by Ethan Seavey

My last night in the house on Euclid Avenue will go one of two ways:

My last night in the house on Euclid Avenue will go one of two ways:

A. When I climb through a window in my bedroom (which will no longer be my bedroom tomorrow) and onto the flat roof outside in order to smoke the very last bowl of cannabis in my home (which will no longer be my home tomorrow), a moth will seize the opportunity to fly into the room.

B. Scenario A won’t happen.

The chances of scenario A occurring can be described as somewhat unlikely but certainly possible. This possibility is mostly blamed on the size and age of the window. It is about thirty square feet in total. This is a blessing in the fact that I can fit through the window easily and even sit in the frame comfortably if it’s raining. But in August its great size becomes a problem. A greater surface area gives moths a greater chance of entering my room. Moths are rather persistent when they’re around, but they’re often exploring other lights. So, they’re rare but not uncommon. I saw one a few days ago, but I haven’t seen one since. When I do see moths, I see them in August. It is August. It is August 26. I leave for New York in late August, August 27, the 27th, August 27, I’ll fly from Chicago to New York on August 27, which is tomorrow, it’s already here. Read more »

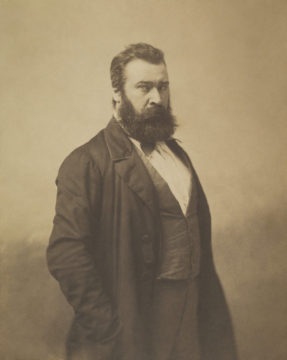

Jean-François Millet, a Frenchman, frowned beneath his full beard as he lay dying in Barbizon. It was 1875, and he was not to be confused with Claude Monet—not yet—who would later paint water lilies and haystacks but wasn’t, in 1875, rich and famous; on the contrary—and in spite of Édouard Manet’s having just painted him painting from the vantage of a covered paddle boat, appearing pretty well-to-do in the process—he was barely getting by.

Jean-François Millet, a Frenchman, frowned beneath his full beard as he lay dying in Barbizon. It was 1875, and he was not to be confused with Claude Monet—not yet—who would later paint water lilies and haystacks but wasn’t, in 1875, rich and famous; on the contrary—and in spite of Édouard Manet’s having just painted him painting from the vantage of a covered paddle boat, appearing pretty well-to-do in the process—he was barely getting by.

As with game theory, I also attended some courses in Berkeley in another relatively new subject for me, Psychology and Economics (later called Behavioral Economics). In particular I liked the course jointly taught by George Akerlof and Daniel Kahneman (then at Berkeley Psychology Department, later at Princeton). I remember during that time I was once talking to George when my friend and colleague the econometrician Tom Rothenberg came over and asked me to describe in one sentence what I had learned so far from the Akerlof-Kahneman course. I said, somewhat flippantly: “Kahneman is telling us that people are dumber than we economists think, and George is telling us that people are nicer than we economists think”. George liked this description so much that in the next class he started the lecture with my remark. On the dumbness of people I later read somewhere that Kahneman’s earlier fellow-Israeli co-author Amos Tversky once said when asked what he was working on, “My colleagues, they study artificial intelligence; me, I study natural stupidity.”

As with game theory, I also attended some courses in Berkeley in another relatively new subject for me, Psychology and Economics (later called Behavioral Economics). In particular I liked the course jointly taught by George Akerlof and Daniel Kahneman (then at Berkeley Psychology Department, later at Princeton). I remember during that time I was once talking to George when my friend and colleague the econometrician Tom Rothenberg came over and asked me to describe in one sentence what I had learned so far from the Akerlof-Kahneman course. I said, somewhat flippantly: “Kahneman is telling us that people are dumber than we economists think, and George is telling us that people are nicer than we economists think”. George liked this description so much that in the next class he started the lecture with my remark. On the dumbness of people I later read somewhere that Kahneman’s earlier fellow-Israeli co-author Amos Tversky once said when asked what he was working on, “My colleagues, they study artificial intelligence; me, I study natural stupidity.” Imagine someone told you that politics is a “great game,” that when citizens respect just principles, they do so “in much the same way that players have the shared end to execute a good and fair play of the game.” You would probably wonder if they meant it, if they really believed that civic duties resemble those acquired when “we join a game, namely, the obligations to play by the rules and to be a good sport.” You would because, for most people, politics is a serious business.

Imagine someone told you that politics is a “great game,” that when citizens respect just principles, they do so “in much the same way that players have the shared end to execute a good and fair play of the game.” You would probably wonder if they meant it, if they really believed that civic duties resemble those acquired when “we join a game, namely, the obligations to play by the rules and to be a good sport.” You would because, for most people, politics is a serious business. Isaac Newton was not known for his generosity of spirit, and his disdain for his rivals was legendary. But in one letter to his competitor Gottfried Leibniz, now known as the Epistola Posterior, Newton comes off as nostalgic and almost friendly. In it, he tells a story from his student days, when he was just beginning to learn mathematics. He recounts how he made a major discovery equating areas under curves with infinite sums by a process of guessing and checking. His reasoning in the letter is so charming and accessible, it reminds me of the pattern-guessing games little kids like to play.

Isaac Newton was not known for his generosity of spirit, and his disdain for his rivals was legendary. But in one letter to his competitor Gottfried Leibniz, now known as the Epistola Posterior, Newton comes off as nostalgic and almost friendly. In it, he tells a story from his student days, when he was just beginning to learn mathematics. He recounts how he made a major discovery equating areas under curves with infinite sums by a process of guessing and checking. His reasoning in the letter is so charming and accessible, it reminds me of the pattern-guessing games little kids like to play. AP: So, it’s not just the presence of English loanwords, but also how much of the original German novel is about who speaks in English and how that is a marker [of identity]. Nivedita grew up in Germany; her cousin Priti grew up in England. They meet because Priti comes to Germany to study the language for several summers in their youth. In the original, you see her command of German develop: she speaks a lot of English at first, and then, as the novel progresses, she’s speaking more and more German. Nivedita comments, “Wow, you know, Priti’s German was really getting good.” Basically, Priti is marked as the most “English” or British—the most not German character starting out. This couldn’t be replicated exactly in English, so I had to look for other little ways to solve it (like Priti mixing German into her speech in the English translation). That was one of the tricky things, and I never know how successfully I’ve solved a challenge. Beyond the character of Priti, I wanted to find ways to make it clear that Identitti originates in another language and then was brought into English. Some novels are inherently built that way because they’re constantly mentioning places or names. There are markers such that the reader never forgets that it’s happening where it’s happening. I didn’t want the North American reader to forget that the story they’re reading is taking place in Dusseldorf, Germany. But I also didn’t want to weigh the translation down with these unnecessary reminders. It was a fine line to walk.

AP: So, it’s not just the presence of English loanwords, but also how much of the original German novel is about who speaks in English and how that is a marker [of identity]. Nivedita grew up in Germany; her cousin Priti grew up in England. They meet because Priti comes to Germany to study the language for several summers in their youth. In the original, you see her command of German develop: she speaks a lot of English at first, and then, as the novel progresses, she’s speaking more and more German. Nivedita comments, “Wow, you know, Priti’s German was really getting good.” Basically, Priti is marked as the most “English” or British—the most not German character starting out. This couldn’t be replicated exactly in English, so I had to look for other little ways to solve it (like Priti mixing German into her speech in the English translation). That was one of the tricky things, and I never know how successfully I’ve solved a challenge. Beyond the character of Priti, I wanted to find ways to make it clear that Identitti originates in another language and then was brought into English. Some novels are inherently built that way because they’re constantly mentioning places or names. There are markers such that the reader never forgets that it’s happening where it’s happening. I didn’t want the North American reader to forget that the story they’re reading is taking place in Dusseldorf, Germany. But I also didn’t want to weigh the translation down with these unnecessary reminders. It was a fine line to walk. I

I In 2010, Brad St. Pierre and his wife, Christine, moved from California to Fairbanks, Alaska, to work as farmers. “People thought we were crazy,” Brad said. “They were, like, ‘You can grow things in Alaska?’ ” Their new home, not far from where Christine grew up, was as far north as Reykjavík, Iceland, and receives about sixty inches of snow each year. It routinely experiences winter temperatures below minus ten degrees Fahrenheit. In the summer, however, the sun shines for twenty-one hours a day and the weather resembles San Francisco’s. Sturdy cabbages and carrots thrive in the ground, while fussier tomatoes and cucumbers flourish in greenhouses.

In 2010, Brad St. Pierre and his wife, Christine, moved from California to Fairbanks, Alaska, to work as farmers. “People thought we were crazy,” Brad said. “They were, like, ‘You can grow things in Alaska?’ ” Their new home, not far from where Christine grew up, was as far north as Reykjavík, Iceland, and receives about sixty inches of snow each year. It routinely experiences winter temperatures below minus ten degrees Fahrenheit. In the summer, however, the sun shines for twenty-one hours a day and the weather resembles San Francisco’s. Sturdy cabbages and carrots thrive in the ground, while fussier tomatoes and cucumbers flourish in greenhouses. Pranab Bardhan in New Left Review:

Pranab Bardhan in New Left Review: Nell Minnow in response to 19 Republican state attorneys general’s letter to Blackrock:

Nell Minnow in response to 19 Republican state attorneys general’s letter to Blackrock: Dag Herbjørnsrud in Aeon:

Dag Herbjørnsrud in Aeon: I am 81 years old, my partner 92. On my 70th birthday, I woke from a dream in which I had rounded a corner and seen the end. This disturbing dream moved me to begin photographing the two of us, chronicling our time together, growing old.

I am 81 years old, my partner 92. On my 70th birthday, I woke from a dream in which I had rounded a corner and seen the end. This disturbing dream moved me to begin photographing the two of us, chronicling our time together, growing old.