by Ed Simon

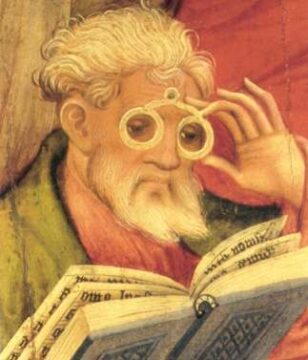

The twentieth-century Russian critic Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of the “chronotope” is among the more enigmatic concepts in literary theory, a discipline not defined by a deficit of them. In his 1937 essay “Forms of Time in and of the Chronotope in the Novel,” later published in his seminal collection The Dialogic Imagination, Bakhtin writes of his eponymous neologism that it involves the “intrinsic connectedness of temporal and spatial relationships that are artistically expressed in literature,” consciously drawing from Einstein’s discovery of space-time in a manner that’s metaphorical, but as the critic makes clear, “not entirely.”

What Bakhtin is getting at, in a manner that may seem esoteric but is estimably useful, is that in a given work of literature, space and time are not separatable, but inextricably connected, and that furthermore a particular relationship between those two qualities – that is a particular chronotope – is what defines specific literary genres. Within a given chronotope, “spatial and temporal indicators are fused into one carefully thought out, concrete whole,” writes Bakhtin, “Time… thickens, takes on flesh, becomes artistically visible; likewise, space becomes charged and responsive to the movements of time, plot and history.”

This year I tried to read as many examples of Bakhtin’s favored form of the novel as I could, and as always I didn’t go into my casual reading with a preordained theme in mind, but perhaps because of the exigencies of our current historical moment, many of the works on my list this year were obsessed with time, with thickness and fleshiness, and how that temporality connects to space. Novels took place in the past, present, and future, in alternate histories and as kaleidoscopic nesting narratives, but throughout those that impressed upon me the most urgency there was a distinct sense of the chronotope, of how fiction is a form of time travel.

The chronotope is not a dissimilar concept to the more popular “world building.” Though they’re not reducible to each other, nonetheless world building shares some of the same concern with thickening out the details of time and space. Furthermore, though world building is most often associated with detailed fantasy and science fiction, all genres grapple with the idea, at least a bit. Minimalist works answer the quandary of world building in a manner that’s different from a baroque doorstopper, but that a world has been built in either case is not to be doubted. Nor should it be taken that “realism,” ironically among the least realistic of genres, doesn’t build its own fictional worlds, though a winning tussle with verisimilitude would begin to resemble Borges’ map that’s equivalent to the territory.

A genre that’s consciously concerned with world building is that of alternate history, that subgenre of science fiction which imagines how history would have commenced had some hinge moment in the past occurred differently. Such works tend to focus on a Greatest Hits collection of limited examples – What if the Confederates won the Civil War? Hitler World War II? – that it can frequently seem to have been fully expended. That’s why two works that I read were so insightful, incisive, and most of all invigorating, by imagining alternate worlds so fully different from other novels in the genre. French novelist Laurent Binet in Civilizations and British novelist Francis Spufford in Cahokia Jazz both develop what could be called “counter-colonial alternative fiction,” that is envisioning what the world would have been like had the Columbian Exchange of half-a-millennium ago not commenced in the brutal manner that it had. In the process, both present cutting analyses of colonialism and history through the prism of fully realized and fascinating characters.

Binet, most known in the United States for his stunning HHhH which dramatized the assassination of the SS officer Reinhard Heydrich while simultaneously redefining the genre of the historical novel, imagines a complicated alternate history in Civilizations whereby the colonialism of the sixteenth-century happens in reverse. Here Montezuma conquers the Hapsburgs, and the Aztecs compete against the Incas as both establish toeholds in Spain, France, England, and the Holy Roman Empire. Historical personages from Montaigne to Cervantes make an appearance while Binet interrogates the philosophical differences between Western and indigenous cultures (though, of course, in Civilizations those terms are reversed). More a parable than a traditional novel (though Binet’s parallel world isn’t entirely unconvincing in the explanation of how it came about), Civilizations is fundamentally about differences in belief between the Indians and the Europeans, where the later maintain that “faith in the Sun is not taught. All one must do is look up.”

Spufford takes the history of indigenous America as his subject as well, constructing a believable alternate version of the ancient Midwestern metropolis of Cahokia which in his telling has survived until the 1920’s. In Cahokia Jazz, the historical city that had been abandoned by the plains Indians by the time of European conquest endures as a metropolis that’s part Chicago and part Tenochtitlan, a once independent multiethnic kingdom uneasily integrated into the United States where a seeming ritualistic murder threatens to make the city violently combust. As in Spufford’s brilliant Golden-Hill set in eighteenth-century New York, the author exhibits an incredible eye for world building detail. Cahokia becomes a fully realized setting, from its jazz joints to its ball fields, its ancient palaces to the modern police precinct, and as with Binet both authors grapple with difficult histories of race and colonialism through the subtle tool of genre fiction. At the metaphysical level, what’s investigated isn’t just history – but time. “The world turns, but it is not a clockwork mechanism,” writes Spufford, it is a “circular dance, from birth to death to resurrection, through arches of flowers, and arches of bread, and arches of skulls. We dance the turning world, and it dances us.”

History requires as much world building as does alternate history, as both HHhH and Golden-Hill demonstrate. This year I read a wealth of historical fiction, none of it featuring Regency aristocrats or among bodice-ripping pirates, but in nearer locales from 2004 Dallas to the Democratic primary campaign of four years later. Alexander Manshel in The Nation argued this year that a “quiet revolution has taken place in American fiction,” noting the preponderance of historical novels that have been critically lauded or nominated for major awards, concluding that “Contemporary fiction has never been less contemporary.” Two writers mentioned by Manshel – Viet Nguyen and Hernan Diaz – “are less interested in the way we live now than the way we were.” There’s some truth to Manshel’s argument, but the dichotomy between past and present is a bit more porous than that stark differentiation would have it, so that in many ways Nguyn and Diaz, as well as Vinson Cunningham, Aleksander Hemon, and Andrew O’Hagan, explain how we live now by recourse to the way we were.

Diaz’s Pulitzer Prize winning Trust is a case in point. Evocative of American heavyweights including Henry James, Edith Wharton, and F. Scott Fitzgerald, Trust is evidence for the contention that all Great American Novels are really about money. Ingeniously constructed, Trust’s narrative is composed as four nesting dolls of text. The first is a Gatsby-like 1920s novel entitled Bonds about the distant and conniving financier Benjamin Rask, the second My Life is a memoir of Andrew Bevel, the (in-the-novel) real industrialist and ostensible basis for Rask, the third is A Memoir, Revisited by Ida Partenza, the anarchic-minded ghost-writer for the second text, and the final section is Futures, the reminiscences of Andrew’s brilliant wife Mildred who has been consigned to a sanitarium. All of these characters (fictional or “fictional”) are molded by money – so that sometimes, for a bit, they get to do the molding back – but ultimately finance occupies a position that God once did. “We triumph, but it is not really we who fail,” writes Diaz, “we are ruined by forces beyond our control.”

Forces beyond our control are also the subject of Nguyen’s The Sympathizer, a book as worthy as any written in this century to be called a classic. Rather than finance (well rather than finance explicitly), Nguyen’s tale of a North Vietnamese spy stationed in the United States is concerned with questions of colonialism and resistance, global politics and American self-regard. Often drawing comparisons to Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man because of Nguyen’s similarly nameless narrator, the language in The Sympathizer is cutting and often hilarious, a post-Vietnam (or post-American?) novel about our dangerous myths of exceptionalism, where the “point was that it was the American story they watched and loved, up until the day that they themselves might be bombed by the planes they had seen in American movies.”

The spectacle of militarism is very much the central concern in Ben Fountain’s 2012 Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk. As Nguyen’s novel is to America’s malaise after the fall of Saigon, so is Fountain’s about the media-saturated, propaganda spectacle that was George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq. The titular army grunt of Fountain’s novel is a war hero involved in a vicious firefight in Iraq, invited along with his squadron to a Thanksgiving Dallas Cowboys game, with the action of Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk circumscribed by four quarters (and a Beyonce half-time performance). Billy Lynn is a character crafted with psychological incision, simultaneously a naïve hayseed and a cynical, battle-hardened warrior, but always a man who is fully aware of how he and his comrade’s experience is transformed into patriotic pablum for Americans distant from the stupid war that they cheer on. “Somewhere along the way America became a giant mall with a country attached,” wonders Fountain’s narrator, and it’s a truth even more disturbing for its accuracy.

The political legacy of the Iraq War, at least indirectly, is a concern in Vinson Cunningham’s audaciously titled Great Expectations. Cunningham, like Nguyen, shares far less with Charles Dickens than he does with Ellison, as Great Expectations explores political disillusionment for a nameless Black narrator in the same manner that The Invisible Man did. Rather than communism, however, the narrator of Great Expectations is enthralled to the centrist liberal politics of hope and change as he’s recruited into the Democratic primary campaign of an also unnamed junior Senator from Illinois who could become the first Black president of the United States (whom the politician is isn’t exactly subtle). Cunningham carefully explicates the slow accumulation of political disappointment that inevitably occurs within any movement, yet Great Expectations is never cynical, that even amid a campaign we all “wanted to be real in a way that history wasn’t.”

When it comes to historical fiction, I’ve always had an attraction to an eastern European setting, where the never-ending tussle of forces in the form of grand empires forever in competition highlights just how small and contingent the individual can be. Prague, by the American novelist Arthur Phillips, is set not in the Czech metropolis, but rather in post-communist Budapest, where all the characters pine for the titular city as a hipper and more promising place to make a name for oneself. These characters are an “unlikely group pieced together… from parties and family references, friend-of-friend happenstance, and… sheer, scarcely tolerable intrusiveness – five people who, in normal life back home, would have been satisfied never to have known one another.” Phillips focuses on a very particular period, in between the hope at the Cold War’s end, but before the inevitable rise of Putinest authoritarianism (with traces of Orban’s coming obvious throughout). In some ways, Prague is a contemporary la belle epoque novel that captures American naivety (and most of the characters are Americans) about the “end of history” and the supposed providential arrival of free markets. His Budapest is dingy but elegant, ancient but transforming, haunted but hungry. A novel of the Hungarian palimpsest, buffeted between the Ottomans and the Hapsburgs, the German fascists and the Soviet communists. Prague is an old-fashioned novel of ideas, a narrative written in prose both lush and introspective that evokes those mid-century paperbacks which promised to capture the zeitgeist.

Katya Apekina’s Mother Doll is as polyphonic as Phillips’ account of Budapest friends and frenemies, a crucial difference being that the novel’s voices are often within her main character Zhenia’s fevered brain. Like her author, Zhenia is a Russian-born immigrant to the United States, but presumably unlike Apekina, the main character of Mother Doll can act as a medium for an assortment of long-dead women and men who exist in a shoal-like shadow realm between life and death. As heavy as this sounds, Apekina writes about history, family, and trauma with an admirably Slavic sense of humor, imbuing this narrative with a Nabokovian wit. Zhenia, a failed actress from New York in that most American of sunny metropolises Los Angeles, is contacted by her great-grandmother, whose tale of life in Bolshevik Moscow alternates with the present day. Here, that most Russian of literary concepts the chronotope, is a complicated nesting doll, past and present forever turning back on each other, where the center piece’s identity is obscured. In Apekina’s understanding, there is something personal in metaphysics, where we’re bedeviled “To have nobody. For eternity to be in a crowd but to always be lonely.”

Bosnian-American writer Aleksander Hemon took up similar themes in his incandescently gorgeous The World and All that it Holds, an epic about the uncomplicatedly beautiful queer love between two Austro-Hungarian soldiers on the Great War’s eastern front, Sephardic Pinto and Islamic Osman. Hemon, a modern-day Joseph Conrad and among the greatest English prose stylists writing today, recounts the two (and then the one’s) journey eastward, from capture by the Russians, imprisonment in central Asia, and eventual arrival in Shanghai during the Japanese invasion. Throughout, Hemon forges a language composed of English, Bosnian, Ladino, several central Asian languages, and Chinese, a tongue that’s only literally understandable by the characters and yet nonetheless decipherable by any one immersing themselves in this humane and aching novel. “If you live long enough,” writes Hemon, “you learn that nothing has ever been, nor will it ever be, the way it used to be.”

That’s a lesson learned in a startling manner by Captain Graham Gore in Kaliane Bradley’s delightful The Ministry of Time. Bradley’s novel concerns a secret agency deep within the bowls of the British intelligence apparatus, a group that is dedicated to time travel and the acclimation of people filched from various moments in history in which they otherwise would have perished. An English Civil War veteran and an unlucky officer from the western front, a peasant woman rescued from the plague of 1665 and Gore, who otherwise would have frozen to death in an Arctic expedition during the Victorian Era. With pluck and good humor, Bradley’s novel explores the exigencies of history, and the way in which all of us are, to varying degrees, in exile from the past. The Ministry of Time is written with an adept ear towards dialogue, the romance between Gore and his contemporary handler, an unnamed daughter of a British father and Cambodian refugee mother, being accomplished with charming flair. Gore is completely believable as a character, Bradley’s accomplishment being that rare alchemy that makes an otherwise (mostly) fictional character appear as flesh, a man who for the narrator could hold “me in his arms, the way that poems hold clauses.”

A similar engaging character was the perfectly named Cyrus Shams in poet Kavah Akbar’s first novel Martyr! A bisexual recovering alcoholic poet from Indiana, Cyrus is obsessed with writing a cycle about martyrdom, haunted as he is by his Iranian mother’s death after her commercial airliner was accidentally shot down decades ago by the United States Navy. Shifting between reality and dream, Martyr! is about many things – recovery, ethnicity, family, trauma, poetry – but Akbar’s concern is nothing less than the collaborative project of reality itself, whereby “Love was a room that appeared when you stepped into it.”

Among my two favorite books this year were a New England diptych – Ben Shattuck’s series of interconnected short stories The Invention of Sound and David Mason’s magisterial North Woods. Both works can register a multiplicity of voices, both are narratively complex, both are written with epic historical sweep and granular local attention, both have their moments of dark Yankee humor, and both interrogate what it means to be an American through the prism of New England itself. Shattuck’s collection, which is perhaps more apt to be called a shaggy-dog novel, follows several different characters from the seventeenth-century onward, the collection itself asynchronously assembled, but where “history is personal, even when it isn’t.” An early twentieth-century ethnographer collecting folk songs with his male lover, a doomed logging expedition in New Hampshire, a painter who discovers a whale-bone dildo from the nineteenth-century bricked up in his beach home. The Invention of Sound is a work familiar with both the salt and mountain air, a work fit for a Cape Cod summer and a New Hampshire autumn.

Mason’s North Woods was the most magisterial novel I read this year, a work that in its scope and attention demonstrates how a single, small place can be fully realized world. Ostensibly the tale of a single western Massachusetts home throughout its four-century history in the woods, from Puritan lovers’ hideaway to Gilded Age hunting lodge, abolitionist hiding-spot to contemporary hotel, North Woods is nothing less than a history of America from the vantage point of this singular wooded spot. Mason’s genius for voice is astounding; throughout North Woods he imitates any number of registers, including Indian captivity narratives, gothic romances, ballads, nineteenth-century epistolary novels, true crime, and science fiction. Not only that, but it’s also a work that despite its subject is often funny (and there are ghosts as well). From the colonial frontier to the Anthropocene, North Woods charts how the “only way to understand the world as something other than a tale of loss is to see it as a tale of change,” a work which proves that the novel remains the most potent form yet developed for capturing how time thickens and space changes.

***

Other Fantastic Books I Read in 2024

The Heart in Winter by Kevin Barry

The Audacity by Ryan Chapman

The Book of Ayn by Lexi Freiman

The Book of George by Kate Greatwell

The Hypocrite by Jo Hamya

The Dog Stars by Peter Heinert

Wellness by Nathan Hill

Pym by Mat Johnson

Reunion by Elise Juska

Memory Piece by Lisa Ko

Creation Lake by Rachel Kushner

Old King by Maksim Lakutsoff

American Mermaid by Jessica Langbein

The Nude by C. Michelle Lindley

The Future was Color by Patrick Nathan

Caledonian Road by Andrew O’Hagan

Godwin by Joseph O’Neil

Hum by Helen Phillips

The Late Americans by Brandon Taylor

Reboot by Justin Taylor

Margo Has Money Problems by Rufi Thorpe

Horror Movie by Peter Tremblay

Horse by Willie Vautin

Catalina by Karla Cornejo Villavicencio

The Winner by Teddy Wayne

***

Ed Simon is the editor of Belt Magazine, an emeritus staff-writer for The Millions, a columnist at 3 Quarks Daily, and Public Humanities Special Faculty in the English Department of Carnegie Mellon University. The author of over a dozen books, his upcoming title Relic will be released by Bloomsbury Academic in January as part of their Object Lessons series, while Devil’s Contract: The History of the Faustian Bargain will be released by Melville House in July of 2024.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.