by Leanne Ogasawara

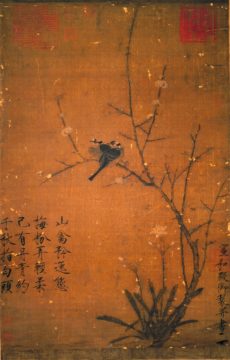

山禽矜逸態 梅紛弄輕柔 已有丹青約 千秋猜白頭

Mountain birds, proud and unfettered

Plum blossoms, pollen scattering softly

This painting but a promise

Of a thousand autumns to come

- The Painting

Nine-hundred years ago, a Chinese emperor painted a picture of a pair of birds in a plum tree –to which he then inscribed a poem in calligraphy of unsurpassed elegance, in a style all his own. It is interesting to consider that very few new styles of calligraphy emerged in China after the sixth century. But Emperor Huizong (r. 1101-25), while still only a young prince, created his own way of writing. Later dubbed the “slender gold” (瘦金體), it has been described by admirers as being writing like “floating orchid leaves,” or like “bamboo moving in the wind.” Or even more aptly, like “the legs of dancing cranes.” Detractors complained that the “skinny legs” are “too scrawny” to hold up the body, or “too bony”, like “a starving student in misfitting clothing.”

Whether one is partial to his characters or not, the fact remains that the “slender gold” style is probably the most famous –or maybe even the only– example in Chinese history of an emperor creating his own style of writing.

We see his four-line poem on the bottom left of the ink painting. Also there on the right of the delicately-drawn narcissus flowers, the emperor has signed his work –again, in that exquisite calligraphy like dancing cranes: “In the Xuanhe Hall, the Emperor drew this [picture].”

And what of the picture?

Well, we see two birds huddled together on a plum tree, under which grows a clump of narcissus. According to Chinese poetic convention, the plum and the narcissus are representative of the landscape of late winter and early spring. The plum, in particular, came to be admired for its capacity to blossom during extreme cold–even in the snow. Associated with pine and bamboo, both which remain green even in winter, the three became known collectively throughout East Asia as the “friends of the cold” (歲寒三友) and were considered to be symbols of fortitude and fidelity.

The plum pictured in the painting, however, is not actually a plum tree, but rather is what is called the wax plum (蠟梅), or Chimonanthus praecox. Native to China, the fragrant flowers are a cheerful bees-waxy yellow. It’s a favorite of mine.

In Japan, the narcissus (水仙), the plum (梅), the wax plum (蠟梅), and the camellia (椿) are affectionately called “the four flowers of winter” (雪中四花) and are symbolic of strength and overcoming adversity.

Huizong’s poem, however, is really about the two birds. Perched so closely together they appear as if one bird, we see them nestling together against the cold.

Huizong writes: “pollen scatters softly,” which reminds us of snow falling.

But what precisely are these “mountain birds” anyway?

The clue can be found in the last line of the poem, for which a closer translation of the last two lines might read something like this:

This painting but the promise

Of a thousand autumns upon our hoary heads —

Presumably two people –friends of the emperor?–have made a promise of some kind spanning a thousand autumns; that is to say, their promise will last until they are old, and their hair has turned white as snow. Hoary heads is written as “white head” (白頭). Looking at the painting, we immediately notice that the birds also have white feathers on their heads 白頭鳥. They are, in fact, unmistakably light-vented bulbuls (Pycnonotus sinensis). Sometimes called Chinese bulbuls (白頭翁), its name in Chinese includes the characters for “white head.” Looking up the bird on a Chinese bird site will reveal that this bird, known for its white head and brittle voice, was traditionally referred to in China as “white-haired old man.”

And so, looking at the picture of the two white-headed birds huddled together against the cold (pollen scattering like snow), we see them standing firmly together. Is it friendship or marriage? Well, a cursory google search will show that traditionally Chinese bulbuls symbolized “married couples reaching old age together.”

This is not a Japanese convention.

Many –if not most?– of the poetic symbols in Japanese poetry do have a link to China, but not the bulbuls. And so being a Japanese translator, I almost missed it. In Japan, mandarin ducks are the conventional symbol of married fidelity, which is the same throughout East Asia. In Huizong’s poem, though, it is the pair of bulbuls that refer to a married couple reaching old age together. So, while it is not clear for what occasion the emperor created this work, I think it is safe to say that the promise implied was of a thousand autumns of love and fidelity. This is a wish for a couple to be blessed in growing old happily together like the birds in the picture.

It might have helped if I had known about the Han dynasty literary figure and poet Zhou Wenjun who is said to have written a poem titled Song of Hoary Heads (白頭吟) about a time when her husband threatened to take a concubine and she wrote “the song of the hoary head”

願得一心人 白頭不相離

I wish for a lover in whose heart I alone exist

Unseparated till the end of time (until our hair turns white).

- The Translation

These days, as I find myself on the cusp of retiring from my career in translation, what remains with me above everything else is the puzzle-like challenges involved in translating poetry across cultures and time periods.

What a dazzlingly daring thing to do: to translate a poem from one language into a poem in another. Even a poem of only three or four short lines in English can be something to fully occupy a person’s mind and heart. I have worked some on haiku, and compared to the longer modern freestyle verse forms, I think the short forms are much harder to get right. The challenge is great but so are the rewards.

Poems embedded in other poems, rebuses, puzzles and word play….

Choices must be made. Something will always be lost.

Translation is always treachery!

A thankless job. For when the translator gets it right, she is like air– that is, the translator’s role should fade into invisibility. But, when she makes a mistake? Well, it could haunt them for the rest of their lives– and beyond! When I was an undergraduate at Berkeley studying philosophy, the late great Hubert Dreyfus would rail against Heidegger’s translator.

“What has the translator done now?” He would scream, grabbing his German edition. That was the first time I stopped to think about what can happen in translation.

I am currently reading novels with translators as their protagonists. I just started Nina Schuyler’s The Translator—and in the book there are so many scenes showing the Japanese translator rehearsing possible translations for words,

She pushes aside her notebook and opens a book of Komachi’s poetry. Hana no iro faturi ni keri na itadura ni

Hanne translates: Color of the flower has already faded away. Or she could translate it: Cherry blossoms pale after long rain. Or, The flowers withered/ Their color faded away. Or, Flowers fading. In the long rain of regret. She moves on to the next verse, then the next.

Japanese, like Chinese is a high context culture language. Speech in a high context culture such as Japan and China, or France and Spain, will make use of many types of non-verbal communication, such as body language and tone. It is more nuanced. Understood context is not ostensibly stated aloud. This makes it more indirect, being based on communal sensibilities. In contrast, low-context languages often developed for use across differing cultures. Examples include Bahasa Indonesia, American English, German, and Nordic languages. In these low-context cultures, there is a preference for direct, concise, and straight-forward communication since often these languages served as market or business languages across regions.

One could argue that in addition to being less ambiguous, communication in low-context languages is –by necessity– more limited.

So in Huizong’s poem there is embedded information. Of course, the same could be said of poems about red roses in English. The poet wouldn’t necessarily need to explicitly explain that they evoke –and connote– romance. But in high context cultures, this is much more intense.

In a translation, does the translator need to include this embedded information? Ideally, yes. That is why, I would be very tempted to do so adding one final word to the poem (though some might say I am overstepping?)

Mountain birds, proud and unfettered

Plum blossoms, pollen scattering softly

This painting but a promise

Of a thousand autumns to come–together

Did I mention I have been playing around with this poem for over twenty years?

I am embarrassed to admit that about ten years ago, I put this attempt online:

Mountain birds, unfettered and proud;

Plum blossom pollen, soft and scattering softly.

This painting– but a promise

Of a thousand autumns to come

Painting mountain birds

It was pure conceit, which was easier to get away with in the days before the Internet made all this information readily available!

- One last Word about the Emperor

Returning to Emperor Huizong, let’s try and read the man by his handwriting.

The first impression that strikes us is that despite the sense of speed and pleasing movement that these “dancing crane legs” convey, there is also a precision and something almost methodical about the writing, especially in the endings and connections between strokes. Like jade, there is a hardness, coolness, and resonance as well. It conveys erudition and great personal style. Huizong is not known as the “aesthete emperor” for nothing!

Is there anything else we can say? After the immediate impression of precision wears off, perhaps the strongest impression that I am left with is a sense of fancifulness and a willingness to ignore conventions for the sake of beauty. Indeed, Huizong consciously broke the rules of writing to achieve his unique new style.

We can see this, for example, in the very first character of mountain 山 where the third stroke is not written according to the conventional rules by passing through the horizontal stroke.

I am suspicious of that second stroke as well.

Perhaps it was this same part of his personality–this attentiveness to beauty– that would explain how this emperor who had special tunnels dug under the palace in order to walk the streets of Kaifeng undetected could continue obliviously writing his poetry and lavishly spending on the arts as his country teetered on the edge of disaster. For it was only a matter of time before he would see his glorious capital plundered and he, along with two hundred years of Song dynasty imperial art carted off as war-booty to Manchuria where the art works would be scattered, and many lost forever.

Captured by the Jurchen invaders, our Emperor was to end his days alone in cold captivity not far from present-day Harbin. There remains one lonely poem supposedly written by the Emperor, as he traveled north–a captive of the Jurchens. Seeing a pair of swallows in an apricot tree, he wondered if he would ever see his palace again.

I attempt the last half of the poem in free ranging English below

燕山亭·北行見杏花

北行見杏花裁剪冰綃,輕疊數重,淡着燕脂勻注。新樣靚妝,豔溢香融,羞殺蕊珠宮女。

易得凋零,更多少無情風雨。愁苦!問院落淒涼,幾番春暮?

憑寄離恨重重,這雙燕何曾,會人言語?

天遙地遠,萬水千山,知他故宮何處?怎不思量,除夢裏有時曾去。無據,和夢也新來不做。

Yanshan Pavilion

[ ]

I tell of the sorrow of partings upon partings

To a pair of swallows

Will they speak my language

Beneath these boundless heavens

Separated by countless rivers and countless mountains

Could these swallows find my palace, so far away?

For how can I ever forget that old Palace?

Now I visit only in my dreams

And yet all alone

Sometimes I am even unable to dream

I love the poem so much. And yet, I probably can barely grasp its meaning. I am only seeing it through the lens of Japanese translations. Already, I am once removed. Then to try and create an English version is to be twice displaced.

Displaced and disoriented. So many early translations of Japanese and Chinese texts entered European language vis-à-vis the English translations, which were themselves dripping in the world-view of the translator. Think, for example of Arthur Waley’s version of the Tale of Genji that made readers feel almost like they were in Victorian England—or of Fenollosa and Pound’s early “translations” of Chinese or Japanese.

This is not a complaint since these early translations are quite wonderful.

In my favorite novel so far with a translator as protagonist, Idra Novey’s Ways to Disappear, a translator travels to Rio to find her client, a Brazilian cult author, whose gone missing. What I loved best about Novey’s gorgeous book (did I mention she is a poet?) is that the translator in the story is an aspiring writer. This is a transformation that happens as the translator searches for the missing author to whom she has devoted her life. In Brazil, she begins to shake off the translator’s position of being “available yet silent,” where there is “no obvious spot for her to put herself,” to begin writing her own prose in her journal. So, then, this is a search of self-discovery?

The handsome son of the missing author asks her, “Do you write too?” when he spots her open journal on the bed. She says, “Oh, no, that’s nothing.” But later remarks,

traduttore, tradittore—that tired, tortured Italian cliché. If only she’d been born a man in Babylon when translators had been celebrated as the makers of new language. Or during the Renaissance, when translation was briefly seen as a pursuit as visionary as writing. She would have been in her element then. During the Renaissance, no translator had to apologize for following her instincts to champion the work of one of the most extraordinary, under-recognized writers of her time.

Oh how the mighty have fallen?

++

- For more on Chinese paintings and rebuses, see this article. And for a short post about plum blossom imagery in Japan, please see my Substack on plum blossoms

- For more about Books featuring translators (Do you have a favorite?) please see my Substack post Books About Translators.

- For more on translation, please see my 3QD post Japanese and the Beginner’s Mind and Trials In Translation: The Monk Dōgen And His Birds