by N. Gabriel Martin

Is it still possible today, in the age of widespread and outlandish conspiracy theories, algorithmically induced filter-bubbles, and bullshitting demagogues, a generation after the US Republican party adopted a strategy of unprincipled obstructionism to anything that their democratic counterparts proposed, to believe that reason has a place in politics? When we are so polarised that finding any relevant common ground with our opponents at all is a far-fetched notion, it seems naive to think that it is still possible to move politics by making good arguments. If that were true, then there would be nothing more to politics than might making right. However, pessimism about political reason is only partially justified. While our ability to resolve political disagreements using reason is in crisis, other aspects of public debate are more vital than they have been in generations.

In the aftermath of the breakdown of the political consensus that dominated the broadcast era and persisted for a while into the internet age it is hard to be credulous about resolving disagreement by appealing to opponents’ reason. It’s not possible today, as it once was, to appeal to a common ground of faith in political and cultural institutions in order to bring opponents over to one’s side. The fragmentation and polarisation of the media landscape, contests over the validity of governmental institutions (such as the courts or elections) previously widely considered neutral, and denial of the credibility of experts have left us without much common ground. That’s true, even though we still share many beliefs and values. Politicians and commentators from across the political spectrum talk about the same values, such as democracy, freedom, and life, but on their own, without shared institutions to provide a common understanding of what threatens and what nurtures those values, shared values themselves are too hollow to help us resolve conflicts. The current battle over the legitimacy of the election shows how defence of a grand and nebulous value like democracy can be claimed by either side. Without trust in the expertise and neutrality of institutions, it is impossible for most of us to determine which purported threats to democracy are real and which are fake. Read more »

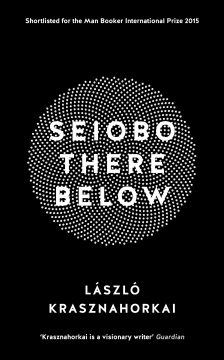

The stories in Seiobo There Below, if they can be called stories, begin with a bird, a snow-white heron that stands motionless in the shallow waters of the Kamo River in Kyoto with the world whirling noisily around it. Like the center of a vortex, the eye in a storm of unceasing, clamorous activity, it holds its curved neck still, impervious to the cars and buses and bicycles rushing past on the surrounding banks, an embodiment of grace and fortitude of concentration as it spies the water below and waits for its prey. We’ve only just begun reading this collection, and already László Krasznahorkai’s haunting prose has submerged us in the great panta rhei of life—Heraclitus’s aphorism that everything flows in a state of continuous change.

The stories in Seiobo There Below, if they can be called stories, begin with a bird, a snow-white heron that stands motionless in the shallow waters of the Kamo River in Kyoto with the world whirling noisily around it. Like the center of a vortex, the eye in a storm of unceasing, clamorous activity, it holds its curved neck still, impervious to the cars and buses and bicycles rushing past on the surrounding banks, an embodiment of grace and fortitude of concentration as it spies the water below and waits for its prey. We’ve only just begun reading this collection, and already László Krasznahorkai’s haunting prose has submerged us in the great panta rhei of life—Heraclitus’s aphorism that everything flows in a state of continuous change.

by Callum Watts

by Callum Watts

“Battle of Algiers”, a classic 1966 film directed by Gillo Pontecorvo, seized my imagination and of my classmates as well when it was shown three years later at the Palladium in Srinagar. A teenager wearing bell-bottoms, dancing the twist, I was a Senior at Sri Pratap College, named after Maharajah Pratap Singh, a Hindu Dogra ruler of Muslim majority Kashmir.

“Battle of Algiers”, a classic 1966 film directed by Gillo Pontecorvo, seized my imagination and of my classmates as well when it was shown three years later at the Palladium in Srinagar. A teenager wearing bell-bottoms, dancing the twist, I was a Senior at Sri Pratap College, named after Maharajah Pratap Singh, a Hindu Dogra ruler of Muslim majority Kashmir.

It’s uncontroversial among biologists that many species have two, distinct biological sexes. They’re distinguished by the way that they package their DNA into ‘gametes’, the sex cells that merge to make a new organism. Males produce small gametes, and females produce large gametes. Male and female gametes are very different in structure, as well as in size. This is familiar from human sperm and eggs, and the same is true in worms, flies, fish, molluscs, trees, grasses and so forth.

It’s uncontroversial among biologists that many species have two, distinct biological sexes. They’re distinguished by the way that they package their DNA into ‘gametes’, the sex cells that merge to make a new organism. Males produce small gametes, and females produce large gametes. Male and female gametes are very different in structure, as well as in size. This is familiar from human sperm and eggs, and the same is true in worms, flies, fish, molluscs, trees, grasses and so forth. Over a decade ago, California put a price on carbon pollution. At first glance the policy appears to be a success: since it began in 2013, emissions have declined by more than

Over a decade ago, California put a price on carbon pollution. At first glance the policy appears to be a success: since it began in 2013, emissions have declined by more than

Maybe my book is rotten,” F Scott Fitzgerald told a friend, in February 1925, shortly before the publication of The Great Gatsby, “but I don’t think so”. If the first half of his sentence was perfunctory, the second half was the wildest kind of understatement. By that point, Fitzgerald knew what he had achieved. Six months earlier, he informed Maxwell Perkins, his editor at Scribner’s, that his work in progress “is about the best American novel ever written”. And Perkins’s reaction had done little to shake his sense of confidence. He called the book “a wonder”, adding: “As for sheer writing, it’s astonishing.”

Maybe my book is rotten,” F Scott Fitzgerald told a friend, in February 1925, shortly before the publication of The Great Gatsby, “but I don’t think so”. If the first half of his sentence was perfunctory, the second half was the wildest kind of understatement. By that point, Fitzgerald knew what he had achieved. Six months earlier, he informed Maxwell Perkins, his editor at Scribner’s, that his work in progress “is about the best American novel ever written”. And Perkins’s reaction had done little to shake his sense of confidence. He called the book “a wonder”, adding: “As for sheer writing, it’s astonishing.” What is America really fighting over in the upcoming election? Not any particular issue. Not even Democrats versus

What is America really fighting over in the upcoming election? Not any particular issue. Not even Democrats versus