Month: March 2021

Adam Zagajewski (1945 – 2021)

Bertrand Tavernier (1941 – 2021)

The Apocalyptic New Campus Novel

Charlie Tyson reviews Christine Smallwood’s The Life of the Mind in The Chronicle of Higher Education:

Charlie Tyson reviews Christine Smallwood’s The Life of the Mind in The Chronicle of Higher Education:

Early in graduate school, I had a curious dream. I had finished my dissertation, but no job was forthcoming. Taking pity on me, my department hired me to perform the functions of a janitor-cum-chambermaid. A pathetic scene followed. I found myself down on my hands and knees, scrubbing the floor tiles of the humanities building, choking on the fumes of cleaning fluid, squeezing my rag into a bucket of dirty suds. Students teemed past holding lattes. My former professors averted their eyes. “At least I can tell people I work at Harvard,” I thought madly, as hot tears spilled down and mingled with the lemon disinfectant.

I recalled this nightmare of bourgeois indignity while reading Christine Smallwood’s debut novel of academic precarity, The Life of the Mind (2021) — the book’s key theme is the production of waste, and the task of cleaning up afterward. Smallwood’s sendup of contemporary academic life follows Dorothy, an adjunct instructor in the English department of a private university in New York City. The novel opens with Dorothy on the toilet in the middle of a bowel movement. It ends with her dumping a sheaf of student essays, each marked with a desultory A-minus, one by one into the trash.

More here.

The new essentialism?

Simon Garnett in Eurozine:

If we share the assumption that every culture is necessarily incomplete in itself and that there is no such thing as a self-contained, homogeneous culture, then the very definition of a given culture has to include what I would call inter-translatability. In other words, being-in-translation is an essential defining feature of the concept of culture itself.

This passage is taken from an essay by António Sousa Ribeiro published in Eurozine in 2004. Entitled The reason of borders or a border reason?, the piece argues for a ‘relational’ understanding of identity and for ‘translation’ – both in a literal and a figurative sense – as a form of ‘counter-hegemonic globalization’.

I was put in mind of this piece – which itself has been translated into six languages – by the recent debate over the appropriateness of a white person translating the work of a black poet.

The debate has certainly been positive in one respect: namely, in drawing attention to the ‘whiteness’ of the literary translation business and the literary sector generally. While an increasing number of non-white authors are being published, editorial departments in particular lack diversity. As a symbolic gesture, to insist that Amanda Gorman be translated by a black translator made sense.

But, for reasons that may have nothing to do with the original intervention, the debate has also become about something more fundamental: whether the translator’s whiteness renders them incapable of doing justice to the black poet’s work.

More here.

Precarity and Struggle: Kafka, Roth, Kraus

Ari Linden in Public Books:

Ari Linden in Public Books:

We know that things in our world have gone awry when Franz Kafka resonates: “The world will offer itself to you to be unmasked, it cannot do otherwise, it will writhe in front of you in ecstasies.” As we all anxiously await a less metaphysical unmasking, such a sentiment speaks to a current mood of tenuous anticipation, as it likely would have in the early 20th century had the text in which it appears been published along with Kafka’s more famous works. Instead, it is included now in a slim volume titled The Lost Writings, composed primarily of short stories and fragments that have been “lost to sight for decades.” Curated by the Kafka scholar and preeminent biographer Reiner Stach and sifted from the Nachgelassene Schriften und Fragmente, these texts have been newly translated into English by Michael Hofmann, two of them for the first time. To give a sense of Hofmann’s literary instincts: “exposed” or “disclosed” would have worked for “Entlarvung” in the aphorism above, but “unmasking” was clearly the right choice.

Scholars have frequently alighted on notions of negativity or absence as the paradoxically defining feature of Kafka’s work. Most recently, Paul Buchholz has written on Kafka’s literary “self-nullification,” which nonetheless contains a quasi-redemptive moment: “a lonely protagonist may erase the world around him, fall into an abyss that he has created for himself, and finally find there the conditions for affirmative community.”

More here.

Parul Sehgal Talks With Erica Jong

A Meditation On Quantum Theory

Manjit Kumar at The Guardian:

With the light touch of a skilled storyteller, Rovelli reveals that Heisenberg had been wrestling with the inner workings of the quantum atom in which electrons travel around the nucleus only in certain orbits, at certain distances, with certain precise energies before magically “leaping” from one orbit to another. Among the unsolved questions he was grappling with on Helgoland were: why only these orbits? Why only certain orbital leaps? As he tried to overcome the failure of existing formulas to replicate the intensity of the light emitted as an electron leapt between orbits, Heisenberg made an astonishing leap of his own. He decided to focus only on those quantities that are observable – the light an atom emits when an electron jumps. It was a strange idea but one that, as Rovelli points out, made it possible to account for all the recalcitrant facts and to develop a mathematically coherent theory of the atomic world.

With the light touch of a skilled storyteller, Rovelli reveals that Heisenberg had been wrestling with the inner workings of the quantum atom in which electrons travel around the nucleus only in certain orbits, at certain distances, with certain precise energies before magically “leaping” from one orbit to another. Among the unsolved questions he was grappling with on Helgoland were: why only these orbits? Why only certain orbital leaps? As he tried to overcome the failure of existing formulas to replicate the intensity of the light emitted as an electron leapt between orbits, Heisenberg made an astonishing leap of his own. He decided to focus only on those quantities that are observable – the light an atom emits when an electron jumps. It was a strange idea but one that, as Rovelli points out, made it possible to account for all the recalcitrant facts and to develop a mathematically coherent theory of the atomic world.

more here.

New ‘Revelations’ in the Life of Francis Bacon

Parul Sehgal at the NYT:

“A deep-end girl,” he called himself, not one “minnying along the sidewalk of life.”

“A deep-end girl,” he called himself, not one “minnying along the sidewalk of life.”

In their new book, “Francis Bacon: Revelations,” Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan, awarded the Pulitzer Prize for their 2004 biography of Willem de Kooning, argue that Bacon discouraged investigations into his life because he still harbored “one big secret.”

I sat up in my chair, too. What remains to be known? “Bacon was exhibitionistically frank about the traumatic adolescent events that would define his role as an artist as well as a lover,” according to Richardson. There exists a shelf of excellent, gossipy accounts of his life, many by his friends, full of Bacon’s stories about his childhood, its isolation and grim thrills.

Automation and the Future of Work

Saturday Poem

A Game of Glass

I do not believe this room

with its cat and its chandelier,

its chessboard-tiled floor,

and its shutter that opens out

on an angel playing a fountain,

and the striped light slivering in

to a room that looks the same

in the mirror over my shoulder,

with a second glass-eyed cat.

My book does not look real,

The room and the mirror seem

to be playing a waiting game.

The cat has made its move,

the fountain has one to play,

and the thousand eyes of the angel

in the chandelier above

gleam beadily, and say

the next move is up to me.

How can I trust my luck?

Whatever way I look,

I cannot tell which is the door,

and I do not know who is who—

the thin man in the mirror,

or the watery one in the fountain.

The cat is eying my book.

What am I meant to do?

Which side is the mirror on?

by Alastair Reid

from Poets Choice

Time/Life Books, 1962

Severe illness refigures you – it’s like passing through a fire

Lisa Allardice in The Guardian:

Maggie O’Farrell found the prospect of writing the central scenes of her prize-winning novel Hamnet, in which a mother sits helplessly by the bedside of her dying son, so traumatic that she couldn’t write them in the house. Instead, she had to escape to the shed, and “not a smart writing shed like Philip Pullman’s”, she says, “but a really disgusting, spidery, manky potting shed, which has since blown down in a gale”. And she could only do it in short bursts of 15 or 20 minutes before she would have to take a walk around the garden, and then go back in again.

Maggie O’Farrell found the prospect of writing the central scenes of her prize-winning novel Hamnet, in which a mother sits helplessly by the bedside of her dying son, so traumatic that she couldn’t write them in the house. Instead, she had to escape to the shed, and “not a smart writing shed like Philip Pullman’s”, she says, “but a really disgusting, spidery, manky potting shed, which has since blown down in a gale”. And she could only do it in short bursts of 15 or 20 minutes before she would have to take a walk around the garden, and then go back in again.

The novel, a fictionalised account of the death of Shakespeare’s only son from the bubonic plague (his twin sister Judith survived) and an at times almost unbearably tender portrayal of grief, was first published a year ago. An interlude halfway through, which follows the journey of the plague in 1595 from a flea on a monkey in Alexandria to a cabin boy back to London and eventually to Stratford, was referred to by an American journalist as “the contact tracing chapter”. “It certainly wasn’t conceived as that when I wrote it,” the author says of the extraordinary coincidence of her novel, set more than 400 years ago, landing in the middle of the pandemic, not least because she delayed writing it for decades.

More here.

Suleika Jaouad Does Not Want to Be Your Mountaintop Sage

Elisabeth Egan in The New York Times:

ROAD WARRIOR In the month since the publication of her memoir, “Between Two Kingdoms,” which just spent three weeks on the hardcover nonfiction list, Suleika Jaoaud has heard from a number of individuals she didn’t expect to be in touch with — including her fourth grade teacher; a California oncologist who was a fellow at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City when Jaoaud was diagnosed with leukemia at the age of 22; and a lawyer offering counsel to a Texas prisoner Jaouad writes about in the book. These readers have been moved by Jaouad’s story of surviving cancer and then taking a 15,000-mile road trip to visit people — many of them strangers — who responded to the New York Times blog where she chronicled her experience as a young adult facing her own mortality. By now, we all know it takes a village (albeit a socially distanced one) to endure illness, isolation and fear. “Between Two Kingdoms” drives home the fact that, where cancer is concerned, it takes an empire.

ROAD WARRIOR In the month since the publication of her memoir, “Between Two Kingdoms,” which just spent three weeks on the hardcover nonfiction list, Suleika Jaoaud has heard from a number of individuals she didn’t expect to be in touch with — including her fourth grade teacher; a California oncologist who was a fellow at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City when Jaoaud was diagnosed with leukemia at the age of 22; and a lawyer offering counsel to a Texas prisoner Jaouad writes about in the book. These readers have been moved by Jaouad’s story of surviving cancer and then taking a 15,000-mile road trip to visit people — many of them strangers — who responded to the New York Times blog where she chronicled her experience as a young adult facing her own mortality. By now, we all know it takes a village (albeit a socially distanced one) to endure illness, isolation and fear. “Between Two Kingdoms” drives home the fact that, where cancer is concerned, it takes an empire.

The idea for the road trip and the memoir arrived when Jaouad found herself at a crossroads. “I felt like I should be living some version of the heroic journey I’d been bombarded with,” she said in a phone interview. “But I didn’t feel excited; I didn’t feel done. There was this strange omertà of silence that seemed to enshroud survivorship. I’m always interested in traveling to where the silence is, so once I detected it, I knew that would be something that I wanted to interrogate.”

Jaoaud’s nearest and dearest understood that there was no talking her out of her journey once her mind was made up, although some worried about her safety since she’d only had her driver’s license for a month. She recalled visiting her parents in Saratoga Springs, N.Y., about a week into the expedition: “My dad explained to me how, if you lean forward and look in the mirror, you can notice your blind spots.”

More here. (Note: One of the best books I read this year!)

The Debt We Owe Edward Said

Kaleem Hawa in The Nation:

Edward Said was our prince,” the Egyptian novelist Ahdaf Soueif recently said in a conversation reflecting on the Palestinian public intellectual’s life and writings. An incomparable thinker, Said is credited with founding postcolonial studies, penning histories of cultural representation and “the Other,” and, in so doing, upending the Anglo-American academy. His Orientalism, published in 1978, is among the most cited books in modern history, by some accounts above Marx’s Capital and Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. Throughout decades of essays, books, and reviews, Said showed his care for form and the structures of feeling, seeing in their examination a means of understanding music, literature, the world, and Palestine, his home.

Edward Said was our prince,” the Egyptian novelist Ahdaf Soueif recently said in a conversation reflecting on the Palestinian public intellectual’s life and writings. An incomparable thinker, Said is credited with founding postcolonial studies, penning histories of cultural representation and “the Other,” and, in so doing, upending the Anglo-American academy. His Orientalism, published in 1978, is among the most cited books in modern history, by some accounts above Marx’s Capital and Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. Throughout decades of essays, books, and reviews, Said showed his care for form and the structures of feeling, seeing in their examination a means of understanding music, literature, the world, and Palestine, his home.

Said was many other things—a critic, a dandy, a narcissist, a mentor, a polemicist, and a singular wit. In 1995’s Peace and Its Discontents—the first of his books intended for an Arab audience—Said describes the Oslo Accords as a “degrading spectacle of Yasser Arafat thanking everyone for what amounted to a suspension of his people’s rights,” shrouded in the “fatuous solemnity of Bill Clinton’s performance, like a twentieth century Roman empire shepherding two vassal knights through rituals of reconciliation and obeisance.” The Palestinian leader for decades, Arafat would come to ban Said’s books in the West Bank and Gaza, a result of Said’s early positions in support of the one-state solution and his criticisms of Oslo.

Said’s commitment to the liberation of the Palestinian people made him enemies closer to home as well.

More here.

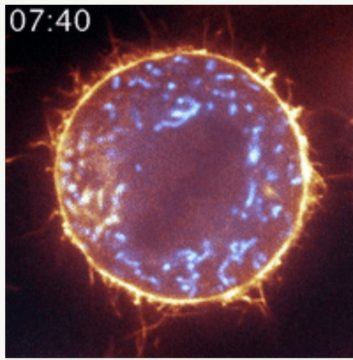

Researchers Reveal How a Cell Mixes its Mitochondria Before It Divides

From Penn Medicine News:

In a landmark study, a team led by researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania has discovered—and filmed—the molecular details of how a cell, just before it divides in two, shuffles important internal components called mitochondria to distribute them evenly to its two daughter cells.

In a landmark study, a team led by researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania has discovered—and filmed—the molecular details of how a cell, just before it divides in two, shuffles important internal components called mitochondria to distribute them evenly to its two daughter cells.

The finding, published in Nature, is principally a feat of basic cell biology, but this line of research may one day help scientists understand a host of mitochondrial and cell division-related diseases, from cancer to Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

Mitochondria are tiny oxygen reactors that are crucial for energy production in cells. The Penn Medicine team found in the study that a protein called actin, which is known to assemble into filaments that play a variety of structural roles in cells, also has the important task of ensuring an even distribution of mitochondria prior to cell division. Thanks to this system, the two new cells formed by the division will end up with approximately the same mass and quality of these critical energy producers.

More here.

A rare clip of Einstein speaking about relativity

Cynthia Haven: My never-before-published Q&A with Adam Zagajewski

Cynthia Haven in her blog:

I wrote about poet Adam Zagajewski, who died last weekend at 75, for the Poetry Foundation about a decade ago. The published article, “Risk, Try, Revise, Erase,” wasn’t a Q&A, but I sent him some questions anyway, for the fun of it. Some of his replies were included in my article, but my questions were more guided by my interests and curiosity than focused journalistic intent.

I wrote about poet Adam Zagajewski, who died last weekend at 75, for the Poetry Foundation about a decade ago. The published article, “Risk, Try, Revise, Erase,” wasn’t a Q&A, but I sent him some questions anyway, for the fun of it. Some of his replies were included in my article, but my questions were more guided by my interests and curiosity than focused journalistic intent.

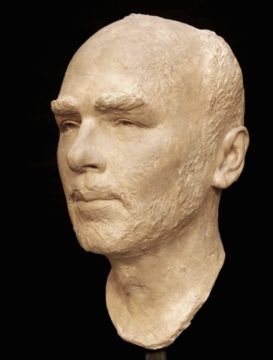

That’s why this interview was never published before. It didn’t seem polished enough or grand enough. But I can’t get my friend out of my mind today. So the Book Haven provides me an opportunity to share these outtakes with a very gifted poet who left us too soon. He was one of the reasons I wanted to go back to Kraków, and now it’s hard to imagine the city without him. It is said that he lived in the shadow of poetry giants, but he also became one, and on his own his quiet terms. (A week or ago I wrote about sculptor Jonathan Hirschfeld’s sculpture of Miłosz. I also share his portrait of Adam above, circa 1990, in the same spirit of the moment.)

Q. First, a simple question from my own personal interest. I love your poem “Three Angels.” It takes place on St. George Street – I take it that’s in Kraków? Did you have any particular bakery in mind when you wrote this poem?

A. No, there’s no bakery in the St. George Street. Actually there’s no St. George Street in Krakow–there’s a St. John Street, though. I like sometimes small shifts like that: I’m close to reality but not too close. And there are many bakers in Krakow (bread is good here).

More here.

The Sexual Translator

Wayne Koestenbaum at n+1:

The pivotal event in our friendship concerned Mallarmé. The translator, Abel Mars, had discovered the secret key to Divagations, and embarked on a translation that would reveal to the world the unsuspected sexual architecture underlying Mallarmé’s sense-confounding essays, which destroyed readers while seeming to titillate them. Abel (or Abelline, as I sometimes called him, in moments of intimacy) had a fear of blue objects (vases, shirts, flowers, paintings, rugs); anything blue horrified him, perhaps because his mother had once exposed him, during a childhood attack of meningitis, to a not-yet-patented blue light, which a quack acquaintance had pushed on the family as a cure-all device for their ailing, precocious son. The blue light, which his mother had trained on his naked body as he lay on the living room carpet, had caused him to bleed from the ears; the bleeding cured his meningitis—expelling it from his body—but instilled in him a fear of anything blue. More logical it would have been if Abel had grown to fear illness itself; paradoxically, he feared not the pathogens but the anti-pathogens.

more here.

Do We Know What Knowing Is?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=15-PCBFutos

Magic, Mystery, and Imagination in American Realism

Albert Mobilio at Artforum:

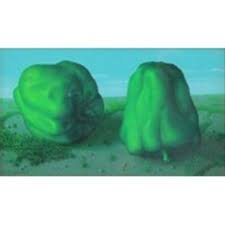

Charles Patterson’s Peppers, 1953, presents a pair of gigantic green peppers against an unnaturally manicured landscape. Textured with a kind of tense muscularity, the fruits convey the sense they might burst forth from the board and, as such, are more than a little bit threatening. This slightly off-kilter depiction of quotidian objects, rendered with painterly exactitude, seems precisely to fit Barr’s characterization. But in another piece of Patterson’s—The Room, 1958—the stagey improbability and expressionless faces of its five assembled characters combine to much less disconcerting effect. A wide-eyed female figure reclines on a divan while a man and woman struggle with a large dog that may wish to chase the cat dashing beneath the studio couch. An open curtain behind the group reveals an elderly woman robing a skeletal figure in a bath. If the realm of unconscious reverie is being evoked, it is done with a deliberateness that recalls the clichés of an overly earnest Surrealism—locomotives emerging from fireplaces, elephants on bony stilts, and the like.

Charles Patterson’s Peppers, 1953, presents a pair of gigantic green peppers against an unnaturally manicured landscape. Textured with a kind of tense muscularity, the fruits convey the sense they might burst forth from the board and, as such, are more than a little bit threatening. This slightly off-kilter depiction of quotidian objects, rendered with painterly exactitude, seems precisely to fit Barr’s characterization. But in another piece of Patterson’s—The Room, 1958—the stagey improbability and expressionless faces of its five assembled characters combine to much less disconcerting effect. A wide-eyed female figure reclines on a divan while a man and woman struggle with a large dog that may wish to chase the cat dashing beneath the studio couch. An open curtain behind the group reveals an elderly woman robing a skeletal figure in a bath. If the realm of unconscious reverie is being evoked, it is done with a deliberateness that recalls the clichés of an overly earnest Surrealism—locomotives emerging from fireplaces, elephants on bony stilts, and the like.

more here.