Michael L. Wilson and Richard W. Wrangham in Monkey Business:

In a recent opinion piece for Scientific American, John Horgan writes “Ending war won’t be easy, but it should be a moral imperative, as much so as ending slavery and the subjugation of women. The first step toward ending war is believing it is possible.” As part of his argument he declared that “far from having deep evolutionary roots, [war] is a relatively recent cultural invention.” We cherish the goal of ending war, but regard the claim of war being independent of our evolutionary past as unjustified, irresponsible and improbable. It is possibly based on a misunderstanding of what it means for a behavior to have evolutionary roots, but regardless of its derivation, we see it as dangerous. The problem is that if Horgan’s view prevails, we close our minds to potentially important contributions towards understanding the causes of wars.

More here.

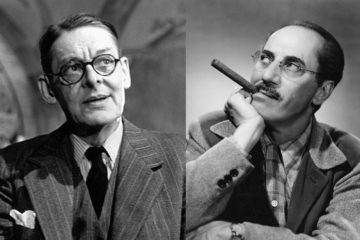

In 1961 a letter with a Royal Mail postmark arrived at 1083 North Hillcrest Road, Beverly Hills. Fan mail sent to this modernist estate amidst the California scrub were not uncommon. After all, it was the home of Julius “Groucho” Marx, the visionary leader of the fraternal comedic group. This particular note had a return address of 3 Kensington Court Gardens, a continent and an ocean away.

In 1961 a letter with a Royal Mail postmark arrived at 1083 North Hillcrest Road, Beverly Hills. Fan mail sent to this modernist estate amidst the California scrub were not uncommon. After all, it was the home of Julius “Groucho” Marx, the visionary leader of the fraternal comedic group. This particular note had a return address of 3 Kensington Court Gardens, a continent and an ocean away. S

S Andrew Yamakawa Elrod in Phenomenal World:

Andrew Yamakawa Elrod in Phenomenal World: I’m not at the Cannes Film Festival, but a few days ago the festival came to me, at a New York screening of a movie that premièred today at Cannes. The film is

I’m not at the Cannes Film Festival, but a few days ago the festival came to me, at a New York screening of a movie that premièred today at Cannes. The film is  Last fall, I made my first visit to London since the start of the pandemic. A routine commuter flight from Europe felt like a great adventure, and once I’d jumped through the bureaucratic hoops, I was excited to arrive. But the city looked disappointingly unchanged after everything the world had gone through. The only thing that really shocked me was something I hadn’t expected: hearing people speaking English. After two years away from it, I had never felt so moved to encounter my own language.

Last fall, I made my first visit to London since the start of the pandemic. A routine commuter flight from Europe felt like a great adventure, and once I’d jumped through the bureaucratic hoops, I was excited to arrive. But the city looked disappointingly unchanged after everything the world had gone through. The only thing that really shocked me was something I hadn’t expected: hearing people speaking English. After two years away from it, I had never felt so moved to encounter my own language. It was if he’d stepped, steaming, out of a Tom of Finland drawing. “My definition of tit for tat,” he wrote, is: “You lick my tattoo while I handle your nipple.”

It was if he’d stepped, steaming, out of a Tom of Finland drawing. “My definition of tit for tat,” he wrote, is: “You lick my tattoo while I handle your nipple.” A

A  From the Dynomight blog:

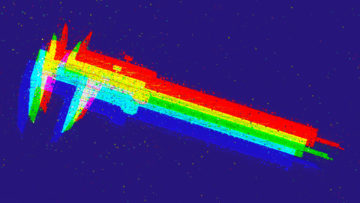

From the Dynomight blog:  Scientific progress has been inseparable from better measurements.

Scientific progress has been inseparable from better measurements. The idea that committing atrocities and killing innocent victims reflects mental illness has been

The idea that committing atrocities and killing innocent victims reflects mental illness has been  After his grandfather suffered a spinal cord injury in a car accident, Chris Dulla wondered how his wounded brain cells would repair themselves. So when Dulla learned in medical school two decades ago that star-shaped brain cells called astrocytes support neurons and play a vital role in injury response and recovery, he felt the urge to dive deeper into the topic.

After his grandfather suffered a spinal cord injury in a car accident, Chris Dulla wondered how his wounded brain cells would repair themselves. So when Dulla learned in medical school two decades ago that star-shaped brain cells called astrocytes support neurons and play a vital role in injury response and recovery, he felt the urge to dive deeper into the topic.