Ruth Marcus in The Washington Post:

The upside-down U.S. flag flying at the home of Supreme Court Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. — only days after the Trump-inspired insurrection on Jan. 6, 2021 — shouldn’t come as much of a surprise. After all, Alito has been doing the moral equivalent for years —and at the office, which is way worse. In oral arguments, in speeches and in opinions themselves, he is the Fox News-iest of justices, most likely to pick up on conservative media talking points and most predictably partisan when it comes to his votes.

The upside-down U.S. flag flying at the home of Supreme Court Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. — only days after the Trump-inspired insurrection on Jan. 6, 2021 — shouldn’t come as much of a surprise. After all, Alito has been doing the moral equivalent for years —and at the office, which is way worse. In oral arguments, in speeches and in opinions themselves, he is the Fox News-iest of justices, most likely to pick up on conservative media talking points and most predictably partisan when it comes to his votes.

Of course, the flag flying was grossly improper, an apparent endorsement of the “Stop the Steal” movement. Alito himself seemed to recognize this as he blamed his wife for the oh-say-can-you-see moment, asserting it flew just briefly after a neighborhood dispute escalated into a profane personal attack on Martha-Ann Alito. She should apologize; whatever the provocation, justices and their wives should behave in a way that is above reproach. This wasn’t. And the justice himself should provide more information about how long the flag was up, how quickly he intervened, and why. That would help the public assess whether Alito should heed calls from Democrats such as Sen. Dick Durbin (Ill.) and House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries (N.Y.) to recuse himself from the election-related cases now pending, one involving former president Donald Trump’s assertion that he has absolute presidential immunity from criminal prosecution for his official acts, the other concerning the scope of an obstruction statute under which Trump has been charged.

I’m not there — not yet, although The Post’s reporting on neighbors who said the flag was upside down for two to five days gives me pause.

More here.

Getting microbes to eat plastic is a frequently touted solution to our growing waste problem, but making the approach practical is tricky. A new technique that impregnates plastic with the spores of plastic-eating bacteria could make the idea a reality. The impact of plastic waste on the environment and our health has gained increasing attention in recent years. The latest round of UN talks aiming for a global treaty to end plastic pollution

Getting microbes to eat plastic is a frequently touted solution to our growing waste problem, but making the approach practical is tricky. A new technique that impregnates plastic with the spores of plastic-eating bacteria could make the idea a reality. The impact of plastic waste on the environment and our health has gained increasing attention in recent years. The latest round of UN talks aiming for a global treaty to end plastic pollution  Whether mobilizing for war or (re)constructing advanced manufacturing capabilities in peacetime, success turns on the functioning of complex supply chains. But this truth was long forgotten – or at least under-appreciated. Not until recent supply-chain shocks did academics, policymakers, and others start paying more attention to the complicated, barely studied “meso” (middle) domain between microeconomics and macroeconomics.

Whether mobilizing for war or (re)constructing advanced manufacturing capabilities in peacetime, success turns on the functioning of complex supply chains. But this truth was long forgotten – or at least under-appreciated. Not until recent supply-chain shocks did academics, policymakers, and others start paying more attention to the complicated, barely studied “meso” (middle) domain between microeconomics and macroeconomics. For thousands of years, humankind has fancied itself the apex of creation and the dominant force in the world. Yet humans are now gripped by the fear that yet another species of our own creation—artificially intelligent machines—will presently displace us from our position of unchallenged domination, perhaps even enslaving us.

For thousands of years, humankind has fancied itself the apex of creation and the dominant force in the world. Yet humans are now gripped by the fear that yet another species of our own creation—artificially intelligent machines—will presently displace us from our position of unchallenged domination, perhaps even enslaving us. I spent

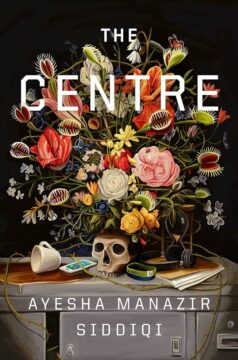

I spent  Language as self, language learning as magic, the mortifications of the flesh: these themes run through The Centre, a debut novel by British-Pakistani writer and translator Ayesha Manazir Siddiqi. Its narrator, Anisa, is a Pakistani translator of Urdu living in London, grappling with tensions of her immigrant identity and cosmopolitan desires. Yes, she had achieved her dream of moving to England but dislikes the cold and the myriad forms of casual racism she encounters. She complains that living outside of Pakistan has tainted her Urdu (her mother tongue) with Hindi words, and she resents the fact that she uses Urdu merely to translate Bollywood film subtitles — as opposed to the great literature she admires. To top it off, her other language, French, is mediocre. « Not like French-person French, » she complains to a friend.

Language as self, language learning as magic, the mortifications of the flesh: these themes run through The Centre, a debut novel by British-Pakistani writer and translator Ayesha Manazir Siddiqi. Its narrator, Anisa, is a Pakistani translator of Urdu living in London, grappling with tensions of her immigrant identity and cosmopolitan desires. Yes, she had achieved her dream of moving to England but dislikes the cold and the myriad forms of casual racism she encounters. She complains that living outside of Pakistan has tainted her Urdu (her mother tongue) with Hindi words, and she resents the fact that she uses Urdu merely to translate Bollywood film subtitles — as opposed to the great literature she admires. To top it off, her other language, French, is mediocre. « Not like French-person French, » she complains to a friend. It is one of the recurring plotlines in the psychodrama of U.S. politics: A talented and charismatic young reformer goes to Washington, is hailed for taking on a corrupt and self-satisfied establishment, but in the end is nearly undone by inexperience, naiveté and unbending idealism. The latest “Mr. Smith” to hit the capital is Lina Khan, the crusading chair of the Federal Trade Commission who, at the age of 35, has become the wonky cult hero and legal wunderkind of a new progressive movement determined to break the economic and political power of Big Business and Big Tech.

It is one of the recurring plotlines in the psychodrama of U.S. politics: A talented and charismatic young reformer goes to Washington, is hailed for taking on a corrupt and self-satisfied establishment, but in the end is nearly undone by inexperience, naiveté and unbending idealism. The latest “Mr. Smith” to hit the capital is Lina Khan, the crusading chair of the Federal Trade Commission who, at the age of 35, has become the wonky cult hero and legal wunderkind of a new progressive movement determined to break the economic and political power of Big Business and Big Tech. It’s been 14 years since Goldman Sachs was vilified as a “vampire squid” by Matt Taibbi in Rolling Stone. “Organized greed always defeats disorganized democracy,” he concluded then. Goldman has since experienced some hard times, tarred by scandal (the

It’s been 14 years since Goldman Sachs was vilified as a “vampire squid” by Matt Taibbi in Rolling Stone. “Organized greed always defeats disorganized democracy,” he concluded then. Goldman has since experienced some hard times, tarred by scandal (the  As I’ve been researching and writing Boundless 2.0, I’ve found myself reevaluating many of the health and fitness strategies that I previously endorsed.

As I’ve been researching and writing Boundless 2.0, I’ve found myself reevaluating many of the health and fitness strategies that I previously endorsed. Imagine you had a friend who gave different answers to the same question, depending on how you asked it. “What’s the capital of Peru?” would get one answer, and “Is Lima the capital of Peru?” would get another. You’d probably be a little worried about your friend’s mental faculties, and you’d almost certainly find it hard to trust any answer they gave.

Imagine you had a friend who gave different answers to the same question, depending on how you asked it. “What’s the capital of Peru?” would get one answer, and “Is Lima the capital of Peru?” would get another. You’d probably be a little worried about your friend’s mental faculties, and you’d almost certainly find it hard to trust any answer they gave. Few writers have possessed the short-story format as thoroughly as the Canadian author and Nobel laureate

Few writers have possessed the short-story format as thoroughly as the Canadian author and Nobel laureate