Month: September 2020

Sunday Poem

The Mad Yak

I am watching them churn the last milk they’ll ever get from me.

They are waiting for me to die;

They want to make buttons out of my bones.

Where are my sisters and brothers?

That tall monk there, loading my uncle, he has a new cap.

And that idiot student of his–

I never saw that muffler before.

Poor uncle, he lets them load him.

How sad he is, how tired!

I wonder what they’ll do with his bones?

And that beautiful tail!

How many shoelaces will they make of that!

Stephen F. Cohen, 1938–2020

Katrina vanden Heuvel in The Nation:

Katrina vanden Heuvel in The Nation:

I first “met” Steve through his 1977 essay “Bolshevism and Stalinism.” His cogent, persuasive, revisionist argument that there are always alternatives in history and politics deeply influenced me. And his seminal biography, Bukharin and the Bolshevik Revolution, challenging prevailing interpretations of Soviet history, was to me, and many, a model of how biography should be written: engaged and sympathetically critical.

At the time, I was too accepting of conventional wisdom. Steve’s work—and soon, Steve himself—challenged me to be critical-minded, to seek alternatives to the status quo, to stay true to my beliefs (even if they weren’t popular), and to ask unpopular questions of even the most powerful. These are values I carry with me to this day as editorial director of The Nation, which Steve introduced me to (and its editor, Victor Navasky) and for which he wrote a column (“Sovieticus”) from 1982 to 1987, and many articles and essays beginning in 1979. His last book, War with Russia? was a collection of dispatches (almost all posted at thenation.com) distilled from Steve’s weekly radio broadcasts—beginning in 2014–on The John Batchelor Show.

The experiences we shared in Moscow beginning in 1980 are in many ways my life’s most meaningful. Steve introduced me to realms of politics, history, and life I might never have experienced: to Bukharin’s widow, the extraordinary Anna Mikhailovna Larina, matriarch of his second family, and to his eclectic and fascinating circle of friends—survivors of the Gulag, (whom he later wrote about in The Victims Return) dissidents, and freethinkers—both outside and inside officialdom.

More here.

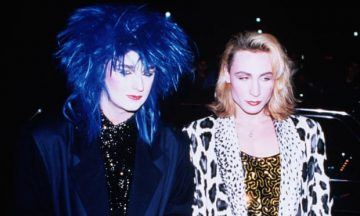

The Story of The New Romantics

Alexis Petridis at The Guardian:

Sweet Dreams tactfully sidesteps whether some of the New Romantics mirrored the celebrity-for-celebrity’s sake aspirations of many of today’s vloggers and influencers. But Jones makes a convincing case that their penchant for what used to be called “gender-bending” and their sartorial obsession with self-expression as “a platform for identity” foreshadows a lot of 2020’s hot-button topics. The book is excellent on the movement’s origins both in the aspirational teenage style cult that built around Bryan Ferry in the mid-70s and the more fashion-forward occupants of the same era’s gay clubs and soul nights, who saw the clothes Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood sold in their boutique Sex not as harbingers of spittle-flecked youth revolution but as a particularly outrageous brand of couture: it’s often written out of punk’s history that, at precisely the same time the Sex Pistols’ career was getting underway, there were people in Essex dancing to disco dressed exactly like Johnny Rotten.

Sweet Dreams tactfully sidesteps whether some of the New Romantics mirrored the celebrity-for-celebrity’s sake aspirations of many of today’s vloggers and influencers. But Jones makes a convincing case that their penchant for what used to be called “gender-bending” and their sartorial obsession with self-expression as “a platform for identity” foreshadows a lot of 2020’s hot-button topics. The book is excellent on the movement’s origins both in the aspirational teenage style cult that built around Bryan Ferry in the mid-70s and the more fashion-forward occupants of the same era’s gay clubs and soul nights, who saw the clothes Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood sold in their boutique Sex not as harbingers of spittle-flecked youth revolution but as a particularly outrageous brand of couture: it’s often written out of punk’s history that, at precisely the same time the Sex Pistols’ career was getting underway, there were people in Essex dancing to disco dressed exactly like Johnny Rotten.

more here.

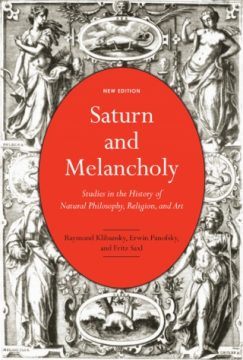

The Secret Life of Saturn: Melancholia and the Warburg Institute

P.S. Makhlouf at Marginalia Review:

If melancholia may be “[s]ometimes painful and depressing, sometimes merely mildly pensive or nostalgic,” then this new edition is, in its own right, a melancholic exercise, a wistful homage to the once-world in which the book was produced. It is also melancholic from the perspective of the contemporary reader who is able to fathom the shear catholicity of mind necessary to produce a Meisterwerk of this sort. But it is in fact that very nostalgia that is in question in the book proper, for the study lays out just how persistently the posture of scholar, artist and anchorite alike has been one of despair at the path that separates them from the great transcendence lying on the horizon, whether that goes by the name of God, the eternal intellect or the Mallarmean “Book.” And in this respect, the history of melancholy itself joins up with the story of the long, arduous path by which the book came into being.

If melancholia may be “[s]ometimes painful and depressing, sometimes merely mildly pensive or nostalgic,” then this new edition is, in its own right, a melancholic exercise, a wistful homage to the once-world in which the book was produced. It is also melancholic from the perspective of the contemporary reader who is able to fathom the shear catholicity of mind necessary to produce a Meisterwerk of this sort. But it is in fact that very nostalgia that is in question in the book proper, for the study lays out just how persistently the posture of scholar, artist and anchorite alike has been one of despair at the path that separates them from the great transcendence lying on the horizon, whether that goes by the name of God, the eternal intellect or the Mallarmean “Book.” And in this respect, the history of melancholy itself joins up with the story of the long, arduous path by which the book came into being.

more here.

Slavoj Žižek. On Melancholy.

Understanding Chris Marker’s Radical Sci-Fi Film La Jetée: A Study Guide Distributed to High Schools in the 1970s

Colin Marshall in Open Culture:

Pop quiz, hot shot. World War III has devastated civilization. As a prisoner of survivors living beneath the ruins of Paris, you’re made to go travel back in time, to the era of your own childhood, in order to secure aid for the present from the past. What do you do? You probably never faced this question in school — unless you were in one of the classrooms of the 1970s that received the study guide for Chris Marker’s La Jetée. Like the innovative 1962 science-fiction short itself, this educational pamphlet was distributed (and recently tweeted out again) by Janus Films, the company that first brought to American audiences the work of auteurs like Ingmar Bergman, Federico Fellini, and Akira Kurosawa.

Written by Connecticut prep-school teacher Tom Andrews, this study guide describes La Jetée as “a brilliant mixture of fantasy and pseudo-scientific romance” that “explores new dramatic territory and forms, and rushes with a stunning logic and a powerful impact to its shocking climax.”

The film does all this “almost entirely in still photographs, their static state corresponding to the stratification of memory.” More practically speaking, at “twenty-seven minutes in length, La Jetée is an ideal class-period vehicle” that “can help students speculate on the awesome potential of life as it may exist after a third world war” as well as “man’s inhumanity to man, not only as it may occur in the future, but as it already has occurred in our past.”

More here.

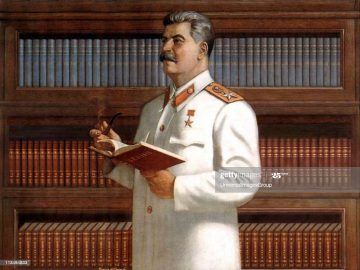

Why tyrants love to write poetry

Benjamin Ramm in the BBC:

Poetry is an art of refinement, synonymous with delicacy and sensitivity. It seems counterintuitive that it might also be a celebration of brutality, and the art form beloved of tyrants. But from classical antiquity to modernity, dictators have been inspired to write verse – seeking solace, intimacy, or glory. Their work informs us about the nature of power, the abiding appeal of poetry, and the perils of artistic interpretation.

The archetype of the poet-tyrant is Roman emperor Nero (37-68 CE), the vain, self-pitying exhibitionist whose debased rule mirrored his deficient art. Nero’s historiographers, Tacitus and Suetonius, suggest that Rome was as tormented by his poetry as by his policies. Derision

is a satisfying form of critical revenge, but these accounts raise a troubling question: would the tyrant’s crimes be mitigated were his art deemed to have merit; and conversely, can we judge fairly the quality of a tyrant’s poetry?

More here.

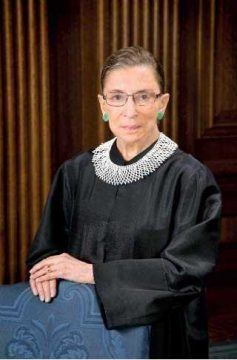

The not-so-notorious RBG

Radhika Coomaraswamy in Daily FT (Sri Lanka):

Radhika Coomaraswamy in Daily FT (Sri Lanka):

A diminutive, shy person with head bowed down walked into the room. She walked slowly but with a purposive step. When she began the class her voice was just above a whisper and her words were accompanied by long pauses as we strained to listen. This was 1976 and I was enrolled in the class of Professor Ruth Bader Ginsburg as she began her pioneering course on sex-based discrimination and the law.

As a South Asian I was used to vibrant and colourful women leaders. Ginsburg was anything but. With a cold, piercing, powerful, intellect, she showed us how to dissect arguments, plan a cohesive strategy and win the battle. She was all about the analysis, the details and the hard work. Her main area of interest in the law was Civil Procedure, the rules and processes of the legal system. I usually fell asleep during those classes but it was Ginsburg who convinced me that if you are going to be a human rights lawyer, first master the procedure. Your passion will guide the substance.

More here.

The world’s top 50 thinkers 2020: the winner

From Prospect Magazine:

It’s a disease of the body, but it has redefined the requirements for a great mind. In the last issue, we renewed a Prospect tradition and identified 50 top world thinkers. It was an all-new list for the Covid-19 age, since the mood called for thinking of a different sort—less chin-stroking, more hands on. Then 20,000-odd votes were cast and counted in a public ballot. The results are in, and represent a landslide win for the practical minds party. The top spot was overwhelmingly secured by a figure who—on first blush—is as far from a caricature intellectual of the Jean-Paul Sartre variety as you can get. That’s not quite right since, like Sartre, KK Shailaja is a communist, albeit from a party created to keep its distance from Soviet Moscow. It helps run the state of Kerala in south India, where Shailaja or “Teacher,” as she is fondly nicknamed due to a previous occupation, is the indefatigable health minister.

It’s a disease of the body, but it has redefined the requirements for a great mind. In the last issue, we renewed a Prospect tradition and identified 50 top world thinkers. It was an all-new list for the Covid-19 age, since the mood called for thinking of a different sort—less chin-stroking, more hands on. Then 20,000-odd votes were cast and counted in a public ballot. The results are in, and represent a landslide win for the practical minds party. The top spot was overwhelmingly secured by a figure who—on first blush—is as far from a caricature intellectual of the Jean-Paul Sartre variety as you can get. That’s not quite right since, like Sartre, KK Shailaja is a communist, albeit from a party created to keep its distance from Soviet Moscow. It helps run the state of Kerala in south India, where Shailaja or “Teacher,” as she is fondly nicknamed due to a previous occupation, is the indefatigable health minister.

So deft was her handling of a 2018 outbreak of the deadly Nipah disease that it was commemorated in a film, Virus. In 2020, she was the right woman in the right place. When Covid-19 was still “a China story” in January, she not only accurately foresaw its inevitable arrival, but also fully grasped the implications. She rapidly got the WHO’s full “test, trace and isolate” drill implemented in the state, and bought crucial time by getting a grip of the airports, and containing the first cases to arrive on Chinese flights. Of course the virus returned, but there was rigorous surveillance and quarantine—sometimes in makeshift structures. The public messages have been consistent, and Shailaja follows them to the letter, with social distancing in all official meetings (which can go on until 10pm) and restricting herself to a Zoom-only relationship with her grandchildren.

More here.

How Can We Bear This Much Loss?

Amitha Kalaichandran in The New York Times:

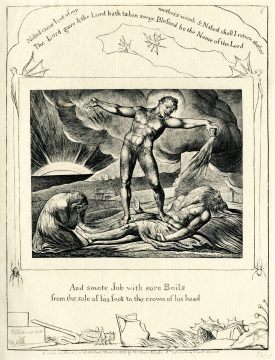

I thought of the biblical story of Job last month when I was asked to speak to the National Partnership for Hospice Innovation. How would I counsel others to cope with losses so terrifying and unfair? How could those grieving find a sense of hope or meaning on the other side of that loss? In my research I found myself drawn to the powerful rendition of the Book of Job by the 18th-century British poet, artist and mystic William Blake, in particular his collection of 22 engravings, completed in 1823, that include beautiful calligraphy of biblical verses. Job, of course, is the Bible’s best-known sufferer. His bounty — home, children, livestock — is taken cruelly from him as a test of faith devised by Satan and carried out by God. He suffers both mental and physical illness; Satan covers him in painful boils.

I thought of the biblical story of Job last month when I was asked to speak to the National Partnership for Hospice Innovation. How would I counsel others to cope with losses so terrifying and unfair? How could those grieving find a sense of hope or meaning on the other side of that loss? In my research I found myself drawn to the powerful rendition of the Book of Job by the 18th-century British poet, artist and mystic William Blake, in particular his collection of 22 engravings, completed in 1823, that include beautiful calligraphy of biblical verses. Job, of course, is the Bible’s best-known sufferer. His bounty — home, children, livestock — is taken cruelly from him as a test of faith devised by Satan and carried out by God. He suffers both mental and physical illness; Satan covers him in painful boils.

Job is conflicted — at times he still has his faith and trusts in God’s wisdom, and other times he questions whether God is corrupt. Finally, he demands an explanation. God then allows Job to accompany him on a tour of the vast universe where it becomes clear that the universe in which he exists is more complex than the human mind could ever comprehend. Though Job still doesn’t have an explanation for his suffering, he has gained some peace; he’s humbled. Then God returns all that Job has lost. So, the story is, in large part, about the power of one man’s faith. But that’s not all.

…It’s also about our attachments — to our identities, our faith, the possessions and people we have in our lives. Grief is a symptom of letting go when we don’t want to. Understanding that attachment is the root of suffering — an idea also central to Buddhism — can give us a glimpse of what many of us might be feeling during this time.

More here.

Saturday Poem

Charlie Parker (1950)

Bird is building a metropolis with his horn.

Here are the gates of Babylon, the walls of Jericho cast down.

Might die in Chicago, Kansas City’s where I was born.

Snowflake in a blizzard, purple rose before the thorn.

Stone by stone, note by note, atom by atom, noun by noun,

Bird is building a metropolis with his horn.

Uptown, downtown, following the river to its source,

Savoy, Three Deuces, Cotton Club, Lenox Lounge.

Might just die in Harlem, Kansas City’s where I was born.

Bird is an abacus of possibility, Bird is riding the horse

of habit and augmented sevenths. King without a crown,

Bird is building a metropolis with his horn.

Bred to the labor of it, built to claw an eye from the storm,

made for the lowdown, the countdown, the breakdown.

Might die in Los Angeles, Kansas City’s where I was born.

Bridge by bridge, solo by solo, set by set, chord by chord,

woodshed to penthouse, blue to black to brown,

Charlie Parker is building a metropolis with his horn.

Might just die in Birdland, Kansas City’s where I was born.

by Campbell McGrath

from the Academy of American Poets

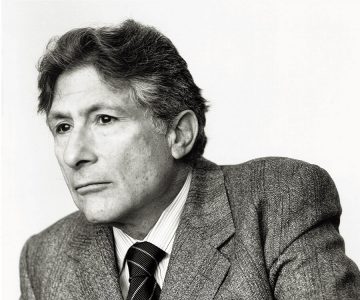

Edward Said: American Intellectual, Palestinian Patriot, Breaker of Dogmas

Khaled Beydoun in Newsweek:

Edward Said, who died 17 years ago today, has been called many things. A literary critic and an exile, an unyielding voice for Palestinian self-determination, an educator, a trailblazer, a “normalizer”—and even “a prophet of the political violence” unfolding in the United States today, seventeen years after he took his final breath.

During a lifetime that spanned nearly sixty-eight years and witnessed definitive geopolitical currents and shifts, Said stood apart as one of the world’s most incisive public intellectuals. A Palestinian by birth and an American by choice, Said took on this role in the early 1980’s following the publication of Orientalism, a text that dismantled European misrepresentations of Islam in its annals of literature.

This moment converged with the aftermath of the Iranian hostage crisis and ascendance of the Islamic Republic of Iran, which reoriented the whole of Islam as the “enemy of the West.” And in turn, propelled Said and his work onto the center of the public stage.

More here.

Read about and watch 31 Buster Keaton Films Online free

Josh Jones in Open Culture:

In 1987, Video magazine published a story titled “Where’s Buster?” lamenting the lack of Buster Keaton films available on videotape, “despite renewed interest” in a legend who was “about to regain his rightful place next to Chaplin in silent comedy’s pantheon.” How things have changed for Keaton fans and admirers. Not only are most of the stone-faced comic genius’ films available online, but he has maybe eclipsed Chaplin as the most popularly revered silent film star of the 1920s.

Keaton has always been held in the highest esteem by his fellow artists. He was dubbed “the greatest of all the clowns in the history of the cinema” by Orson Welles, and served as a significant inspiration for Samuel Beckett. (He was the playwright’s first choice to play Waiting for Godot’s Lucky, though he was too perplexed by the script to take the role). In Peter Bogdanovich’s new documentary, The Great Buster: A Celebration, Mel Brooks and Carl Reiner discuss his foundational influence on their comedy, and Werner Herzog calls him “the essence of movies.”

More here.

Why Covid is at least 10 times more deadly than the flu

Rod Jackson in the New Zealand Herald:

Estimates of the proportion of people who die from Covid-19 have been controversial, with some even dismissing it as similar to a bad flu. There are three main problems accounting for this controversy.

Estimates of the proportion of people who die from Covid-19 have been controversial, with some even dismissing it as similar to a bad flu. There are three main problems accounting for this controversy.

In this article, I describe each of these problems and some of the ways that epidemiologists such as me me try to deal with them.

Problem 1: To calculate the proportion of people who have been infected with Covid-19 and who die as a result (the Infection Fatality Proportion), you need two numbers – the number of deaths (the numerator) and the number of people who have been infected (the denominator) and then you divide the numerator by the denominator.

It sounds simple, but unfortunately accurate information on both these numbers for Covid-19 is hard to find, unless you know what to look for. Just for the record, I have used the correct epidemiological term – the “Infection Fatality Proportion” not the “Infection Fatality Rate” – because it’s not actually a rate. In epidemiology, a rate requires a time component, for example, 10 deaths per 1000 people per year.

More here.

Sean Carroll: Quantum Worlds & the Emergence of Spacetime

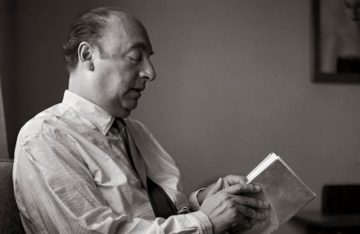

Neruda in Ceylon: On making peace (of sorts) with Pablo Neruda

Robina P Marks in the Sri Lanka Guardian:

My love for your poetry is complicated further, because the memory of a Tamil woman called Thangamma keeps casting a dark shadow of fear and menace over your work. She darts and dives between the lines of your poems with an angry, restless spirit that will not cease.

My love for your poetry is complicated further, because the memory of a Tamil woman called Thangamma keeps casting a dark shadow of fear and menace over your work. She darts and dives between the lines of your poems with an angry, restless spirit that will not cease.

Thangamma, the woman who would come every morning to your house next to the sea to collect buckets of your human waste, and those of others in your street. Thangamma, that you dreamt of possessing, and to whom you offered endless gifts of fruit and silk that she ignored. Until one day, as you recall in your writing, when you gripped her hard by her wrists. You described this vividly:

“Unsmiling, she let herself be led away and soon was naked in my bed. Her waist, so very slim, her full hips, the brimming cups of her breasts made her like one of the thousand-year-old sculptures from the south of India… She kept her eyes wide open all the while, completely unresponsive. She was right to despise me. The experience was never repeated.”

And then you continued with an account of the rest of your life, in your memoir, as if this was of no consequence, and just a momentarily regrettable incident. Did you think that saying “she was right to despise me” somehow absolved you from this act of rape?

More here.

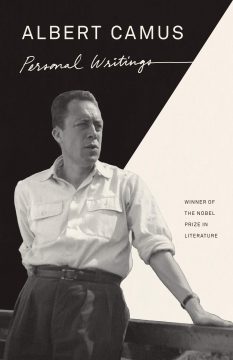

Albert Camus: The Madness of Sincerity

For Camus, It Was Always Personal

Robert Zaretsky at the LARB:

In her sharp and sympathetic foreword, Alice Kaplan observes that, for readers who know Camus only as the author of The Stranger, the “lush emotional intensity of these early essays and stories will come as a surprise.” Yet I confess that, even for someone who knew this side of Camus, I was again, as I reread the pieces, surprised by their Dionysian intensity.

In her sharp and sympathetic foreword, Alice Kaplan observes that, for readers who know Camus only as the author of The Stranger, the “lush emotional intensity of these early essays and stories will come as a surprise.” Yet I confess that, even for someone who knew this side of Camus, I was again, as I reread the pieces, surprised by their Dionysian intensity.

The lyricism is especially bracing today, when even Dionysus would think twice before throwing a bacchanalia. For Camus, the lyrical sentiments were deeply rooted in the physical and human landscape of his native Algeria. They flowed from the childhood he spent in a poor neighborhood of Algiers, where he was raised by an illiterate and imperious grandmother and a deaf and mostly mute mother in a sagging two-story building, whose cockroach-infested stairwell led to a common latrine on the landing.

more here.

The Many Faces of Ethan Hawke

John Lahr at The New Yorker:

Throughout his career, Hawke has consistently challenged himself to grow. He has appeared in more than eighty movies, predominantly independent films interspersed with Hollywood money-makers. He has directed four films, written three novels, and co-founded a theatre company. In the process, Hawke has been nominated for four Academy Awards (including two for Best Adapted Screenplay) and a Tony, for his performance, in Tom Stoppard’s trilogy “The Coast of Utopia,” as Mikhail Bakunin, the revolutionary Russian anarchist, whose bowwow personality resurfaces in the fulminations of Hawke’s John Brown. The range of Hawke’s roles—a romantic charmer (in the “Before” trilogy), a drug-addled Chet Baker (in “Born to Be Blue”), a guilt-ridden suicidal priest (in “First Reformed”), to name just a few—is also a reflection of his expansive empathy. “Acting, at its best, is like music,” he said. “You have to get inside your character’s song.”

Throughout his career, Hawke has consistently challenged himself to grow. He has appeared in more than eighty movies, predominantly independent films interspersed with Hollywood money-makers. He has directed four films, written three novels, and co-founded a theatre company. In the process, Hawke has been nominated for four Academy Awards (including two for Best Adapted Screenplay) and a Tony, for his performance, in Tom Stoppard’s trilogy “The Coast of Utopia,” as Mikhail Bakunin, the revolutionary Russian anarchist, whose bowwow personality resurfaces in the fulminations of Hawke’s John Brown. The range of Hawke’s roles—a romantic charmer (in the “Before” trilogy), a drug-addled Chet Baker (in “Born to Be Blue”), a guilt-ridden suicidal priest (in “First Reformed”), to name just a few—is also a reflection of his expansive empathy. “Acting, at its best, is like music,” he said. “You have to get inside your character’s song.”

more here.