Richard V Reeves in Persuasion:

One hundred and fifty years ago this month, John Stuart Mill died in his home in Avignon. His last words were to his step-daughter, Helen Taylor: “You know that I have done my work.”

One hundred and fifty years ago this month, John Stuart Mill died in his home in Avignon. His last words were to his step-daughter, Helen Taylor: “You know that I have done my work.”

He certainly had. During his 66 years of life, Mill became the preeminent public intellectual of the century, producing definitive works of logic and political economy, founding and editing journals, serving in Parliament, and churning out book reviews, journalism and essays, most famously his 1859 masterpiece, On Liberty. Oh, and he had a day job, too: as one of the most senior bureaucrats in the East India Company.

What is too often forgotten about Mill is that he was as much an activist as an academic. Benjamin Franklin exhorted his followers to “either write something worth reading or do something worth writing.” Mill, like Franklin himself, is among the very few who managed to do both.

For Mill, liberalism did not only have to be argued for, it had to be fought for, too. He campaigned for women’s rights and was the first MP to introduce a bill for women’s suffrage into Parliament. He was a fiercely committed anti-racist, strongly supporting the abolitionist movement in the United States, and the North in the Civil War. Mill also led a successful campaign for the right to protest and speak in London’s public parks. In Hyde Park, the famous Speaker’s Corner stands today as a tribute to his victory.

More here.

The Japanese-born British novelist Kazuo Ishiguro is one of the most critically acclaimed authors writing in English today: the now 68-year-old was twice selected in the Granta Best of Young British Novelists issue, in 1983 and 1993, before going on to bag the Booker prize, the Nobel prize in literature and a knighthood. Earlier this year, he picked up Bafta and Oscar nominations too, for his adapted screenplay of Living, starring Bill Nighy. David Sexton suggests some good places to start for those who haven’t yet dipped in to his work.

The Japanese-born British novelist Kazuo Ishiguro is one of the most critically acclaimed authors writing in English today: the now 68-year-old was twice selected in the Granta Best of Young British Novelists issue, in 1983 and 1993, before going on to bag the Booker prize, the Nobel prize in literature and a knighthood. Earlier this year, he picked up Bafta and Oscar nominations too, for his adapted screenplay of Living, starring Bill Nighy. David Sexton suggests some good places to start for those who haven’t yet dipped in to his work.

One hundred and fifty years ago this month, John Stuart Mill died in his home in Avignon. His last words were to his step-daughter, Helen Taylor: “You know that I have done my work.”

One hundred and fifty years ago this month, John Stuart Mill died in his home in Avignon. His last words were to his step-daughter, Helen Taylor: “You know that I have done my work.” Perhaps the most fascinating thing here is the insistence that singing the song isn’t enough to help the supplicant who is in a crisis situation. It’s also essential to understand what the lyrics really mean. The Derveni author gets most irate when describing those who turn to other musical ritualists for enlightenment, for “they go away after having performed [the rites] before they have attained knowledge, without even asking further questions.”

Perhaps the most fascinating thing here is the insistence that singing the song isn’t enough to help the supplicant who is in a crisis situation. It’s also essential to understand what the lyrics really mean. The Derveni author gets most irate when describing those who turn to other musical ritualists for enlightenment, for “they go away after having performed [the rites] before they have attained knowledge, without even asking further questions.”

Imagine you’re in a room with a hundred American young adults, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed. Over their lifetimes, about 25 of them will have a

Imagine you’re in a room with a hundred American young adults, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed. Over their lifetimes, about 25 of them will have a  Half a decade ago, chemist Mark Levin was a postdoc looking for a visionary project that could change his field. He found inspiration in a set of published wish lists from pharmaceutical-industry scientists who were looking for ways to transform medicinal chemistry

Half a decade ago, chemist Mark Levin was a postdoc looking for a visionary project that could change his field. He found inspiration in a set of published wish lists from pharmaceutical-industry scientists who were looking for ways to transform medicinal chemistry Pictures from Brueghel and Other Poems

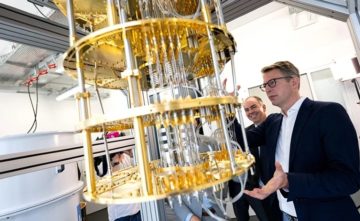

Pictures from Brueghel and Other Poems If you believe the hype, computers that exploit the strange behaviours of the atomic realm could accelerate drug discovery, crack encryption, speed up decision-making in financial transactions, improve machine learning, develop revolutionary materials and even address climate change. The surprise is that those claims are now starting to seem a lot more plausible — and perhaps even too conservative.

If you believe the hype, computers that exploit the strange behaviours of the atomic realm could accelerate drug discovery, crack encryption, speed up decision-making in financial transactions, improve machine learning, develop revolutionary materials and even address climate change. The surprise is that those claims are now starting to seem a lot more plausible — and perhaps even too conservative. In his now-classic 2018 book,

In his now-classic 2018 book,  The key to Philip’s personal appeal was his humor. As a boy, his favorite reading had been a famous joke book by a fellow Florentine, Arlotto Mainardi. As a man, Philip was quite a jester—and very jolly as well as a little zany. Writing about Philip in his Italian Journey, Goethe dubbed him “the humorous saint.”

The key to Philip’s personal appeal was his humor. As a boy, his favorite reading had been a famous joke book by a fellow Florentine, Arlotto Mainardi. As a man, Philip was quite a jester—and very jolly as well as a little zany. Writing about Philip in his Italian Journey, Goethe dubbed him “the humorous saint.” Germany Year Zero is the closest that Italian Neorealism came to reckoning with the psychic life of children. Made at the same time, Fireworks meditates on the generative possibilities of psychic and sexual shattering. In so many ways, Fireworks anticipates the explosion of the queer underground cinema that blossomed in the United States in the ’60s and in which Anger’s later film Scorpio Rising (1963) played a central role. Yet Fireworks is also a product of its own “queer time and place.”

Germany Year Zero is the closest that Italian Neorealism came to reckoning with the psychic life of children. Made at the same time, Fireworks meditates on the generative possibilities of psychic and sexual shattering. In so many ways, Fireworks anticipates the explosion of the queer underground cinema that blossomed in the United States in the ’60s and in which Anger’s later film Scorpio Rising (1963) played a central role. Yet Fireworks is also a product of its own “queer time and place.” To be British is a very complicated fate. To be a British novelist can seem a catastrophe. You enter into a miasma of history and class and garbage and publication—the way a sad cow might feel entering the abattoir. Or certainly that was how I felt, twenty years ago, when I entered the abattoir myself. One allegory for this system was the glamour of Martin Amis. Everyone had an opinion on Amis, and the strangeness was that this opinion was never just on the prose, on the novels and the stories and the essays. It was also an opinion on his opinions: the party gossip and the newspaper theories, the Oxford education and the afternoon tennis.

To be British is a very complicated fate. To be a British novelist can seem a catastrophe. You enter into a miasma of history and class and garbage and publication—the way a sad cow might feel entering the abattoir. Or certainly that was how I felt, twenty years ago, when I entered the abattoir myself. One allegory for this system was the glamour of Martin Amis. Everyone had an opinion on Amis, and the strangeness was that this opinion was never just on the prose, on the novels and the stories and the essays. It was also an opinion on his opinions: the party gossip and the newspaper theories, the Oxford education and the afternoon tennis. Memories are shadows of the past but also flashlights for the future. Our recollections guide us through the world, tune our attention and shape what we learn later in life. Human and animal studies have shown that memories can alter our perceptions of future events and the attention we give them. “We know that past experience changes stuff,” said

Memories are shadows of the past but also flashlights for the future. Our recollections guide us through the world, tune our attention and shape what we learn later in life. Human and animal studies have shown that memories can alter our perceptions of future events and the attention we give them. “We know that past experience changes stuff,” said  Human minds run on stories, in which things happen at a human level scale and for human meaningful reasons. But the actual world runs on causal processes, largely indifferent to humans’ feelings about them. The great breakthrough in human enlightenment was to develop techniques – empirical science – to allow us to grasp the real complexity of the world and to understand it in terms of

Human minds run on stories, in which things happen at a human level scale and for human meaningful reasons. But the actual world runs on causal processes, largely indifferent to humans’ feelings about them. The great breakthrough in human enlightenment was to develop techniques – empirical science – to allow us to grasp the real complexity of the world and to understand it in terms of