitting through lectures, nursing cups of coffee … agonizing over him through all that, through everything in my daily routine.

Had he been thinking of taking his life the last time we had met, in the lab? If so, were there signs I might have, could have, should have, picked up on? If so, what if I had just asked, quietly, “Wanna talk?” What were his thoughts in those moments before he jumped? Did he survive for any length of time? If so, what was he thinking, lying there alive at the bottom of the well?

Questions, questions. None came with any answers, of course. But for weeks that turned to months, I couldn’t stop asking them.

I realize I’m not saying anything particularly novel here. I know suicides leave us all with questions and extended bouts of agonizing. But several years later, another suicide got me thinking in different directions.

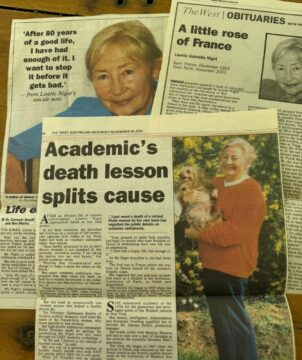

Though this one, they don’t easily call a suicide. This was a woman I knew not at all. Of French origin, Lisette Nigot had lived for years in Perth, Australia. She was in her late 70s, active and generally healthy. But she had started to wonder, as we all do, about the inevitable decline she faced as she grew steadily older.

In 1999, she attended a workshop conducted by Dr Philip Nitschke, an advocate of euthanasia known in some Australian circles as “Doctor Death”. Nitschke had already helped people with voluntary euthanasia, as Director of an organization called Exit International. After listening to Nitschke at the workshop, Nigot explained to him “that she planned to end her life sometime before she turned 80 … that she was not sick and that illness played no part in her decision.” (His own words).

Nitschke and Nigot met several times over the next few years. Initially, he seemed to have thought her resolve would crumble – she was in good health, was she not? – but Nigot remained firm. Eventually, he helped her with her decision, in the months leading up to September 2002. She had built up a stock of barbiturates that she had been taking for years. One day that September, she swallowed them and died.

That, of course, is the short version. There’s a documentary about Nigot, Mademoiselle and the Doctor that takes about an hour to tell her story.

Nigot’s death set off a vigorous debate among those who advocate for voluntary euthanasia. For even though she clearly wanted to end her life this way, even though she had thought about it long and hard and had settled on a reasonable way to do it, she was, in the end, in good health. Should she really have been given help and supported in this decision to take her life? Or should euthanasia be an option only for people with serious health concerns?

Questions worth asking. In fact, like with my college mate, I found myself grappling with these and many more questions that I could not easily answer. Some the same as with my college mate, some different.

I have a good idea what Nigot was thinking in her last few years. She seems to have been lucid, aware and rational about her situation in life and what lay ahead for her. Those who knew her never thought of her as depressed; on the contrary, the idea of choosing a voluntary death seems to have given her spirit and purpose. So I can imagine that her last months were consumed with putting in place a careful, diligent, complete closure to her life, knowing that’s what she wanted.

Shortly before she died, she wrote to a close friend (as it happens, also my close friend): “There, one sees the light at the end of the tunnel … You know that I’m neither depressed nor crazy … But really, I expect nothing more from life. Non, je ne regrette rien (“No, I regret nothing”) as [Edith] Piaf said. Do not be sad!”

And yet, and yet … what was she thinking as she took those barbiturates? Despite Piaf, despite her meticulous preparations, did she have any last-second doubts? Did she waver in her resolve?

Probably not, but there are more questions. The documentary tells us about a cancer patient who is terminally ill, but the law will not permit her to die voluntarily. Is choosing to die a matter to be decided, then, by the law? We create life and there’s no questioning legality there. Why is choosing how we die not legal too?

Or: is legality possible only for “older” adults in complete command of their mind, body and senses, meaning only they have the right to choose how, where and when they can die? If so, what does “older” mean, then – how old would this adult have to be? Is there an age below which they cannot be allowed this choice, and if so why?

Or: do you try to dissuade a person who has made a choice like this? Nigot decided she had lived long enough. How does anyone argue with that without dealing in cliches and platitudes? “Who was I to tell her otherwise?” Nitshcke asked, about her decision. “[S]he was an intriguing, enchanting woman and while it saddened me greatly when she decided to leave, her suicide was her decision and her right.”

I’m steeped right now in these memories, in all this agonizing, because someone else I know took his life just a few days ago. To us who knew him, he had everything going for him: a lovely family, a long and successful career, plenty of friends and admirers and a life of financial independence, indeed comfort. He had a booming laugh, a broad and infectious smile, a knack for telling the stories of innumerable intriguing things that had happened to him, a talent for listening, and a rounded, affable, always warm outlook on life.

Yet something in that picture had soured, so badly that he chose to end it all.

After losing him, his friends circulated a sheet of paper on which he had written, as a teenager, a long list of principles he expected to live by. Among them:

- To be always open to new possibilities that life may offer.

- To write and publish, with courage and fervor.

- To explore the unknown, and not be afraid of hard lessons.

To us who knew him, those words, and indeed all the others on that sheet, shaped the full, vibrant life he led, or we thought he led. Yet his sudden death leaves us bereft and filled with questions, just as with my college pal and with Lisette Nigot. And the questions ask themselves late at night, while nursing a coffee, while working on this article. All the time. And again, there are no answers.

What was he thinking, in those last few moments? He made his way, early that morning, from his home to the place where he died. What did he feel as he left home for the last time? What was that trip like for him? What in his life had become so unbearable that death made sense?

What hard lesson had finally proved too hard?