Adam Kirsch in The New Yorker:

The Western tradition has never been more appealingly portrayed than in Rembrandt’s 1653 painting “Aristotle with a Bust of Homer.” Whether you stand in front of it at the Metropolitan Museum or look at it online, the painting turns you into a link in a chain that goes back three thousand years. Here you are in the twenty-first century, contemplating a painting made in Amsterdam in the seventeenth century, which portrays a philosopher who lived in Athens in the fourth century B.C., looking at a poet thought to have lived in the eighth century B.C. Tradition abolishes time, making us all contemporaries. Yet the painting hints that Homer doesn’t quite belong in the same dimension of reality occupied by you, Aristotle, and Rembrandt.

The Western tradition has never been more appealingly portrayed than in Rembrandt’s 1653 painting “Aristotle with a Bust of Homer.” Whether you stand in front of it at the Metropolitan Museum or look at it online, the painting turns you into a link in a chain that goes back three thousand years. Here you are in the twenty-first century, contemplating a painting made in Amsterdam in the seventeenth century, which portrays a philosopher who lived in Athens in the fourth century B.C., looking at a poet thought to have lived in the eighth century B.C. Tradition abolishes time, making us all contemporaries. Yet the painting hints that Homer doesn’t quite belong in the same dimension of reality occupied by you, Aristotle, and Rembrandt.

Aristotle is portrayed realistically in the dress of Rembrandt’s time—sumptuous white shirt, simple black apron, and broad-brimmed hat. (It wasn’t until the twentieth century that art historians determined that the figure was Aristotle; earlier identifications included a contemporary of Rembrandt’s, the writer Pieter Cornelisz Hooft.) In other words, Aristotle is a human being like us, albeit an extraordinary one. Homer, however, is a white marble bust—a work of art within a work of art.

It’s a reminder that, even for Aristotle, Homer was more a legend than a man. In his Poetics, the philosopher credits the poet with inventing epic, drama, and comedy. “It is Homer who has chiefly taught other poets the art of telling lies skillfully,” he writes with evident ambivalence. Herodotus, known as the first historian, saw Homer, along with the poet Hesiod, as having invented Greek mythology, calling them the first to “give the gods their epithets, to allot them their several offices and occupations, and describe their forms.” When it comes to things like when and where Homer lived, however, the earliest sources are already unreliable. According to tradition, the poet was blind and was born on the island of Chios, where a guild of rhapsodes—reciters of epic poetry—later became known as the Homeridae, “children of Homer,” and claimed to be his direct descendants. But there is no evidence for any of these assertions, and some ancient biographies of Homer are obviously fanciful.

Herodotus writes that Homer lived “four hundred years before my time,” which would put him in the ninth century B.C., but adds that this is “my own opinion,” with no real proof behind it.

More here.

When challenged, former President Donald Trump often claimed he was the victim of a witch hunt, even “the greatest Witch Hunt in American history.” This was not just an exaggeration but an inversion: He was being investigated in search of truth, while in a witch hunt, a forgone guilty verdict is reached by twisted interpretation and fantastical invention.

When challenged, former President Donald Trump often claimed he was the victim of a witch hunt, even “the greatest Witch Hunt in American history.” This was not just an exaggeration but an inversion: He was being investigated in search of truth, while in a witch hunt, a forgone guilty verdict is reached by twisted interpretation and fantastical invention.

Nero, who was enthroned in Rome in 54 A.D., at the age of sixteen, and went on to rule for nearly a decade and a half, developed a reputation for tyranny, murderous cruelty, and decadence that has survived for nearly two thousand years. According to various Roman historians, he commissioned the assassination of Agrippina the Younger—his mother and sometime lover. He sought to poison her, then to have her crushed by a falling ceiling or drowned in a self-sinking boat, before ultimately having her murder disguised as a suicide. Nero was betrothed at eleven and married at fifteen, to his adoptive stepsister, Claudia Octavia, the daughter of the emperor Claudius. At the age of twenty-four, Nero divorced her, banished her, ordered her bound with her wrists slit, and had her suffocated in a steam bath. He received her decapitated head when it was delivered to his court. He also murdered his second wife, the noblewoman Poppaea Sabina, by kicking her in the belly while she was pregnant.

Nero, who was enthroned in Rome in 54 A.D., at the age of sixteen, and went on to rule for nearly a decade and a half, developed a reputation for tyranny, murderous cruelty, and decadence that has survived for nearly two thousand years. According to various Roman historians, he commissioned the assassination of Agrippina the Younger—his mother and sometime lover. He sought to poison her, then to have her crushed by a falling ceiling or drowned in a self-sinking boat, before ultimately having her murder disguised as a suicide. Nero was betrothed at eleven and married at fifteen, to his adoptive stepsister, Claudia Octavia, the daughter of the emperor Claudius. At the age of twenty-four, Nero divorced her, banished her, ordered her bound with her wrists slit, and had her suffocated in a steam bath. He received her decapitated head when it was delivered to his court. He also murdered his second wife, the noblewoman Poppaea Sabina, by kicking her in the belly while she was pregnant. To become prime minister, Mr. Modi overcame a reputation tarnished by his alleged involvement in

To become prime minister, Mr. Modi overcame a reputation tarnished by his alleged involvement in  Mona Ali in Phenomenal World:

Mona Ali in Phenomenal World: Leo Robson in the NLR’s Sidecar:

Leo Robson in the NLR’s Sidecar: Steven Pinker: The idea behind effective altruism is to channel charitable giving and other philanthropic activities to where they will do the most good, where they would lead to the greatest increase in human flourishing. And the reason that it’s needed is that we are all altruistic. It is part of human nature. On the other hand, we have a large set of motives for why we’re altruistic and some of them are ulterior — such as appearing beneficent and generous, or earning friends and cooperation partners. Some of them may result in conspicuous sacrifices that indicate that we are generous and trustworthy people to our peers but don’t necessarily do anyone any good. And so the idea behind effective altruism is to determine where your activities actually save lives, increase health, reduce poverty, and at the very least provide people opportunities to channel their philanthropy where it will do the most good. And, of course, also to encourage people to do that. So part of it is just informing people if that is their goal and telling them that these are the ways to do it. And the other is to spread the value that that’s where philanthropy ought to be directed.

Steven Pinker: The idea behind effective altruism is to channel charitable giving and other philanthropic activities to where they will do the most good, where they would lead to the greatest increase in human flourishing. And the reason that it’s needed is that we are all altruistic. It is part of human nature. On the other hand, we have a large set of motives for why we’re altruistic and some of them are ulterior — such as appearing beneficent and generous, or earning friends and cooperation partners. Some of them may result in conspicuous sacrifices that indicate that we are generous and trustworthy people to our peers but don’t necessarily do anyone any good. And so the idea behind effective altruism is to determine where your activities actually save lives, increase health, reduce poverty, and at the very least provide people opportunities to channel their philanthropy where it will do the most good. And, of course, also to encourage people to do that. So part of it is just informing people if that is their goal and telling them that these are the ways to do it. And the other is to spread the value that that’s where philanthropy ought to be directed. ROSENBAUM:

ROSENBAUM:  In the early 90s, governments started buying into an argument about capital mobility, taxes and welfare states: in a world of global capital, investors will seek the best returns they can get globally. If those returns are reduced by “distortions” such as taxes, investment will flow to countries that tax less. Consequently, those expensive and expansive welfare states that neoliberal economists had always targeted had to go. Funding them through taxing the wealthy and corporations would lower investment and employment, so the story went.

In the early 90s, governments started buying into an argument about capital mobility, taxes and welfare states: in a world of global capital, investors will seek the best returns they can get globally. If those returns are reduced by “distortions” such as taxes, investment will flow to countries that tax less. Consequently, those expensive and expansive welfare states that neoliberal economists had always targeted had to go. Funding them through taxing the wealthy and corporations would lower investment and employment, so the story went. Tyree’s answer to our present dilemma is weirdness, “cultivated eccentricity as an antidote to a world gone mad.” He proposes a Pynchonian counterforce, a ragged band of outsiders and misfits to resist all the orthodoxies of the day. Despite the polarization of the moment, both the left and the right feverishly engage in what Tyree terms timewashing: “[O]ur era’s signature creation of fake pasts that purport to cleanse history of its deep stains and recurring nightmares with the scented spray of propaganda.” Our “incapacity to live with the past in all its troubling complexity” poses a grave danger, he argues, and better fiction could be our salvation. He’s right, of course, but he also knows the unlikelihood of his solution: “Is it naïve to assert that we badly need dreamers like Pynchon to help us imagine a different future by reading through a different lens on our past?” Tyree answers his own question just three sentences later: “Yeah, that’s probably naïve.”

Tyree’s answer to our present dilemma is weirdness, “cultivated eccentricity as an antidote to a world gone mad.” He proposes a Pynchonian counterforce, a ragged band of outsiders and misfits to resist all the orthodoxies of the day. Despite the polarization of the moment, both the left and the right feverishly engage in what Tyree terms timewashing: “[O]ur era’s signature creation of fake pasts that purport to cleanse history of its deep stains and recurring nightmares with the scented spray of propaganda.” Our “incapacity to live with the past in all its troubling complexity” poses a grave danger, he argues, and better fiction could be our salvation. He’s right, of course, but he also knows the unlikelihood of his solution: “Is it naïve to assert that we badly need dreamers like Pynchon to help us imagine a different future by reading through a different lens on our past?” Tyree answers his own question just three sentences later: “Yeah, that’s probably naïve.” The Western tradition has never been more appealingly portrayed than in

The Western tradition has never been more appealingly portrayed than in  It’s often cancer’s spread, not the original tumor, that poses the disease’s most deadly risk. “And yet metastasis is one of the most poorly understood aspects of

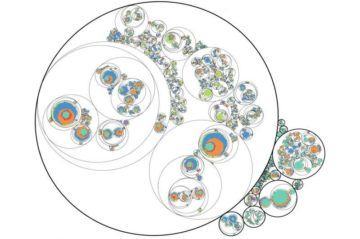

It’s often cancer’s spread, not the original tumor, that poses the disease’s most deadly risk. “And yet metastasis is one of the most poorly understood aspects of

These squiggles have a meaning. So do spoken words, road signs, mathematical equations and signal flags. Meaning is something with which we’re intimately familiar – so familiar that, for the most part, we barely register or think about it at all. And yet, once we do begin to reflect on meaning, it can quickly begin to seem bizarre and even magical. How can a few marks on a sheet of paper reach out across time to refer to a person long dead? How can a mere sound in the air instantaneously pick out a galaxy light-years away? What gives words these extraordinary powers? The answer, of course, is that we do. But how?

These squiggles have a meaning. So do spoken words, road signs, mathematical equations and signal flags. Meaning is something with which we’re intimately familiar – so familiar that, for the most part, we barely register or think about it at all. And yet, once we do begin to reflect on meaning, it can quickly begin to seem bizarre and even magical. How can a few marks on a sheet of paper reach out across time to refer to a person long dead? How can a mere sound in the air instantaneously pick out a galaxy light-years away? What gives words these extraordinary powers? The answer, of course, is that we do. But how? While the dramatic breach of the Edenville Dam captured national headlines, an Undark investigation has identified 81 other dams in 24 states, that, if they were to fail, could flood a major toxic waste site and potentially spread contaminated material into surrounding communities.

While the dramatic breach of the Edenville Dam captured national headlines, an Undark investigation has identified 81 other dams in 24 states, that, if they were to fail, could flood a major toxic waste site and potentially spread contaminated material into surrounding communities.