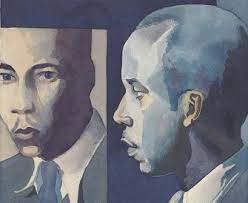

Melvin Rogers in Lapham’s Quarterly:

Debates about the representation of African Americans circulated throughout the 1920s—what kinds of depictions should be encouraged, who should be responsible for them, and what role black artists had in responding to negative descriptions and uplifting the race. These themes served as the subject of W.E.B. Du Bois’ 1926 symposium, “The Negro in Art: How Shall He Be Portrayed?” hosted in the NAACP’s magazine, The Crisis. Even a cursory glance at the responses to Du Bois’ question reveals that few believed African Americans were duty bound to direct their art to the cause of social justice. The unencumbered freedom of the artist, many argued, was far too important. As playwright and novelist Heyward DuBose argues, who himself was not an African American, black people must be “treated artistically. It destroys itself as soon as it is made a vehicle for propaganda. If it carries a moral or a lesson, they should be subordinated to the artistic aim.”

Debates about the representation of African Americans circulated throughout the 1920s—what kinds of depictions should be encouraged, who should be responsible for them, and what role black artists had in responding to negative descriptions and uplifting the race. These themes served as the subject of W.E.B. Du Bois’ 1926 symposium, “The Negro in Art: How Shall He Be Portrayed?” hosted in the NAACP’s magazine, The Crisis. Even a cursory glance at the responses to Du Bois’ question reveals that few believed African Americans were duty bound to direct their art to the cause of social justice. The unencumbered freedom of the artist, many argued, was far too important. As playwright and novelist Heyward DuBose argues, who himself was not an African American, black people must be “treated artistically. It destroys itself as soon as it is made a vehicle for propaganda. If it carries a moral or a lesson, they should be subordinated to the artistic aim.”

Du Bois’ essay “Criteria of Negro Art” is his answer to the symposium that he organized. But whereas most read this essay as the dividing line (and there is some truth in this) between Du Bois and many in the Harlem Renaissance, especially the writer and philosopher Alain Locke, the essay suggests closer proximity between these two figures. They each were seeking to avoid black artists needing to manage the unacceptable demands of what Langston Hughes called the “undertow of sharp criticism and misunderstanding” from black people and “unintentional bribes from whites.”

More here.