by Alizah Holstein

How are we to live, to work, when the house we live in is being dismantled? When, day by day, we learn that programs and initiatives, organizations and institutions that have defined and, in some cases, enriched our lives, or provided livelihoods to our communities, are being axed by the dozen? Can one, should one, sit at the desk and write while the beams of one’s home are crashing to the floor? Or more accurately: while the place is being plundered? There have been moments of late when I’ve feared that anything other than political power is frivolous, or worse, useless. In those moments, I myself feel frivolous and useless. And worse than that is the fear that art itself is useless. Not to mention the humanities, which right now in this country is everywhere holding its chin just above the water line to avoid death by drowning. It can take some time to remember that these things are worth our while, not because they’ll save us today, but because they’ll save us tomorrow.

How are we to live, to work, when the house we live in is being dismantled? When, day by day, we learn that programs and initiatives, organizations and institutions that have defined and, in some cases, enriched our lives, or provided livelihoods to our communities, are being axed by the dozen? Can one, should one, sit at the desk and write while the beams of one’s home are crashing to the floor? Or more accurately: while the place is being plundered? There have been moments of late when I’ve feared that anything other than political power is frivolous, or worse, useless. In those moments, I myself feel frivolous and useless. And worse than that is the fear that art itself is useless. Not to mention the humanities, which right now in this country is everywhere holding its chin just above the water line to avoid death by drowning. It can take some time to remember that these things are worth our while, not because they’ll save us today, but because they’ll save us tomorrow.

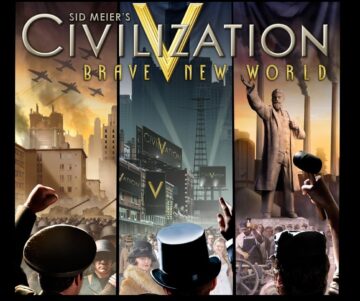

In my previous essay for 3 Quarks Daily, I wrote about how the acronym for the Department of Government Efficiency—DOGE—is possibly an allusion to the Venetian doge. For most of the Middle Ages, the doge was the city republic’s chief magistrate and its highest-ranking oligarch. The connection linking DOGE and doge, I suggested, was the video game Civilization V: Brave New World. In this game, players can choose to play the blind Doge Enrico Dandolo, who at ninety years old led the Venetian and crusader troops on the Fourth Crusade, ultimately diverting the crusade from its initial objective of Egypt and instead attacking two Christian cities, first Zadar on the Dalmatian coast, and then, more famously, Constantinople. Someone who has spoken publicly about playing this game is Elon Musk, and if I had to hazard a guess, I’d say he learned some of his history from it.

What does the Fourth Crusade look like in a video game? A Civilization V wiki supplies us with historical background and a summary sketch of Doge Enrico Dandolo: “He took control,” it explains, “of a mercantile power in decline, riven by corruption and inefficiency, challenged by great and small powers across the region. Trade had declined, and its military was moribund. By his death he had ended all outside threats to its influence, and made it the dominant power in Mediterranean trade again.” Corruption and inefficiency: those words ring a bell. Declining trade and complaints about a feeble military? Those too.

And yet there is much history that the wiki omits. Importantly, it neglects to mention that Doge Dandolo defied Pope Innocent III’s explicit prohibition against attacking allied lands. The pope excommunicated him for it, though in the two and a half years that Dandolo lived before dying on the crusade, the pope’s condemnation never appears to have made much of a difference. And another thing the wiki neglects to mention is the shocking violence of the plundering of Constantinople.

It was this week 821 years ago that Enrico Dandolo led the crusader forces in their siege, which began on April 9. Constantinople’s walls were breached on April 12, and the pillaging continued for three horrendous days. The early thirteenth-century Greek historian Niketas Choniates provided a detailed account of what it felt like to see the city rent asunder.

“The images, which ought to have been adored, were trodden under foot! Alas. The relics of the holy martyrs were thrown into unclean places!”…“They snatched the precious reliquaries, thrust into their bosoms the ornaments which these contained, and used the broken remnants for pans and drinking cups…”…“The sacred altar [of the church of Hagia Sofia], formed of all kinds of precious materials and admired by the whole world, was broken into bits and distributed among the soldiers, as was all the other sacred wealth of so great infinite splendor.

When the sacred vases and utensils of unsurpassable art and grace and rare material, and the fine silver, wrought with gold…and the door and many other ornaments, were to be borne away as booty, mules and saddled horses were led to the very sanctuary of the temple…”

“Nothing was more difficult and laborious than to soften by prayers, to render benevolent, these wrathful barbarians, vomiting forth bile at every unpleasing word, so that nothing failed to inflame their fury. Whoever attempted it was derided as insane and a man of intemperate language. Often they drew their daggers at anyone who opposed them at all or hindered their demands.

No one was without a share in the grief. In the alleys, in the streets, in the temples, complaints, weeping, lamentations, grief, the groaning of men, the shrieks of women, wounds, rape, captivity, the separation of those most closely united. Nobles wandered about ignominiously, those of venerable age in tears, the rich in poverty. Thus it was in the streets, on the corners, in the temple, in the dens, for no place remained unassailed or defended the suppliants. All places everywhere were filled full of all kinds of crime. Oh, immortal God, how great the afflictions of the men, how great the distress!”[1]

I wrote a book in which one theme was the consolation that history and literature can provide when we endure our own tough times. I know what it means to be saved from despair by a book, by a poem, by a story that speaks across time. The account of Constantinople’s destruction at the hands of Enrico Dandolo and his crusader troops is different, although no less valuable. It does not console so much as offer a glimpse of the consequences of human greed and political recklessness. I’ll leave it to you, reader, to decide whether the pillage and plundering we have seen these last two months is greater or lesser than those three days in Constantinople.

***

[1] S.J. Allen and Emilie Amt, eds. The Crusades: A Reader (Broadview Press: Ontario, 2003), 234-6.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.