by Richard Farr

I read somewhere that Mexico City has more museums and art galleries than any city in the world except London. Seems plausible: two weeks wasn’t enough, and would not have been enough even without all the hours spent wandering the boulevards, exploring labyrinthine food markets, and drinking tall glasses of maracuya juice chased by marginally smaller quantities of pulque and mescal. The problem is, you can only gulp down so many cool historically significant artifacts before you cease to be able to see clearly, a fact that a single institution was enough to illustrate.

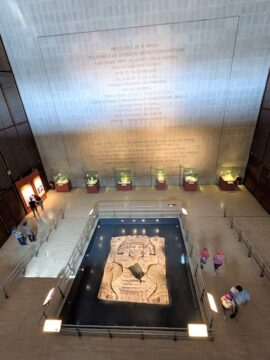

You get to the Museo Nacional de Antropología through Bosque de Chapultepec, nearly 2,000 acres of lakes and flowering trees that includes both the ruins of Moctezuma II’s private hot tub and so many lesser museums that they outnumber the squirrels. Built in 1964, the national cultural flagship is “only” a third the size of the Louvre but seems at least as big.

I’ve long assumed I’ll be on the shortlist if there’s ever a Nobel Prize for Loathing Brutalist Architecture, but I’m here to withdraw my nomination: Pedro Ramírez Vázquez’s design is clever, appropriate, imaginative, and (strange word amid all that concrete, but I’ll use it) lovely. And once you’ve absorbed the improbable grandeur of the monopole-canopied courtyard, everything inside seems monumental too, not just the twenty-ton carvings.

The rooms devoted to “Introduction to Anthropology” looked fascinating but not all that specific to the story of digging up Mexico. So we skipped through it, were also pretty cavalier about the acres of modern ethnography upstairs, and instead concentrated our minds on the Toltecs. The Oaxacans. The Maya. The Olmecs. The Zapotecs. The Mixtecs. The Aztec/Mexica…

It’s a brilliant assemblage beautifully displayed. Among many other thoughtful features, the main rooms open out into a series of gardens that are continuous with the indoor collection. But after four or five hours you reach historical-cultural overload – and the evidence for this is that you’re standing in front of something exquisite and realize guiltily that you’ve yet again confused Teotihuacán with Tenochtitlán. You’ve also started to hallucinate about the possibility of staring into space for half an hour over a plate of chilaquiles.

I kept coming back to that muddled sense of delight, fascination and defeat. On another day we went to the Zócalo, the giant square at the city’s center, over which the Catedral Metropolitana presides like an elderly abuela, lop-shouldered and arthritic-looking after too many encounters with earthquakes. Behind the cathedral lies the Templo Mayor, the true heart of Aztec Tenochtitlán, which lay all but buried until the 1970s. When Cortés showed up at the end of 1519 the principal building would have been nearly as tall as the cathedral is now; in 1520, in his temporary absence, the Habsburg Boys ambushed and murdered almost the entire Mexica nobility here, during a religious ceremony; in 1521, when Cortés returned, they levelled the city.

The great temple was reduced to sun-baked piles of stone. You glide over the stones on raised walkways now, trying to decipher signs that have themselves been half-erased by the sun, and frankly it’s a bit of a bore if you’re not a professional digger. But the attached museum, though more limited in scope and scale than its cousin in the park, is another prestige institution that makes you yearn for several extra days and a sleeping bag. The Aztecs were here for only a handful of generations, but they were culturally complicated and astonishingly productive.

Only one museum in Mexico, with comparable material, didn’t make me feel culturally exhausted or embarrassed by my ignorance in this way – and the Museo de Arte Prehispánico de México Rufino Tamayo, in Oaxaca, pulled off this trick by being (I suppose one can say) an art museum, but perhaps more properly and more simply an art gallery.

The eponymous artist, Rufino Tamayo – a contemporary and rather tart critic of the more famous Diego Rivera – learned his craft in the early 1920s when he worked in a museum of archaeology and found that he liked to draw the objects in the collection. Thirty years later he and his wife Olga started acquiring pre-hispanic artifacts from around the country; Tamayo gifted their collection to the city of his birth. But there was this stipulation: the objects were to be displayed as they had been collected – not as items of historical or archaeological significance but as individual works of art. So in the house on Avenida José María Morelos you are invited to see them in this spirit, and put their antiquity aside, and learn or re-learn what you so easily forget in those big museums: that these things can be celebrated for their grace and wit and excellence alone.

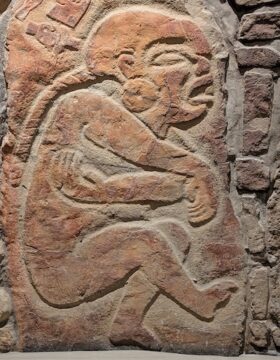

The human figures especially reward that appreciation, not least because of the gentler way that they remind you of the fact you’ve already been beaten over the head with: “pre-hispanic” is not the name of a single group, period, style or ethnicity but of scores of cultures and languages spread across millennia – a diversity in the light of which, say, “All Europe since the Renaissance” would seem a narrow specialization.

But these figures also underlined for me a problem with all art that’s far from us in time or culture: what exactly is it that we are supposed to be looking at? The faces are realistic, or they’re abstract. They seem to frown, or they seem to smile. Many, you want to call whimsical. But what these people (or the hands that made them) were thinking and feeling is lost to us, along with most of their languages. You think you recognize a facial expression across the centuries, but the harder you look the more the meaning shifts, retreats, deliquesces into enigma: another stone Mona Lisa.

Back to the capital-M Museums then, for their historical context. But can archaeology do enough for us? I’m always skeptical about signs that tell me an object “symbolised military strength” or “was probably used in religious ceremonies”; I want to grab the diggers by their dusty lapels and say “Come on! Be brave and admit it! You don’t really have a clue what this meant to them, do you?”

But sometimes a hard fact can be teased out that does correct earlier errors, and sometimes you wish the hard fact had been left well alone. Groups of figures known as danzantes (dancers) are here. I’d also seen some of them in situ at Monte Alban, the Zapotecs’ thousand-year redoubt (desde 500 años antes de Cristo hasta 500 años después, aproximadamente). Turns out the danzantes were more probably captured prisoners whose fun-loving postures are to be explained by the fact that they’d had their arms broken prior to castration and sacrifice.

Good old civilization – the lure of power and its attendant terrorism never ends.

On the other hand, the artist’s imperative to bear witness is also alive and well; one of our favorites among many pieces of gorgeous wall art in Mexico had been put up only days earlier:

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.