by Joan Harvey

The new book by Sandor Ellix Katz, Fermentation as Metaphor, is “Dedicated to bubbly excitement, in its infinite effervescent manifestations.” As our Covid Days drag on, I have a dream about champagne flutes gone missing, though I manage to find other glasses that will do. I suspect this is a dream about our current loss of social celebrations, and a wish for the bubbly groupings of the past, but, also, when I find different glasses, how it is still possible to find other ways to bubble (or with glasses how it is possible to see things differently).

“Bubbles create movement, literally exciting the substrate being transformed by the fermentation, bringing it to life” (Katz 80). When our ideas, our spirits, our thoughts bubble up, it shows that something exciting is taking shape. Fermentation is from the latin fervere, which means to boil. It’s all about the bubbles. We even live in an age of bubbles: the German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk has written a 664-page tome called Bubbles, the first of a three-part trilogy, a theory of relationship and intimacy that takes us from the womb to the Christian conception of God; the Flaming Lips performed a concert in which every musician and each person in the audience was encased in a bubble, and I, for one, live in a liberal bubble. But Sandor Katz’s bubbles have energy, permeability, and an excitement that is very much shared, rather than isolating.

Katz is the author of several award-winning books on fermentation and the star of many wonderful YouTube videos. I’ve heard him speak; he’s one of those people who can clearly call out bullshit and yet somehow remain kind while doing it. He has a very large following, no doubt due to his openness, his lack of fussiness, his honesty, and his humor. He’s also a wonderful writer and storyteller; I’m always surprised at the number of people who know his work and who adore him. An urban NYC kid, he later lived on a commune in Tennessee for 17 years, with a group of people who called themselves the Radical Faeries. As an article by Alex Halberstadt in the New York Times reports, “With its outhouses, goats and vegetable gardens, it doesn’t appear far different from your textbook commune. Until, that is, you hear about a spot called Sex Change Ridge, a network of hiking trails called the Fruit Loop and a functionary called the Empress.”

As a young man in New York, Katz developed HIV, and became a member of ACT UP. He quit his job in government in NYC, moved to Tennessee and the commune, and discovered that fermented foods could help the immune system. At the commune he also learned how to do practical things. As Halberstadt wrote, “‘Urban gay men have become a deskilled class,’ he said. ‘Having to learn these traditionally masculine skills was hugely empowering.’ Sometime after he arrived at the faerie sanctuary, Katz and his friends began calling it the Short Mountain Refinishing School for the Butch Arts.”

I happen to have a mother well established in the butch arts, who built much of our furniture, and who was never happier than when the pump broke and we had to haul water from the ditch. Today, at age 89, she lives in a more modern house and often complains that nothing breaks, so that she has nothing to do. When she moved from our old house into this smaller one, my brother noted that she took with her three pairs of shoes and five crowbars. In contrast, for better or worse, after a childhood of chinking and caulking and thistle pruning, I’ve turned out to be a femme who likes to leave the carpentry and plumbing to men and women who enjoy this stuff, though I confess, when I do manage some kind of practical behavior, I get a kind of thrill (and I am oddly good at troubleshooting mechanical systems; I suspect I’d have made a good appliance repairman). But mostly I’m not any kind of pioneer. I tried making sauerkraut once, and it wasn’t very good. Being a person who lives more in her head than in the kitchen, fermentation as metaphor is much more up my alley than fermentation as growing and slicing and salting vegetables and waiting to see how they turn out. But I have both of Katz’s earlier hands-on, down and dirty books about making fermented food oneself in case I should undergo a violent, or even gentle, personality change.

One of the best things about Katz is how refreshingly undogmatic he is. He doesn’t value rural life over city life, or one type of diet over another; he’s not any kind of puritan or purist. Quite the opposite, in fact. In videos he is shown plunging his hands into various wicked brews, sometimes removing mold and exclaiming happily. Fermentation involves bacteria, mixing of substances, transformation. It’s a way of breaking boundaries, and it shows us the interconnectivity of everything. Obviously this makes a lot available for metaphor.

Much of Katz’s discussion has to do with the benefits of contamination, and how actually there is no such thing as purity, except as abstraction. The roots of contamination, con—with, and tangere — to touch, are actually quite lovely. And germs, Katz reminds us, are from Latin germinus, to sprout or germinate. Fermentation takes place when bacteria break down material and transform it; in a completely sterile environment there would be no fermentation. And unless separated out by humans, microorganisms don’t act as singular agents, but rather in groups that are always shifting and exchanging genetic material, trading identities to some degree. For Katz this is a useful metaphor for how we can become more fluid in our lives and interactions: “That’s what metaphorical fermentation is, an infinite source of mutation, transformation, and regeneration” (108). Old structures break down and give rise to new forms, and those in turn break down as well.

Just as childhood exposure to diverse microorganisms can help protect against allergies, asthma, and other autoimmune diseases, so exposure to a diversity of different people can inoculate against racism and closed-mindedness. Katz reminds us food is not clean, children are not pure, sexuality should not be suppressed. He even has sections on body odors and farting, though he does not go so far as to use farting as metaphor. Purist fantasies of race, blood, nation, culture, are just that, fantasies. We recently learned that many of us are not even pure Homo sapiens; our ancestors got down and dirty with some hairy Neanderthals.

Katz reminds us that there is much more fluidity between things than we acknowledge. “Bacteria and fungi and the broader microbial communities in which they exist exemplify adaptability and constant change; and fermentation offers potent metaphors for imagining change and communicating about it so that we may take collective action” (49). Just as the process of fermentation can create alcohol, make food more easily digestible, and break down toxic compounds into harmless substances, metaphorical fermentation is about generating new forms. Among these is the breakdown of our old binary thinking, which we see in our current clearer understanding of people who are neurodivergent or differently abled, as well as those who are gender fluid or transgender.

For Katz, a feeling of shared effervescence can be an engine of social change:

When a group of people whose reality has been pathologized organize to claim respect for who they are, that is fermentation. Individual thoughts compel people into conversations that bubble and spread and bubble some more. . . For any group of people who share a feeling that they are being misunderstood or misrepresented, joining together to assert how they wish to identify is powerful and transformative fermentation (94, 96).

It is interesting how often trans people, who so obviously have experienced great transformation, are in the forefront of social movements. Civil rights and women’s rights activist Pauli Murray is a good example, as were Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson in the queer liberation movement in New York City. Today a new younger crop of trans activists are taking the lead.

Fermentation, however, cannot be controlled, and movements on the right, such as the Proud Boys, also involve a kind of bubbly excitement. Cabbage can become sauerkraut or slime. In general, authoritarian regimes attempt to suppress bubbly cultural expressions except where it can be channeled into sanctioned forms. Fortunately total social control is impossible. The future, Katz reminds us, belongs to the flexible.

Fermentation is also a handy metaphor for thinking. A piece of exciting writing, an image, a lively conversation, combine in a brew that, if cared for and harvested properly, can result in a brand new thought with a zesty taste. “Critical thinking is a form of fermentation. The ideas or information or stories we are presented with are the substrate. Our interrogation of them, whether silently in reflection, or aloud as questions or challenges, is the bubbly agitation” (Katz, 86). For some of us the question is whether these ideas will make a tasty ferment, or devolve into some unpalatable mess?

Katz also puts forward the idea of emotional composting. “Like food scraps and weeds in a compost pile, feelings can ferment into new ones that enable us to heal and grow” (90). I recently learned of a theory of Polish psychologist Kazimierz Dąbrowski, which contains two elements that can be mapped onto fermentation: positive disintegration and overexcitement. Just as bacteria break down food sources and transform them into even better things, so certain psychological breakdowns in humans can, according to Dąbrowski, lead to better self-understanding and better lives. In Dąbrowski’s scheme, overexcitability is a positive part of this. According to Dąbrowski, “Individuals with overexcitabilities have a greater potential for personal development because they foster a different perspective on the world and drive a more personal and meaningful interpretation of one’s experiences” (Dąbrowski, 1972).” Even the experience Katz had of getting HIV and then completely changing his life to one more perfectly suited to his own individuality fits with Dąbrowski’s theories of disintegration and then reintegration in a better way.

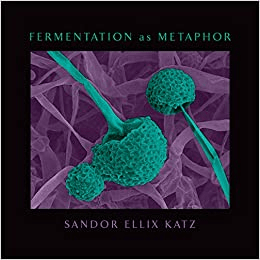

Almost half of Fermentation as Metaphor is comprised of full-page illustrations, photos Katz took with a scanning electron microscope which were then colorized. The high magnification shows us the complexity of the structure of membranes, and strips away their sharp dividing lines. Our appreciation of the photos and their sometimes gorgeous colors— a deep red and bright yellow image of filaments playfully dotted at the ends turns out to be a photo of moldy cornbread —is no doubt partly influenced by our familiarity with abstract art. I’m reminded of an essay on abstract expressionism by the artist Amy Sillman, on messiness and contingency in this type of painting and how much the body is involved. Katz’s books are all about taking things into your own hands, making stuff, combining things in new ways to see how they turn out. Sillman says of abstract expressionism, “AbEx was simply one technique of the body for those dedicated to the handmade, a way to throw shit down, mess shit up, and perform aggressive erasures and dialectical interrogations.”

Stillman recounts how after an unpopular talk she gave on form, to art students who were more interested in political content, a few bearded guys came up afterwards to say they loved it. Later she found out they were transgendered men. “It was funny for me to realize that the people who loved my formalist rap the most were the guys who had gone the furthest in their own personal lives to make specific changes to their own forms. We were both committed to an idea of the inseparability of form and content, and we were working with their interactions, their malleability…”

Being open to transforming our ideas of beauty shows us that there is beauty even in decay, as demonstrated by Katz’s photographs. Decomposition is an essential part of the chain of life. Kathleen Ryan’s sculptures of oversized rotting fruit, made from beads and semiprecious stones, gorgeous and terrible at the same time, work in the opposite way, turning organic decay into something solid, and also useful as metaphor. As described in the New York Times:

They’re not just opulent, there’s an inherent sense of decline built into them,” Ryan says, “which is also something that’s happening in the world: The economy is inflating, but so is wealth inequality, all at the expense of the environment.” Tellingly, while she uses manufactured glass beads to create patches of ripe skin, the more expensive, naturally occurring gemstones are reserved for the rot. “Though the mold is the decay,” she says, “it’s the most alive part.”

Katz tells us we must reclaim our ancestral connection to the unseen microbial world. I have been hanging with some poets investigating ancestors, but I haven’t gone so far as to investigate my microbial family tree. On the other hand, at my mother’s 80th birthday party I gave a speech about how there are ten times as many bacterial cells as human cells in the body, so therefore my mother was only 10 percent human. This did not go over well, though I did mention fermentation in terms she appreciated, those of a good Bordeaux or a cognac that has sloshed around the world on multiple sea voyages.

Fermentation also involves patience and containers, two things Katz does not much discuss, and there is room for more metaphorical pondering. Even those of us who are not particularly patient know that when we’re upset (or infatuated) it is often best to wait to see what brews out of these feelings, rather than exposing them untransformed and too soon. On the other hand, if we simply lock them up in some inner container and never tend them or let them out, they can molder in an unconscious and detrimental way. Our unconscious is another invisible agency that works on us, transforming us without our conscious action or knowledge. We can also think about becoming or making the kind of containers that can best ferment movements and ideas. There is more to be explored.

The main message of Fermentation as Metaphor is the value of cultivating a rebellious spirit. Learn to enjoy dirt and contamination, refuse to tamp down the effervescence that leads to social movements, mix and mingle and ferment with others (but continue to wear a mask) in both transformation and delight.