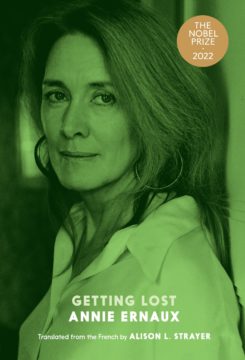

Maria Tumarkin in the Sydney Review of Books:

What a time to be reading about Annie Ernaux’s self-obliterating affair with S from the Soviet embassy in Paris, not that you’d sense that something’s in the air from the English-language reception to Getting Lost, Ernaux’s diary of the relationship, published in English last September. In the diary and in its generally admiring reviews S is described as a diplomat, apparatchik, attaché, ‘faithful servant of the USSR’ (Ernaux) and Brezhnev nostalgic/Stalin apologist when drunk. Also: ‘He is somewhat, not to say very, anti-Semitic: “Isn’t Mitterrand Jewish?” ’ Pretty standard stuff. Come on. He would have been KGB. And it matters not because he may or mayn’t have tried recruiting Ernaux – S kept their affair secret and appeared uninterested in converting her into an asset or using her connections (his anti-intellectualism was a turn-on for Ernaux). It’s possible in fact Ernaux was so erotically dazzling she shortcircuited, without realising, some good old planned sexual espionage (if so I’d like to read about it). She though wasn’t remotely intrigued by what S did when not with her: ‘I never knew anything about his activities, which, officially, were related to culture. Today, I am amazed that I did not ask more questions.’ Culture my arse. The KGB thing matters because an account of a prominent French writer, one of the greats to many, the most recent Nobel Prize winner losing her mind over a KGB stooge in the dying days of the Soviet Union reads, lands, sits, sticks, whatever the verb, differently after 24 February 2022.

What a time to be reading about Annie Ernaux’s self-obliterating affair with S from the Soviet embassy in Paris, not that you’d sense that something’s in the air from the English-language reception to Getting Lost, Ernaux’s diary of the relationship, published in English last September. In the diary and in its generally admiring reviews S is described as a diplomat, apparatchik, attaché, ‘faithful servant of the USSR’ (Ernaux) and Brezhnev nostalgic/Stalin apologist when drunk. Also: ‘He is somewhat, not to say very, anti-Semitic: “Isn’t Mitterrand Jewish?” ’ Pretty standard stuff. Come on. He would have been KGB. And it matters not because he may or mayn’t have tried recruiting Ernaux – S kept their affair secret and appeared uninterested in converting her into an asset or using her connections (his anti-intellectualism was a turn-on for Ernaux). It’s possible in fact Ernaux was so erotically dazzling she shortcircuited, without realising, some good old planned sexual espionage (if so I’d like to read about it). She though wasn’t remotely intrigued by what S did when not with her: ‘I never knew anything about his activities, which, officially, were related to culture. Today, I am amazed that I did not ask more questions.’ Culture my arse. The KGB thing matters because an account of a prominent French writer, one of the greats to many, the most recent Nobel Prize winner losing her mind over a KGB stooge in the dying days of the Soviet Union reads, lands, sits, sticks, whatever the verb, differently after 24 February 2022.

More here.

Life expectancy fell in the United States in 2021 for the

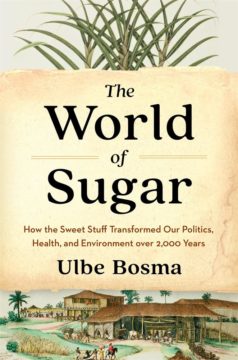

Life expectancy fell in the United States in 2021 for the  WHAT MIGHT DONALD RUMSFELD have in common with Frederick Barbarossa, Mormons, and Queen Elizabeth I’s rotting teeth? The answer is simpler than you might expect: the power and influence of sugar, a crystalline specimen of world-historical significance dissolved in your morning coffee or tea. A warmongering neocon, a Holy Roman emperor, pious Utahns, and a heavily cavitied pair of Tudor gnashers are part of an expansive cast of characters in Ulbe Bosma’s new work on the sweet stuff, The World of Sugar: How the Sweet Stuff Transformed Our Politics, Health, and Environment over 2,000 Years. This book is a tour de force of global history, one that helps us better understand the genesis of both modern capitalism and globalization.

WHAT MIGHT DONALD RUMSFELD have in common with Frederick Barbarossa, Mormons, and Queen Elizabeth I’s rotting teeth? The answer is simpler than you might expect: the power and influence of sugar, a crystalline specimen of world-historical significance dissolved in your morning coffee or tea. A warmongering neocon, a Holy Roman emperor, pious Utahns, and a heavily cavitied pair of Tudor gnashers are part of an expansive cast of characters in Ulbe Bosma’s new work on the sweet stuff, The World of Sugar: How the Sweet Stuff Transformed Our Politics, Health, and Environment over 2,000 Years. This book is a tour de force of global history, one that helps us better understand the genesis of both modern capitalism and globalization. We demand a lot from scientists. They are required to be objective, rigorous, and accurate, and to conduct their work free from the constraints of religion or politics. Few other areas of human endeavour are expected to be or valued as being so free from human error. At the same time, scientists are tasked with assessing and considering the potential consequences and applications of their work, and to act responsibly to maintain public trust in their whole system of knowledge. That is a burden that scientists must feel acutely today, as they come under attack from the instruments of misinformation.

We demand a lot from scientists. They are required to be objective, rigorous, and accurate, and to conduct their work free from the constraints of religion or politics. Few other areas of human endeavour are expected to be or valued as being so free from human error. At the same time, scientists are tasked with assessing and considering the potential consequences and applications of their work, and to act responsibly to maintain public trust in their whole system of knowledge. That is a burden that scientists must feel acutely today, as they come under attack from the instruments of misinformation. Kingsley Amis, the former Angry Young Man, lives in a large, early-nineteenth-century house beside a wooded common. To reach it, one makes a journey similar to that described by the narrator of Girl, 20 when he visits Sir Roy Vandervane: first by tube to the end of the Northern Line at Barnet; then, following a phone call from the station to say where one is, on foot up a stiff slope; and finally down a suburban road. But instead of being picked up en route by Sir Roy’s black chum, Gilbert, I was intercepted by Amis’s tall and imposing blond wife, the novelist Elizabeth Jane Howard.

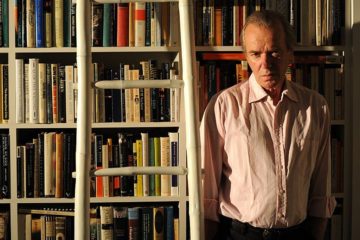

Kingsley Amis, the former Angry Young Man, lives in a large, early-nineteenth-century house beside a wooded common. To reach it, one makes a journey similar to that described by the narrator of Girl, 20 when he visits Sir Roy Vandervane: first by tube to the end of the Northern Line at Barnet; then, following a phone call from the station to say where one is, on foot up a stiff slope; and finally down a suburban road. But instead of being picked up en route by Sir Roy’s black chum, Gilbert, I was intercepted by Amis’s tall and imposing blond wife, the novelist Elizabeth Jane Howard. Martin Amis, whose caustic, erudite and bleakly comic novels redefined British fiction in the 1980s and ’90s with their sharp appraisal of tabloid culture and consumer excess, and whose private life made him tabloid fodder himself, died on Friday at his home in Lake Worth, Fla. He was 73.

Martin Amis, whose caustic, erudite and bleakly comic novels redefined British fiction in the 1980s and ’90s with their sharp appraisal of tabloid culture and consumer excess, and whose private life made him tabloid fodder himself, died on Friday at his home in Lake Worth, Fla. He was 73. Nadia Saah in Jewish Currents:

Nadia Saah in Jewish Currents: An interview with Adrienne Buller over at The Syllabus:

An interview with Adrienne Buller over at The Syllabus: Robert N. Watson in LA Review of Books:

Robert N. Watson in LA Review of Books: C

C THE DAY AFTER

THE DAY AFTER Reading Schulz’s works, it’s easy to see why he might have had such an effect on this array of creative minds. His stories defy description, explication, paraphrase. They are set in a phantasmagoric version of the city of Drohobycz (now in western Ukraine), where Schulz was born and died, and largely in and around the cloth shop on the market square that his parents owned, but in a version of these places where time and space have become molten and malleable. They take place in “years which – like a sixth, smallest toe – grow a 13th freak month” in “an illegal time… liable to all kinds of excesses and crazes”. The narrator’s father – a looming, manic, tragicomic version of Schulz’s own – at one point wastes away to nothing, leaving only “the small shroud of his body” and “a handful of nonsensical oddities”; at another he morphs into “a monstrous, hairy, steel blue horsefly”, a development that the narrator takes in his stride as just one of many “summer aberrations”. The stories read like the quintessence of the human imagination in its densest, strangest form, as if his language were a thick, sweet concentrate of the creativity that other writers dilute to a sippable weakness.

Reading Schulz’s works, it’s easy to see why he might have had such an effect on this array of creative minds. His stories defy description, explication, paraphrase. They are set in a phantasmagoric version of the city of Drohobycz (now in western Ukraine), where Schulz was born and died, and largely in and around the cloth shop on the market square that his parents owned, but in a version of these places where time and space have become molten and malleable. They take place in “years which – like a sixth, smallest toe – grow a 13th freak month” in “an illegal time… liable to all kinds of excesses and crazes”. The narrator’s father – a looming, manic, tragicomic version of Schulz’s own – at one point wastes away to nothing, leaving only “the small shroud of his body” and “a handful of nonsensical oddities”; at another he morphs into “a monstrous, hairy, steel blue horsefly”, a development that the narrator takes in his stride as just one of many “summer aberrations”. The stories read like the quintessence of the human imagination in its densest, strangest form, as if his language were a thick, sweet concentrate of the creativity that other writers dilute to a sippable weakness. It’s rare to come across a new Vietnam War memoir from a major publisher in 2023. Most were written decades ago, when memories were fresh and wounds still raw. That generation of soldiers has begun to pass away.

It’s rare to come across a new Vietnam War memoir from a major publisher in 2023. Most were written decades ago, when memories were fresh and wounds still raw. That generation of soldiers has begun to pass away. The most dangerous political experiment in Latin America is underway in El Salvador. A strange breed of populism is tipping the scale in the region’s age-old tug of war between authoritarianism and democracy. Rather than dividing the country, like populism usually does, it’s uniting it solidly behind a new consensus. More than anything, though, it’s succeeding, and doing so in the kind of impossible-to-miss way that turns heads up and down the hemisphere.

The most dangerous political experiment in Latin America is underway in El Salvador. A strange breed of populism is tipping the scale in the region’s age-old tug of war between authoritarianism and democracy. Rather than dividing the country, like populism usually does, it’s uniting it solidly behind a new consensus. More than anything, though, it’s succeeding, and doing so in the kind of impossible-to-miss way that turns heads up and down the hemisphere.