Natalie Angier in the New York Review of Books:

Alytes obstetricans, the common midwife toad, may be as small as a bar of hotel soap with skin as drab as leaf litter, yet its life story is, quite simply, one for the ages. The job that lends the toads their informal name is done by the male. Come breeding season, a female toad will solicit the services of a male, who mounts her from behind, gripping her torso with his front legs while angling his rear toes to stimulate her genitals. A few minutes pass, he gives her midriff a firm squeeze, and out pops the “baby”: a glistening mass of toad eggs, linked together like pearls on a string, which the male promptly fertilizes with a shot of sperm. As the female hops away—her task is through—midwife becomes nursemaid: the male carefully untangles the inseminated strands of eggs and wraps them around his body. He will carry this cargo everywhere for the next month or two, cleaning and hydrating the eggs until they’re ready to hatch. Yes, he’s a model modern father.

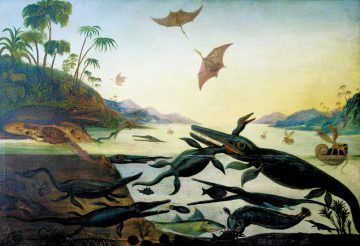

Alytes is also more European than a pack of Gauloises cigarettes. As Tim Flannery explains in Europe: A Natural History, his deeply satisfying and splendidly written survey of the geological, zoological, climatological, and biophilosophical roots of that heavyweight set of coordinates we call Europe, midwife toads are among the only animals that survive from the dawn of the European project 100 million years ago. That is when the European subcontinent, then a tropical archipelago, began to consolidate and take the shape it more or less has today, and when Europe as a biologically distinct landscape emerged.

More here.