Steven Shapin in London Review of Books:

The tragedy of Thomas Kuhn’s life was to have written a great book. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions was published in 1962, when he was forty, and he spent the rest of his life distressed by its success. It has sold 1.7 million copies, and has been translated into 42 languages. Very few academic books sell in those numbers and scarcely any are still seen as state of the art sixty years after publication. Structure crosses disciplines. It is read by historians, sociologists and philosophers whose business is thinking about what science is and how it changes, and also by scientists with a reflective turn of mind. It is read by theologians pondering the differences and similarities between science and religion, and by anthropologists considering the characteristics of ‘Western’ and ‘non-Western’ thought. The book has insinuated itself into everyday language. Kuhn plucked the word ‘paradigm’ from linguistics – where it referred to the permutation of forms having a common root, like the conjugation of verbs or the declension of nouns – and repurposed it as the term for a key regulative resource in scientific inquiry, a concrete model of ‘the right way to go on’. Eventually, lots of things meant to be thought of as ‘innovative’ and ‘good’ were branded as ‘paradigm shifts’: new ways of producing factory-farmed chicken, the latest solution to the difficulties posed by Brexit for trade arrangements in Northern Ireland, the emergence of celebrity chef culture.

The tragedy of Thomas Kuhn’s life was to have written a great book. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions was published in 1962, when he was forty, and he spent the rest of his life distressed by its success. It has sold 1.7 million copies, and has been translated into 42 languages. Very few academic books sell in those numbers and scarcely any are still seen as state of the art sixty years after publication. Structure crosses disciplines. It is read by historians, sociologists and philosophers whose business is thinking about what science is and how it changes, and also by scientists with a reflective turn of mind. It is read by theologians pondering the differences and similarities between science and religion, and by anthropologists considering the characteristics of ‘Western’ and ‘non-Western’ thought. The book has insinuated itself into everyday language. Kuhn plucked the word ‘paradigm’ from linguistics – where it referred to the permutation of forms having a common root, like the conjugation of verbs or the declension of nouns – and repurposed it as the term for a key regulative resource in scientific inquiry, a concrete model of ‘the right way to go on’. Eventually, lots of things meant to be thought of as ‘innovative’ and ‘good’ were branded as ‘paradigm shifts’: new ways of producing factory-farmed chicken, the latest solution to the difficulties posed by Brexit for trade arrangements in Northern Ireland, the emergence of celebrity chef culture.

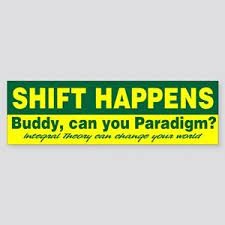

A New Yorker cartoon shows tramps leaning against a wall: ‘Good news – I hear the paradigm is shifting.’ Another has two men, their clothes billowing out in the wind, speculating that there must have been a ‘paradigm shift’. You can buy a bumper-sticker: ‘Shift Happens: Buddy Can You Paradigm?’

More here.