Anya Ventura in The Baffler:

IN 1971, AFTER THE UNITED STATES had declared a War on Poverty but before the Wars on Drugs and Terrorism, Richard Nixon declared a War on Cancer: a battle against the bad cells that attack our bodies. Three months earlier, Lewis F. Powell, a lawyer on the board of Philip Morris and future Supreme Court justice, had written a confidential memo with lasting consequences that urged corporations to become more aggressively involved in politics in order to advance their own interests. In metaphoric terms, then, cancer was an apt disease of the times: a problem of unchecked growth, deadly and yet slow to materialize. Its elevated status was cemented over the following decades, as cancer became an economic, bodily, ecological, and spiritual question threaded through every facet of American life. It was against this backdrop, in 1975, that a merchant banker named Richard Stephenson bought up a community hospital in Zion, Illinois, a pious town along the western shore of Lake Michigan, just south of the Wisconsin state line. Eventually ballooning into a network of hospitals christened the Cancer Treatment Centers of America, it became a business catering to the most desperate—one of a boom industry’s most grotesque manifestations that in 2013 was valued roughly at $1.36 billion.

IN 1971, AFTER THE UNITED STATES had declared a War on Poverty but before the Wars on Drugs and Terrorism, Richard Nixon declared a War on Cancer: a battle against the bad cells that attack our bodies. Three months earlier, Lewis F. Powell, a lawyer on the board of Philip Morris and future Supreme Court justice, had written a confidential memo with lasting consequences that urged corporations to become more aggressively involved in politics in order to advance their own interests. In metaphoric terms, then, cancer was an apt disease of the times: a problem of unchecked growth, deadly and yet slow to materialize. Its elevated status was cemented over the following decades, as cancer became an economic, bodily, ecological, and spiritual question threaded through every facet of American life. It was against this backdrop, in 1975, that a merchant banker named Richard Stephenson bought up a community hospital in Zion, Illinois, a pious town along the western shore of Lake Michigan, just south of the Wisconsin state line. Eventually ballooning into a network of hospitals christened the Cancer Treatment Centers of America, it became a business catering to the most desperate—one of a boom industry’s most grotesque manifestations that in 2013 was valued roughly at $1.36 billion.

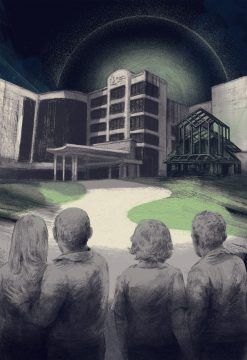

According to the company’s lore, a story I would hear recounted many times during my visits to Zion, Stephenson rebranded the Zion-Benton hospital in 1988 following the death of his mother from bladder cancer. In 1990, he acquired a second hospital in Tulsa, Oklahoma—the former City of Faith hospital that had been constructed in 1978 by Oral Roberts after he received a vision from a nine-hundred-foot-tall Jesus. In addition to Tulsa and the flagship hospital in Zion, the CTCA would go on to open more treatment centers near Philadelphia, Atlanta, and Phoenix. Their treatment model became known as the “Mother Standard” and sought to treat the whole person: mind, body, and spirit. In addition to traditional medicine—chemotherapy, radiation—the CTCA offers patients acupuncture, chiropractics, nutritional advice, naturopathy, and spiritual support. They also promote expensive, cutting-edge treatments like immunotherapy. “It’s really unbelievable how one doctor can tell me I have two months to live, and then I go the Cancer Treatment Centers of America, and they save my life,” says a woman featured in one of the CTCA’s many television advertisements, whose intertitle informs us that “You have no expiration date.” According to its slogan at the time, CTCA is “winning the fight against cancer, every day.”

When it’s not likened to a “fight,” cancer is often framed as a “journey,” a soul-fortifying pilgrimage through dangerous geography. In the opening passage of Illness as Metaphor, Susan Sontag dubbed it “the kingdom of the sick.” Christopher Hitchens called it “Tumortown;” Barbara Ehrenreich, “Cancerland.” But at the CTCA, patients are first welcomed in their journey by a concierge at what’s called “First Connections”; at the Zion hospital, a moss-colored oil portrait of Stephenson beams down from the front desk.

More here.