From Delancy Place:

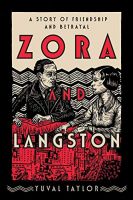

Today’s selection — from Zora and Langston by Yuval Taylor. Zora Neale Hurston started out her career as an anthropologist recording black folklore with the encouragement of Franz Boas, but her real passion was hybrid — a genre that fused fiction and folk, which symbolized “every aspect of daily life”:

Today’s selection — from Zora and Langston by Yuval Taylor. Zora Neale Hurston started out her career as an anthropologist recording black folklore with the encouragement of Franz Boas, but her real passion was hybrid — a genre that fused fiction and folk, which symbolized “every aspect of daily life”:

“Zora had begun studying anthropology under Franz Boas at Columbia in the fall of 1925, which involved a momentous shift of perspective. All her life Zora had been immersed in black folkways and had never even thought of separating her identity from those of the folk. She used to tell this story: when a policeman stopped her from crossing on a red light, she told him that since she saw all the white people crossing on green, she thought the red light was for colored folks. Here, as she often did, she was taking a common black folktale and applying it to herself. Zora defined folklore as ‘the arts of the people before they find out that there is any such thing as art, and they make it out of whatever they find at hand’; as a corollary, the folklore that Zora had always drawn on was suddenly art to her: it had changed its nature.

“Therefore, now that she was embarking on a course of studying the folk, she could no longer be one of them. As she would write at the beginning of Mules and Men, ‘From the earliest rocking of my cradle, I had known about the capers Brer Rabbit is apt to cut and what the Squinch Owl says from the house top. But it was fitting me like a tight chemise. I couldn’t see it for wearing it. It was only when I was off in college, away from my native surroundings, that I could see myself like somebody else and stand off and look at my garment. Then I had to have the spy-glass of Anthropology to look through at that.’ Suddenly African American culture was a thing to research rather than to roll around in and play with.

“In this new endeavor she could not have asked for a better guide than Franz Boas, whom she idolized, calling him ‘the greatest anthropologist alive’ and ‘the king of kings.’ She even convinced Bruce Nugent, who hated schools, to attend Boas’s classes. Boas was sixty-seven at the time and had been at Columbia since 1899. He was without a doubt America’s preeminent anthropologist, almost singlehandedly responsible for debunking scientific racism, defining cultural relativism, and establishing folklore as a subject worthy of scientific study. He unflaggingly encouraged Zora’s work, and urged her to become a professional anthropologist herself; undoubtedly he recognized that Zora could well become America’s foremost authority on black folkways.

More here. (Throughout February, at least one post will be dedicated to honoring Black History Month. The theme this year is: The Family)

On Boxing Day 1962 it began to snow and didn’t stop for the next 10 weeks. In effect, Britain had entered its own little ice age. There were drifts 23ft high on the Kent-Sussex border, while Stonehenge was buried so deeply that it was almost invisible when viewed from the sky. Icebergs entered the River Medway and, inland, icicles hung from the trees. The upper middle classes dug out their skis, while everyone else experimented with bits of corrugated iron strapped to their feet. A milkman died at the wheel of his float in Essex while indoor laundry froze before it could dry, so that next week’s vests and pants stood rigidly to attention before the kitchen fire. Someone had calculated that the last time it had been this cold was 1814, the year before Napoleon met his Waterloo.

On Boxing Day 1962 it began to snow and didn’t stop for the next 10 weeks. In effect, Britain had entered its own little ice age. There were drifts 23ft high on the Kent-Sussex border, while Stonehenge was buried so deeply that it was almost invisible when viewed from the sky. Icebergs entered the River Medway and, inland, icicles hung from the trees. The upper middle classes dug out their skis, while everyone else experimented with bits of corrugated iron strapped to their feet. A milkman died at the wheel of his float in Essex while indoor laundry froze before it could dry, so that next week’s vests and pants stood rigidly to attention before the kitchen fire. Someone had calculated that the last time it had been this cold was 1814, the year before Napoleon met his Waterloo.

Lee, or to be formal, Dame Hermione (she was awarded the title in 2013 for “services to literary scholarship”) is a leading member of that generation of British writers — it also includes Richard Holmes, Michael Holroyd, Jenny Uglow and Claire Tomalin — who have brought an infusion of style and imagination to the art of literary biography. She is probably most famous for her

Lee, or to be formal, Dame Hermione (she was awarded the title in 2013 for “services to literary scholarship”) is a leading member of that generation of British writers — it also includes Richard Holmes, Michael Holroyd, Jenny Uglow and Claire Tomalin — who have brought an infusion of style and imagination to the art of literary biography. She is probably most famous for her  Some people think libertarians only care about taxes and regulations. But I was asked not long ago, what’s the most important libertarian accomplishment in history? I said, “the abolition of slavery.”

Some people think libertarians only care about taxes and regulations. But I was asked not long ago, what’s the most important libertarian accomplishment in history? I said, “the abolition of slavery.” Released in the two-hundredth-anniversary year of the signing of the Declaration of Independence,

Released in the two-hundredth-anniversary year of the signing of the Declaration of Independence,  In an equation-dense paper that appeared in The Astrophysical Journal Letters a year after Weryk’s discovery, Loeb and a Harvard postdoc named Shmuel Bialy proposed that ‘Oumuamua’s “non-gravitational acceleration” was most economically explained by assuming that the object was manufactured. It might be the alien equivalent of an abandoned car, “floating in interstellar space” as “debris.” Or it might be “a fully operational probe” that had been dispatched to our solar system to reconnoitre. The second possibility, Loeb and Bialy suggested, was the more likely, since if the object was just a piece of alien junk, drifting through the galaxy, the odds of our having come across it would be absurdly low. “In contemplating the possibility of an artificial origin, we should keep in mind what Sherlock Holmes said: ‘when you have excluded the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth,’ ” Loeb

In an equation-dense paper that appeared in The Astrophysical Journal Letters a year after Weryk’s discovery, Loeb and a Harvard postdoc named Shmuel Bialy proposed that ‘Oumuamua’s “non-gravitational acceleration” was most economically explained by assuming that the object was manufactured. It might be the alien equivalent of an abandoned car, “floating in interstellar space” as “debris.” Or it might be “a fully operational probe” that had been dispatched to our solar system to reconnoitre. The second possibility, Loeb and Bialy suggested, was the more likely, since if the object was just a piece of alien junk, drifting through the galaxy, the odds of our having come across it would be absurdly low. “In contemplating the possibility of an artificial origin, we should keep in mind what Sherlock Holmes said: ‘when you have excluded the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth,’ ” Loeb  Everywhere rare metals are mined – be it the Democratic Republic of Congo (where conditions in the mines are ‘straight out of the Middle Ages’), Kazakhstan or Vietnam – pollution and environmental destruction follow. Safety standards aside, it’s hugely inefficient. Know how much lutetium you’ll get from extracting, crushing and refining 1,200 tonnes of rock? One solitary kilogram.

Everywhere rare metals are mined – be it the Democratic Republic of Congo (where conditions in the mines are ‘straight out of the Middle Ages’), Kazakhstan or Vietnam – pollution and environmental destruction follow. Safety standards aside, it’s hugely inefficient. Know how much lutetium you’ll get from extracting, crushing and refining 1,200 tonnes of rock? One solitary kilogram. Years ago, Maria Stepanova visited the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC to do research for a book she would end up working on for 30 years. After telling him of her plan, the museum adviser replied: “Ah. One of those books where the author travels around the world in search of his or her roots – there are plenty of those now.” “Yes,” replied Stepanova. “And now there will be one more.”

Years ago, Maria Stepanova visited the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC to do research for a book she would end up working on for 30 years. After telling him of her plan, the museum adviser replied: “Ah. One of those books where the author travels around the world in search of his or her roots – there are plenty of those now.” “Yes,” replied Stepanova. “And now there will be one more.” Identical twins have nothing on black holes. Twins may grow from the same genetic blueprints, but they can differ in a thousand ways — from temperament to hairstyle. Black holes, according to Albert Einstein’s theory of gravity, can have just three characteristics — mass, spin and charge. If those values are the same for any two black holes, it is impossible to discern one twin from the other. Black holes, they say, have no hair.

Identical twins have nothing on black holes. Twins may grow from the same genetic blueprints, but they can differ in a thousand ways — from temperament to hairstyle. Black holes, according to Albert Einstein’s theory of gravity, can have just three characteristics — mass, spin and charge. If those values are the same for any two black holes, it is impossible to discern one twin from the other. Black holes, they say, have no hair. When the anthropologist Irven DeVore suggested in 1962 to then-graduate student Richard Lee that they study hunter-gatherers, neither expected to transform the modern understanding of human nature. A baboon expert, DeVore mostly wanted to expand his research to human groups. Lee was searching for a dissertation project. Being interested in human evolution, they decided not to study peoples in the Americas or Australia, as was the norm in hunter-gatherer studies. Instead, they looked for a site that was, in Lee’s words, ‘close to the actual faunal and floral environment occupied by early man’. So, they headed to Africa – specifically, to the Kalahari.

When the anthropologist Irven DeVore suggested in 1962 to then-graduate student Richard Lee that they study hunter-gatherers, neither expected to transform the modern understanding of human nature. A baboon expert, DeVore mostly wanted to expand his research to human groups. Lee was searching for a dissertation project. Being interested in human evolution, they decided not to study peoples in the Americas or Australia, as was the norm in hunter-gatherer studies. Instead, they looked for a site that was, in Lee’s words, ‘close to the actual faunal and floral environment occupied by early man’. So, they headed to Africa – specifically, to the Kalahari. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the 18th-century poet and philosopher, believed life was hardwired with archetypes, or models, which instructed its development. Yet he was fascinated with how life could, at the same time, be so malleable. One day, while meditating on a leaf, the poet had what you might call a proto-evolutionary thought: Plants were never created “and then locked into the given form” but have instead been given, he later wrote, a “felicitous mobility and plasticity that allows them to grow and adapt themselves to many different conditions in many different places.” A rediscovery of principles of genetic inheritance in the early 20th century showed that organisms could not learn or acquire heritable traits by interacting with their environment, but they did not yet explain how life could undergo such shapeshifting tricks—the plasticity that fascinated Goethe.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the 18th-century poet and philosopher, believed life was hardwired with archetypes, or models, which instructed its development. Yet he was fascinated with how life could, at the same time, be so malleable. One day, while meditating on a leaf, the poet had what you might call a proto-evolutionary thought: Plants were never created “and then locked into the given form” but have instead been given, he later wrote, a “felicitous mobility and plasticity that allows them to grow and adapt themselves to many different conditions in many different places.” A rediscovery of principles of genetic inheritance in the early 20th century showed that organisms could not learn or acquire heritable traits by interacting with their environment, but they did not yet explain how life could undergo such shapeshifting tricks—the plasticity that fascinated Goethe. Today’s selection — from Zora and Langston by

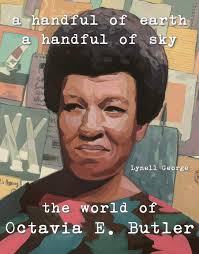

Today’s selection — from Zora and Langston by  Butler was 58 when Fledgling was published, and barely a year later, she fell and hit her head on an icy pavement and died. Her papers arrived at the Huntington in 2008: two filing cabinets and 35 large cardboard boxes, containing drafts, notes, sums, receipts and bills, an order form for men’s-size Star Trek jerseys; to-do lists and to-get lists – ‘Potatoes

Butler was 58 when Fledgling was published, and barely a year later, she fell and hit her head on an icy pavement and died. Her papers arrived at the Huntington in 2008: two filing cabinets and 35 large cardboard boxes, containing drafts, notes, sums, receipts and bills, an order form for men’s-size Star Trek jerseys; to-do lists and to-get lists – ‘Potatoes Madlib has always seemed more concerned with making music than with the question of what to do with it. The forty-seven-year-old producer and multi-instrumentalist has estimated that he makes hundreds of beats a week, many of which he never shares with anyone. His beats are a form of homage. He listens carefully to an old record, trying to squeeze every musical possibility out of it, to follow every path not taken. Sometimes it’s therapeutic. The week that Prince died, Madlib mourned by making tracks built on Prince samples. Following the death of his collaborator J Dilla, and then that of MF DOOM, he stayed awake for days, making hundreds of hours of music. Since the nineties, Madlib has essentially been building a private, ever-expanding library of beats, which spans everything from hip-hop, jazz, and soul to German rock, industrial music, Brazilian funk, and Bollywood. He has released dozens of albums under just as many aliases. Sometimes the aliases splinter off to form side projects. For Madlib, making music is as elemental as eating or sleeping, though he claims to do very little of the latter.

Madlib has always seemed more concerned with making music than with the question of what to do with it. The forty-seven-year-old producer and multi-instrumentalist has estimated that he makes hundreds of beats a week, many of which he never shares with anyone. His beats are a form of homage. He listens carefully to an old record, trying to squeeze every musical possibility out of it, to follow every path not taken. Sometimes it’s therapeutic. The week that Prince died, Madlib mourned by making tracks built on Prince samples. Following the death of his collaborator J Dilla, and then that of MF DOOM, he stayed awake for days, making hundreds of hours of music. Since the nineties, Madlib has essentially been building a private, ever-expanding library of beats, which spans everything from hip-hop, jazz, and soul to German rock, industrial music, Brazilian funk, and Bollywood. He has released dozens of albums under just as many aliases. Sometimes the aliases splinter off to form side projects. For Madlib, making music is as elemental as eating or sleeping, though he claims to do very little of the latter. The Democratic Party’s repudiation of these voters’ views as “deplorable” or “racist” stoked resentment of urban elites, driving many in search of a new political home. When Donald Trump appeared before workers and farmers in his red baseball cap, he articulated their antipathies coarsely but effectively. A louche product of a milieu in which shady real-estate deals skirted the world of organized crime, Trump shared some of the class resentment of people who could only dream of his wealth. Trump became their savior, and tied the Republican Party firmly to hard-right populism. Even without Trump as president, the GOP will remain his party for a long time.

The Democratic Party’s repudiation of these voters’ views as “deplorable” or “racist” stoked resentment of urban elites, driving many in search of a new political home. When Donald Trump appeared before workers and farmers in his red baseball cap, he articulated their antipathies coarsely but effectively. A louche product of a milieu in which shady real-estate deals skirted the world of organized crime, Trump shared some of the class resentment of people who could only dream of his wealth. Trump became their savior, and tied the Republican Party firmly to hard-right populism. Even without Trump as president, the GOP will remain his party for a long time. By the time Mudassir Azeemi wrote to Apple CEO Tim Cook in 2014, he’d tried everything he could think of to make it easier to type in his native language, Urdu. In 2010, the now 42-year-old Pakistani-American developed a keyboard app you could use on iOS devices; within two years, it had been downloaded over 165,000 times. But even with an Urdu-language keyboard, the characters appeared on the screen in an entirely different font.

By the time Mudassir Azeemi wrote to Apple CEO Tim Cook in 2014, he’d tried everything he could think of to make it easier to type in his native language, Urdu. In 2010, the now 42-year-old Pakistani-American developed a keyboard app you could use on iOS devices; within two years, it had been downloaded over 165,000 times. But even with an Urdu-language keyboard, the characters appeared on the screen in an entirely different font.