McKenzie Prillaman in Nature:

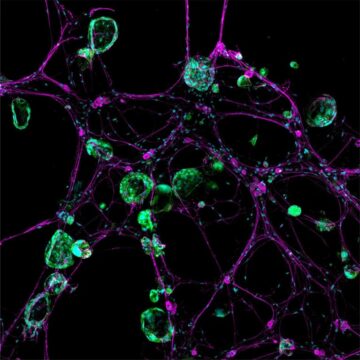

Lightning bolts of lime green flashed chaotically across the computer screen, a sight that stunned cancer neuroscientist Humsa Venkatesh. It was late 2017, and she was watching a storm of electrical activity in cells from a human brain tumour called a glioma. Venkatesh was expecting a little background chatter between the cancerous brain cells, just as there is between healthy ones. But the conversations were continuous, and rapid-fire. “I could see these tumour cells just lighting up,” says Venkatesh, who was then a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University School of Medicine in Stanford, California. “They were so clearly electrically active.”

Lightning bolts of lime green flashed chaotically across the computer screen, a sight that stunned cancer neuroscientist Humsa Venkatesh. It was late 2017, and she was watching a storm of electrical activity in cells from a human brain tumour called a glioma. Venkatesh was expecting a little background chatter between the cancerous brain cells, just as there is between healthy ones. But the conversations were continuous, and rapid-fire. “I could see these tumour cells just lighting up,” says Venkatesh, who was then a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University School of Medicine in Stanford, California. “They were so clearly electrically active.”

She immediately began to think about the implications. Scientists just hadn’t considered that cancer cells — even those in the brain — could communicate with each other to this extent. Perhaps the tumour’s constant electrical communication was helping it to survive, or even to grow. “This is cancer that we’re working on — not neurons, not any other cell type.” To see the cells fizz with so much activity was “truly mind blowing,” says Venkatesh, who is now at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts. Venkatesh’s work formed part of a 2019 paper in Nature1, which was published alongside another article2 that came to the same conclusion: gliomas are electrically active. The tumours can even wire themselves into neural circuits and receive stimulation directly from neurons, which helps them to grow.

More here.