by Ada Bronowski

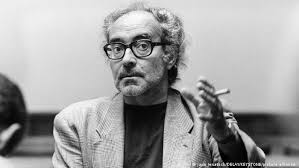

On the 13th September 2022, Jean-Luc Godard, the Franco-Swiss film-director, film-poet, film-philosopher, died at the age of 91. One of the most imaginative, rebellious, truly courageous artists on this planet whose existence, in more ways than can be enumerated in language, changed the face of our modernity, decided to end his life through assisted suicide, which is a legal practice in Switzerland, the country he had been living in since 1976, and in which he had spent his youth. He was not ill, ‘but exhausted’. In addition to everything else, his last action resonates with a magnitude that is as powerful as a political stand as it is as a last demonstration of a personal ethics which can be summarised as: moral integrity or nothing. A moral integrity, which he brought to bear indefatigably over the course of a lifetime in pursuit of freedom, resolution and independence – at whatever price.

On the 13th September 2022, Jean-Luc Godard, the Franco-Swiss film-director, film-poet, film-philosopher, died at the age of 91. One of the most imaginative, rebellious, truly courageous artists on this planet whose existence, in more ways than can be enumerated in language, changed the face of our modernity, decided to end his life through assisted suicide, which is a legal practice in Switzerland, the country he had been living in since 1976, and in which he had spent his youth. He was not ill, ‘but exhausted’. In addition to everything else, his last action resonates with a magnitude that is as powerful as a political stand as it is as a last demonstration of a personal ethics which can be summarised as: moral integrity or nothing. A moral integrity, which he brought to bear indefatigably over the course of a lifetime in pursuit of freedom, resolution and independence – at whatever price.

His decision has opened the floodgates to an open debate for a reappraisal of the right to assisted suicide across Western European media, and renewed pressure on institutions. Death, the possibility of suicide, the preparation for and incorporation of death in life have been constant companions throughout a body of work that spans over sixty years of filmmaking, and around 130 films as credited on Godard’s IMDB page, though word on the street is that it is more like 140 – scholars and archivists have their work cut out for them, and we can at least look forward to a great deal of publications and releases of material that was kept unseen or undistributed for a myriad of reasons, one of them being that Godard did not consider them of interest. He was a perfectionist, and therefore regarded everything once done, practically a failure and everything yet to do, a necessary call to continue working. Making a film is like cooking, he said once in a conversation with the great French novelist Marguerite Duras, (and incidentally author of a rare and refined cookbook), you can’t pretend your soggy noodles are a success.

So much has already been said and written about Godard, but with Godard, much is very little or, to say it more like he would, fractal. His films, borne out of his early film critiques from the 1950s, in the Cahiers du Cinema, in which he lambasted commercial cinema for lying about life, love and social relations, were, by explicit contrast, concerned with showing and saying (two different actions) the truth. And yet, the very nature of the eye of the camera, which cuts out a slice of space and time out of space-time and puts it on a pedestal of signification, all at once disables the capacity of the film to reach any totalising universal truth. There is only a truth, that is, a multiplicity of truths. Godard’s films have this in common: the multiplication of focal points and the accumulation of truths derived from each one of them.

His limitless creativity is fuelled by the enraged awareness that only from the ungraspable multitude might something close to a truth rise out of the chaos of individual lives. He has, for instance, a fascination with the starry sky, from the Dante line, essentialised in translation, that he puts in the mouth of Michel Piccoli in Contempt (1963): ‘Déjà la nuit contemplait les étoiles…’ (‘Already the night beheld the stars’), to the often-filmed close-up on a coffee cup whose melting foam on the black surface becomes the moving image of galaxies traversed by constellations.  Such images, more than words (the image is always more powerful), are reminders that the infinitely bigger and the infinitely smaller are the real frames of our lives. Cinema, he would say, is the art of extremes.

Such images, more than words (the image is always more powerful), are reminders that the infinitely bigger and the infinitely smaller are the real frames of our lives. Cinema, he would say, is the art of extremes.

There is the frame and there is what is out of the frame and there is the spectator (so often appealed to directly through regular breaks of the fourth wall in Godard’s films) and so there is always a to-and-fro between what escapes the frame and what escapes the spectator and what the spectator grasps and what the frame uncovers. In that in-between, Godard has ceaselessly invented how to create a meaning greater than the juxtaposition of two images.

He was a poet who wrote with the camera, a creator of forms, wary of language and of the polysemy of signs, but conscious of their inescapable presence in social life and their source of inevitable misunderstanding and in most cases, the cause of miserable endings. A recent film, Goodbye to Language, a 3-D experiment from 2014, pushes the boundaries of mutual incomprehension to end with only the dog, whose thoughts are narrated through a voice-off, as the being who still makes any communicable sense. He was a pessimist, i.e., a realist. But his pessimism was not brought about by old age. Godard was never old, or perhaps was never young.

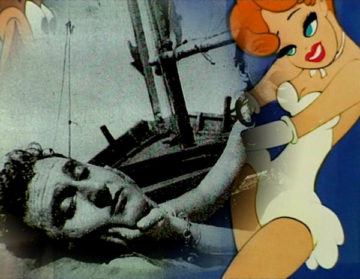

The question of what someone means when they say what they say is an omnipresent question in Godard’s cinema, encapsulated – till the end of time! – in the last scene of his first film, Breathless, from 1960, with Jean-Paul Belmondo muttering in his dying breath: ‘C’est vraiment dégueulasse.’ (It’s really disgusting, or it’s not fair – so much of the subtleties of French in Godard get lost in translation). Jean Seberg asks: ‘What did he say?’ A policeman replies: ‘He said, you are disgusting’ – which is, of course, not what Belmondo said. And Seberg (pictured) asks the camera: ‘Qu’est-ce que c’est dégueulasse?’, (‘What is disgusting?).

Godard’s cinema, encapsulated – till the end of time! – in the last scene of his first film, Breathless, from 1960, with Jean-Paul Belmondo muttering in his dying breath: ‘C’est vraiment dégueulasse.’ (It’s really disgusting, or it’s not fair – so much of the subtleties of French in Godard get lost in translation). Jean Seberg asks: ‘What did he say?’ A policeman replies: ‘He said, you are disgusting’ – which is, of course, not what Belmondo said. And Seberg (pictured) asks the camera: ‘Qu’est-ce que c’est dégueulasse?’, (‘What is disgusting?).

As the Byzantine Neo-Platonist philosopher Gemistos Plethon once said, (at a council meeting in Florence in 1439, having arrived from Constantinople in an attempt to convince the Western Christians to help save the Byzantine Christians about to be destroyed by the Ottomans): the truth resides in the million shards of Aphrodite’s broken mirror. Godard is very much the man who went in search of those shards of reflecting truths (there are mirrors everywhere in Godard). Plethon comes to mind, not only because of his pessimistic take on the Platonic quest for perfection, which encapsulates so well Godard’s working life, but also because Plethon is the man who brings wisdom to the West, warning the West of the end of an era, perhaps even of a civilisation. Godard too has been playing the prophet of endings, the end of cinema, the end of meaning, the end of meaningful work.

In the obituaries that have been published, he has been compared to Picasso, first because he has fulfilled, like Picasso in his day, the role of an absolute reference point for all the arts, being himself a ‘total artist’ whose creation of forms influenced architecture, fashion, music, the visual and performance arts, as well as film (Jim Jarmusch, Leox Carax – even Quentin Tarantino). The comparison also extends to a Picasso-esque periodisation of his body of work, with the Anna Karina years, the Maoist-militant years, the video years etc. But another way of classifying his filmography would be to say that there are two kinds of film by Godard, those that you can watch but do not understand, and those you cannot watch but can understand.

However, to stay true to the spirit of Godard, we should not try to classify and divide, but rather unify and hold together what was always meant to be the expression of an integral whole. For there is no division between the man and the artist, the creator and his life, itself lived as accompanying the creation of cinematic forms of life; he only ever lived his life as crystalised in the film Vivre Sa vie (My Life to Live) from 1962. It made for a difficult life, punctuated with violent feuds with past friends, perhaps most famously with François Truffaut who called him ‘a shit on a pedestal’ in one of the most breath-taking friendship break-up letters of the 20th century[1]. But in a short preface which Godard was invited to write to the 1988 edition of Truffaut’s letters[2], (Truffaut, who had died of a brain tumour in 1981), Godard writes with a hauntingly God-like wisdom ‘François is perhaps dead. I am perhaps alive. There is no difference.’ Time is nothing, disputes are nothing, what counts is the existence of connection, having tried to do something, having tried to express something.

Despite his misanthropic aura, throughout his films and in interviews, Godard’s sensitivity, what he calls, in different films the need for ‘tendresse’, which is not quite the English tenderness, but something in between affection, softness and loving protection, forms the basis for the possibility of a connection, if not love. He was a unique, idiosyncratic, total (body and soul) creator. Idiosyncrasy: integrity for those who have genius.

He went from a fireworks decade, the 1960s, in which he created bombshell after bombshell, from his first film A Bout de Souffle, (Breathless), which became an international, overnight sensation to unsurpassable works of art such as Vivre Sa vie, (My Life to Live), Pierrot le Fou, Contempt, Masculin Féminin, Bande à Part, Two or Three Things I Know About Her, to films which became more explicitly experimental in their connection to linear narrativity. What we tend to call experimental in the case of Godard, is not a pretentious over-cleverness, but merely a consistent line of thought which pushes forward the limits of the visually bearable, breaking each time anew with what was acceptable till that point, and thereby opening new windows of meaning. In this respect, Godard has never been but consistently discontinuous – the oxymoron being his favourite mode of reflection.

What was so revolutionary with Breathless in 1960, more even than in François Truffaut’s The Four Hundred Blows from 1959, (more emotionally rather than plastically radical, though together, these two films mark the beginning of the Nouvelle Vague), was the upheaval in form: the constant invention, frame after frame, of ways of being out of step with the linearity of sound and image, and yet expressive of communicable meaning.

From Breathless onwards, every film, however different – indeed, necessarily different, since each is a further exploration of the edge of what is possible – breaks with linearity and mainstream habits of continuity. And yet within that breach – between sound and image, between what is shown and what the story is about, between dialogue and externalised interior monologue, between gravity and silliness – there occurs the magic of Godard’s idiosyncratic creation of meaning. It is the communication of something greater than the images and the dialogue can convey in their sequential order, and which rises out of the contradiction inherent both in the image and in the sound. It is a Hegelian enactment of Aufhebung that lifts up through the viewing of the film.

Cinema, as Godard used to say, ‘is truth 24 times per second’. That is why to see a film by Godard, you have to watch it many times over, realising each time something more about it. And to grasp the complexity, the attention to every detail, every postcard on the wall, every strip of colour, you must pause the film frame by frame, go back, go forward, go back again. The layers of meaning, the hidden allusions, the beauty of a mathematician’s geometrization of space are mind-blowing. It makes for some of the most intense filmic experiences there are – and all without blood or gore or flying green aliens. It is also life-changing. You can never go back to the innocence of carefree cinematic entertainment if you have ever really watched a film by Godard. For those who were raised on his cinema (like the author of these words) and for those who at some point in their path entered his world, he has made cynics of us all, who know that real beauty is to be found in an already splintered mirror.

There is no continuity in true art because continuity is a lie. It is Godard’s great battle against television and the cinema that submitted to televisual norms – and to which our current Netflix addicted world has largely sold its body and soul. The more the world tipped towards the illusion of continuity, the more Godard’s cinema took its own lonely path, constructed through a uniquely Godardian internal consistency. His films thus morphed into what, on the surface, may appear as a move from the watchable to the unwatchable.

Films such as For Ever Mozart (which in French sounds like Faut Rêver Mozart: Got to Dream Mozart) from 1996 might appear like an extra-terrestrial being in comparison with a Hollywood production: in it, a troupe of actors try to stage Marivaux (the 18th century playwright of games of lightness and love) inside war-torn Sarajevo, whilst at the same time a film director plans to shoot a porn film, itself crossed by scenes of accumulated dead bodies on a beach, closing on a scene in which a period-dressed pianist plays Mozart. The film is far madder than this brief description, which can barely do it justice. The images bore holes into your mind whilst the titillating idea that there is a deeper meaning just round the corner from where you are standing, or rather helplessly sitting, both infuriates and charges you with an electric desire to watch more.

But it would be a mistake to consider that For Ever Mozart or already Sauve qui peut (la vie), (less fantastically translated as Every Man for Himself), from 1980, or First Name: Carmen from 1983 are in rupture with the first sensational films, such as Bande à Part (1964) or Contempt, starring the sulphurous Brigitte Bardot from 1963. The earlier films were box office hits and the latter became niche. But it is the same inner and outer worlds that Godard has relentlessly scoured. They all pursue the same holy grail: fragments of the truth of our lives in our world as it really is.

What kind of a world? A world of prostitution, of adoring lovers that become pimps, of lost-souls, of porn and murder, death and probably suicide, of greed and corruption, of total incomprehension between men and women, and above all, of suffering, inextricable suffering. If there is love, it lasts but a moment, and probably only within a work of art.

What Godard dared to represent was the state of atomisation of the world. It is there in the early films, for instance in Masculin Féminin from 1966, as simply demonstrated as a scene in a café in which two friends, (played by Jean-Pierre Léaud and Michel Debord, pictured) are reading together an article about a new American singer they have not heard of (Bob Dylan!), when all of a sudden the camera shows a whole other unknown side of the café, where Michel Debord is now standing asking a girl if he can take some sugar from her table.  There is no movement from frame A to frame B, only the sudden realisation the two friends are not alone in a small space, but that there is a wider world populated by other people the characters themselves were in fact absorbed by, whilst we thought they were talking about Dylan. Debord’s character had been eyeing the girl all along. But it is only once he returns to his table, and we return to the narrowness of frame A (after spending time in frame B), that we understand what was really happening in the previous shot, since he comments on the perfection of the girl’s breasts as though they had spoken about them before (though they hadn’t). The point is not the girl, it is Godard’s way of making the spectator realise that we do not understand anything of what is actually happening before our very eyes.

There is no movement from frame A to frame B, only the sudden realisation the two friends are not alone in a small space, but that there is a wider world populated by other people the characters themselves were in fact absorbed by, whilst we thought they were talking about Dylan. Debord’s character had been eyeing the girl all along. But it is only once he returns to his table, and we return to the narrowness of frame A (after spending time in frame B), that we understand what was really happening in the previous shot, since he comments on the perfection of the girl’s breasts as though they had spoken about them before (though they hadn’t). The point is not the girl, it is Godard’s way of making the spectator realise that we do not understand anything of what is actually happening before our very eyes.

It is that same idea only magnified to epic dimensions that fuels the huge work titled Histoire(s) du Cinema, an eight-episode film created from 1988 to 1998, totalling more than four hours composed entirely of fragments of different films and photographs with Godard’s own crepuscular voice-off, not narrating, but commenting over the images in disjointed words of wisdom and quotations from poets and philosophers. You can go into a trans and lose yourself in the film, or you can listen and pause, rewind or fast forward and slowly empathise with the cinematico-poetic project whose closest model is On The Nature of Things by the 1st century BC poet-philosopher, Lucretius.

In his epic poem, Lucretius recounts through sublime images the principles of atomistic philosophy. He shows the necessity that all things (wars, loves, volcanic eruptions…) be reduced to chance meetings between very small and insignificant particles. It follows that there are infinite and multitudinous worlds we have no control over and will never know. Same project, same result only using 20th century photography in Histoire(s) du Cinema. Through the choc of the juxtaposition of images, of war and weddings, courtship and murders, films-stars and the Holocaust, colour and black-and-whites, poetry and silence, massacres and sex, the starry sky and the first films by the brothers Lumière – all the images we are familiar with are nothing but tiny insignificant fragments of a multitude whose limits, if they exist, we are ignorant of. Any connection is as fragile as the meeting of two atoms, ready to disaggregate at any moment.

and silence, massacres and sex, the starry sky and the first films by the brothers Lumière – all the images we are familiar with are nothing but tiny insignificant fragments of a multitude whose limits, if they exist, we are ignorant of. Any connection is as fragile as the meeting of two atoms, ready to disaggregate at any moment.

Our everyday lives are nothing but imminent moments of disaggregation. It is these moments that Godard has been capturing since his first films. The incomprehensible moment when love turns to indifference, fun into death, a married woman sells her body, a city becomes a slum. All unfathomable, all part of a network which, Lucretianly, hangs upon meaningless connections governed by a random swerve that has nothing to do with anyone or anything.

There have always been two conceptions of aristocracy. The one theorised by Plato as that of wisdom and action in wisdom, and that favoured by the Judeo-Christian tradition, that of the dumpy parasite. Godard was, is, a philosopher-king, in the true Platonic tradition. An apogee of unflinching strife for understanding, improvement, unforgiving (to himself and others) in a constant attempt to reach the right, the good, the perfect, all the while humbly acknowledging perpetual failure and refusing – as Plato had foretold – the place of command. Godard gave his Oscar to his accountant and shirked from honours and accepting prizes. For those from planet Plato, a king, maybe a God, has died, God(ard) is dead, long live Godard.

[1] See Antoine de Baecque’s essay and Truffaut’s letter translated into English in A. Bronowski, Dear Friend, You Must Change Your Life, Bloomsbury 2020, p.187-200.

[2] F. Truffaut, Correspondance, Hatier : Livre de Poche, 1988.