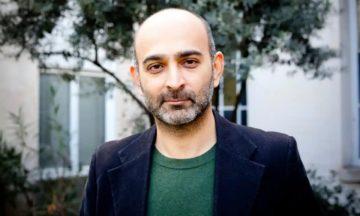

Mohsin Hamid in The Guardian:

In 2017, I published my fourth novel, Exit West, and bought a small notebook to jot down ideas for the next one. I thought it would be about technology. I came across an article by Simon DeDeo, an assistant professor at Carnegie Mellon University, discussing an experiment he and his colleague John Miller had conducted in that same year. They simulated cooperation and competition by machines over many generations, building these machines as computer models and setting them playing a game together. An interesting pattern emerged. Rather than constant trading for mutual benefit among equals, or never-ending fights to the death among foes, instead a particular type of machine became dominant, one that recognised and favoured copies of itself, and enormous prosperity ensued, built on ever-growing levels of cooperation. But eventually the minute differences that naturally occurred (or were, in the experiment, designed to occur) in the copying process, as they do in organisms when genes are passed on, became intolerable, and war among the machines resulted in near-complete devastation and a new beginning, after which the cycle repeated, over and over.

In 2017, I published my fourth novel, Exit West, and bought a small notebook to jot down ideas for the next one. I thought it would be about technology. I came across an article by Simon DeDeo, an assistant professor at Carnegie Mellon University, discussing an experiment he and his colleague John Miller had conducted in that same year. They simulated cooperation and competition by machines over many generations, building these machines as computer models and setting them playing a game together. An interesting pattern emerged. Rather than constant trading for mutual benefit among equals, or never-ending fights to the death among foes, instead a particular type of machine became dominant, one that recognised and favoured copies of itself, and enormous prosperity ensued, built on ever-growing levels of cooperation. But eventually the minute differences that naturally occurred (or were, in the experiment, designed to occur) in the copying process, as they do in organisms when genes are passed on, became intolerable, and war among the machines resulted in near-complete devastation and a new beginning, after which the cycle repeated, over and over.

More here.

The omicron variant did indeed become

The omicron variant did indeed become  On the fourth page of Pure Colour, the fourth and most recent novel by the Canadian writer Sheila Heti, it is proposed that there are three kinds of beings on the face of the earth. They are each a different kind of “critic,” tasked with helping God to improve upon His “first draft” of the universe. There are birds who “consider the world as if from a distance” and are interested in beauty above all. There are fish who “critique from the middle” and are consumed by the “condition of the many.” And there are bears who “do not have a pragmatic way of thinking” and are “deeply consumed with their own.” The three main characters in the novel track with the three types: Mira, the art critic and main character, is a bird; Mira’s father, whose death takes up the middle part of the novel, is a bear; and Mira’s romantic interest and colleague at a school for art critics, Annie, is a fish.

On the fourth page of Pure Colour, the fourth and most recent novel by the Canadian writer Sheila Heti, it is proposed that there are three kinds of beings on the face of the earth. They are each a different kind of “critic,” tasked with helping God to improve upon His “first draft” of the universe. There are birds who “consider the world as if from a distance” and are interested in beauty above all. There are fish who “critique from the middle” and are consumed by the “condition of the many.” And there are bears who “do not have a pragmatic way of thinking” and are “deeply consumed with their own.” The three main characters in the novel track with the three types: Mira, the art critic and main character, is a bird; Mira’s father, whose death takes up the middle part of the novel, is a bear; and Mira’s romantic interest and colleague at a school for art critics, Annie, is a fish. Americans aged sixty-two and older are the fastest-growing demographic of student borrowers. Of the forty-five million Americans who hold student debt, one in five are over fifty years old. Between 2004 and 2018, student-loan balances for borrowers over fifty increased by five hundred and twelve per cent. Perhaps because policymakers have considered student debt as the burden of upwardly mobile young people, inaction has seemed a reasonable response, as if time itself will solve the problem. But, in an era of declining wages and rising debt, Americans are not aging out of their student loans—they are aging into them.

Americans aged sixty-two and older are the fastest-growing demographic of student borrowers. Of the forty-five million Americans who hold student debt, one in five are over fifty years old. Between 2004 and 2018, student-loan balances for borrowers over fifty increased by five hundred and twelve per cent. Perhaps because policymakers have considered student debt as the burden of upwardly mobile young people, inaction has seemed a reasonable response, as if time itself will solve the problem. But, in an era of declining wages and rising debt, Americans are not aging out of their student loans—they are aging into them. Last May, after the Isla Vista shooter’s manifesto revealed a deep misogyny, women went online to talk about the violent retaliation of men they had rejected, to describe the feeling of being intimidated or harassed. These personal experiences soon took on a sense of universality. And so #yesallwomen was born—yes all women have been victims of male violence in one form or another. I was bothered by the hashtag campaign. Not by the male response, which ranged from outraged and cynical to condescending, nor the way the media dove in because the campaign was useful fodder. I recoiled from the gendering of pain, the installation of victimhood into the definition of femininity—and from the way pain became a polemic.

Last May, after the Isla Vista shooter’s manifesto revealed a deep misogyny, women went online to talk about the violent retaliation of men they had rejected, to describe the feeling of being intimidated or harassed. These personal experiences soon took on a sense of universality. And so #yesallwomen was born—yes all women have been victims of male violence in one form or another. I was bothered by the hashtag campaign. Not by the male response, which ranged from outraged and cynical to condescending, nor the way the media dove in because the campaign was useful fodder. I recoiled from the gendering of pain, the installation of victimhood into the definition of femininity—and from the way pain became a polemic. W

W Gregory Afinogenov in The Nation (illustration by Lily Qian):

Gregory Afinogenov in The Nation (illustration by Lily Qian): Patrick Iber interviews Matt Duss in Dissent:

Patrick Iber interviews Matt Duss in Dissent: N

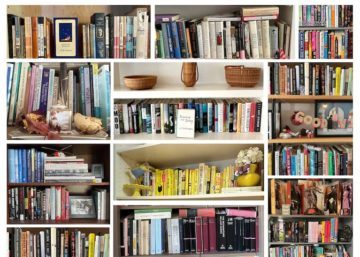

N My bookshelves are a mess. It’s not just that I have too many books and too little space. I’m also simply disorganized. It wasn’t always so. Shelves I put together years ago, pre-children, remain generally intact: a full bookcase of poetry, alphabetized by author, and several jam-packed bookcases of fiction, also by authors’ last names. These shelves now serve primarily as decoration or reference or as a lending library for guests. But there’s more, much more: the tumbling pile on my desk — propping up the computer I am typing on — and the volumes stuffed frantically in the bookcase in my bedroom and stacked in towers on and around my nightstand. These are the books that are part of my daily life — for work, for pleasure, sometimes both. There is no rhyme or reason to how I arrange them, but as I read in

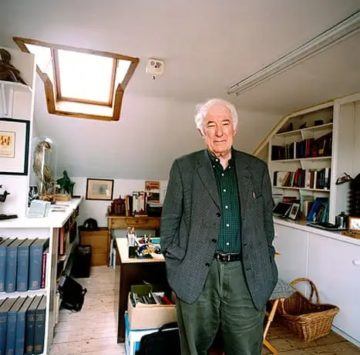

My bookshelves are a mess. It’s not just that I have too many books and too little space. I’m also simply disorganized. It wasn’t always so. Shelves I put together years ago, pre-children, remain generally intact: a full bookcase of poetry, alphabetized by author, and several jam-packed bookcases of fiction, also by authors’ last names. These shelves now serve primarily as decoration or reference or as a lending library for guests. But there’s more, much more: the tumbling pile on my desk — propping up the computer I am typing on — and the volumes stuffed frantically in the bookcase in my bedroom and stacked in towers on and around my nightstand. These are the books that are part of my daily life — for work, for pleasure, sometimes both. There is no rhyme or reason to how I arrange them, but as I read in  In the summer of 2012 Seamus Heaney wrote to me on some questions I had sent him about dictionaries and words and etymologies. Bits of what he had to say made it into a couple of talks I did around that time, but I recently rediscovered the original text, and thought it should see the light of day. So here’s a very lightly edited rendition of our exchange:

In the summer of 2012 Seamus Heaney wrote to me on some questions I had sent him about dictionaries and words and etymologies. Bits of what he had to say made it into a couple of talks I did around that time, but I recently rediscovered the original text, and thought it should see the light of day. So here’s a very lightly edited rendition of our exchange:

In a recent

In a recent