by Michael Abraham

She used to roll up to my house late at night, in her green pickup truck, smoking a Parliament out the window and blasting The Strokes. I was seventeen. I would climb in, and we would drive through my neighborhood much too fast, her weak, amber headlights illuminating only the nearest spot of road. We would talk about the day, about our friends at Catholic school, about whatever. It wasn’t so much about the talking. Even then, at that early time in our friendship, it was about the being together, often the being together in silence. We grew up outside of Seattle, and so there were woods aplenty, and we would pull off on some country highway, and she would take out her straight-tube bong, and we would rip it while Julian Casablancas crooned, Some people think they’re always right. Others are quiet and uptight. Others, they seem so very nice-nice-nice, oh! Inside they might feel sad and wrong, oh, no! We liked that song, probably because inside we felt so sad and so wrong, so unfit as subjects in the world we inhabited. Two misfit kids in a green pickup truck in the dead of night. Then, she would start the truck back up, and we would drive listlessly through the dark vigil of the trees on either side of the road, winding this way and that, singing along or lapsing into thought. I would stare out the window and watch the shadows roll by, and I would feel, for a moment, impossible and effervescent. I fell in love with her on these long, circuitous drives through the night. I came to believe very strongly in her, in the vibrancy of her presence, in some curious and ineffable extra that she had to her which other people did not have. She was imposing, even then, as she is now—but gentle inside, just.

For my birthday that year, she gave me a copy of Crush, Richard Siken’s first book of poetry. Years later, I would meet Siken at a signing in New York, and I would ask him to do something a bit odd, which was to sign the book, not on the title page, but under a poem called “Unfinished Duet.” He would ask why, and I would respond, “A dear friend gave me this book when I was seventeen, and I read ‘Unfinished Duet,’ and now I study poetry at NYU,” which was an entirely true genealogy. Siken smiled knowingly, and he wrote, beneath the poem, “I [illegible] like this [illegible] little poem. I couldn’t finish it so I wrote a whole ‘nother book. RS.” This was probably a gentle nudge to get me to buy the book for which the signing was being held, but I was a college student and broke, so I left with my newly signed copy of Crush and did not buy War of the Foxes until a long time after. Read more »

But only now can I tell you about the texture of the world Miyazaki created—for instance, the flickering neon signs advertising pork on the lane where Chihiro’s parents first turn into hogs. During one recent rewatch in a double feature with Howl’s Moving Castle, I noticed the choice to dress Yubaba, the witch who puts Chihiro to work, in gaudy Western attire despite her Asian-bathhouse surroundings, similar to Miyazaki’s later rendition of Howl’s Witch of the Waste; in both cases, he uses the women’s occidental stylings to highlight their tasteless greed. On another occasion, I realized that Rin, the young bathhouse worker who becomes Sen’s friend and guide, shares a resemblance to Lady Eboshi in Princess Mononoke and Satsuki from My Neighbor Totoro—they all fit the Ghibli big-sister archetype. Only in rewatching did I start to see and appreciate the connections between characters in the Miyazaki Cinematic Universe.

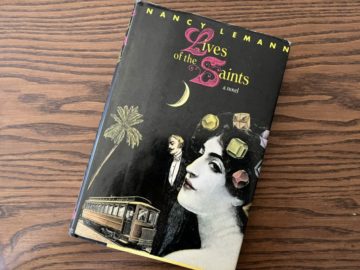

But only now can I tell you about the texture of the world Miyazaki created—for instance, the flickering neon signs advertising pork on the lane where Chihiro’s parents first turn into hogs. During one recent rewatch in a double feature with Howl’s Moving Castle, I noticed the choice to dress Yubaba, the witch who puts Chihiro to work, in gaudy Western attire despite her Asian-bathhouse surroundings, similar to Miyazaki’s later rendition of Howl’s Witch of the Waste; in both cases, he uses the women’s occidental stylings to highlight their tasteless greed. On another occasion, I realized that Rin, the young bathhouse worker who becomes Sen’s friend and guide, shares a resemblance to Lady Eboshi in Princess Mononoke and Satsuki from My Neighbor Totoro—they all fit the Ghibli big-sister archetype. Only in rewatching did I start to see and appreciate the connections between characters in the Miyazaki Cinematic Universe. I picked up Nancy Lemann’s Lives of the Saints from a sidewalk pile in Greenpoint in October 2020, just a few minutes before it started raining in sheets. I read the novel in one sitting when I got home. The next day, I lent it to a friend with whom I was crashing for a few weeks. She returned it twenty-two months later, at the beach. Before we even left Fort Tilden I found myself lending it out to another friend. I’m not very generous with books, to be honest, but for some reason, this novel, like an early-aughts chain email, demands to be forwarded. It is a short book, which makes it a good loan to a friend, because you can jointly anticipate a sense of accomplishment. And it may then become a field guide to certain shared experiences of Youth—allowing you both to observe, for instance, on a summer night when everyone around you is having Breakdowns, that this is exactly like Lives of the Saints.

I picked up Nancy Lemann’s Lives of the Saints from a sidewalk pile in Greenpoint in October 2020, just a few minutes before it started raining in sheets. I read the novel in one sitting when I got home. The next day, I lent it to a friend with whom I was crashing for a few weeks. She returned it twenty-two months later, at the beach. Before we even left Fort Tilden I found myself lending it out to another friend. I’m not very generous with books, to be honest, but for some reason, this novel, like an early-aughts chain email, demands to be forwarded. It is a short book, which makes it a good loan to a friend, because you can jointly anticipate a sense of accomplishment. And it may then become a field guide to certain shared experiences of Youth—allowing you both to observe, for instance, on a summer night when everyone around you is having Breakdowns, that this is exactly like Lives of the Saints. University College, Oxford,

University College, Oxford, It’s not possible. There must be a rational explanation. Surely, you say to yourself, there is a logical justification. But no matter how hard you look, there is no answer that aligns with what you know about reality. With the magician’s final deception, the last act of their trick, the audience encounters the impossible: a bird appears out of thin air, a person begins to levitate and fly, or private thoughts are read like pages in a book. Magicians do things spectators know aren’t possible. This is the power of illusion. As the American magician Simon Aronson put it in 1980: ‘There’s a world of difference between a spectator’s not knowing how something’s done versus his knowing that it can’t be done.’ But magic is not only an encounter with the impossible. It is also an encounter with the perceptual machinery we use to assemble reality.

It’s not possible. There must be a rational explanation. Surely, you say to yourself, there is a logical justification. But no matter how hard you look, there is no answer that aligns with what you know about reality. With the magician’s final deception, the last act of their trick, the audience encounters the impossible: a bird appears out of thin air, a person begins to levitate and fly, or private thoughts are read like pages in a book. Magicians do things spectators know aren’t possible. This is the power of illusion. As the American magician Simon Aronson put it in 1980: ‘There’s a world of difference between a spectator’s not knowing how something’s done versus his knowing that it can’t be done.’ But magic is not only an encounter with the impossible. It is also an encounter with the perceptual machinery we use to assemble reality. My colleagues Gary Gerstle and

My colleagues Gary Gerstle and  L

L Sad times are inevitable, and most people eventually rally. But clinical depression is different, and more brutal. All sense of well-being evaporates; life can seem not worth the trouble. According to one estimate, more than 60% of people worldwide who have attempted suicide have a depressive disorder (

Sad times are inevitable, and most people eventually rally. But clinical depression is different, and more brutal. All sense of well-being evaporates; life can seem not worth the trouble. According to one estimate, more than 60% of people worldwide who have attempted suicide have a depressive disorder (

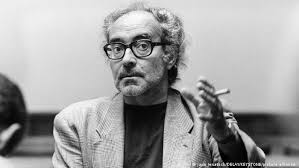

On the 13th September 2022, Jean-Luc Godard, the Franco-Swiss film-director, film-poet, film-philosopher, died at the age of 91. One of the most imaginative, rebellious, truly courageous artists on this planet whose existence, in more ways than can be enumerated in language, changed the face of our modernity, decided to end his life through assisted suicide, which is a legal practice in Switzerland, the country he had been living in since 1976, and in which he had spent his youth. He was not ill, ‘but exhausted’. In addition to everything else, his last action resonates with a magnitude that is as powerful as a political stand as it is as a last demonstration of a personal ethics which can be summarised as: moral integrity or nothing. A moral integrity, which he brought to bear indefatigably over the course of a lifetime in pursuit of freedom, resolution and independence – at whatever price.

On the 13th September 2022, Jean-Luc Godard, the Franco-Swiss film-director, film-poet, film-philosopher, died at the age of 91. One of the most imaginative, rebellious, truly courageous artists on this planet whose existence, in more ways than can be enumerated in language, changed the face of our modernity, decided to end his life through assisted suicide, which is a legal practice in Switzerland, the country he had been living in since 1976, and in which he had spent his youth. He was not ill, ‘but exhausted’. In addition to everything else, his last action resonates with a magnitude that is as powerful as a political stand as it is as a last demonstration of a personal ethics which can be summarised as: moral integrity or nothing. A moral integrity, which he brought to bear indefatigably over the course of a lifetime in pursuit of freedom, resolution and independence – at whatever price.