Plumes

.

by Arash Saedinia

from Rattle #54, Winter 2016

.

by Arash Saedinia

from Rattle #54, Winter 2016

Kelly Servick in Science:

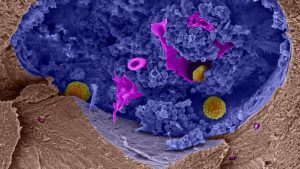

In multiple sclerosis (MS), a disease that strips away the sheaths that insulate nerve cells, the body’s immune cells come to see the nervous system as an enemy. Some drugs try to slow the disease by keeping immune cells in check, or by keeping them away from the brain. But for decades, some researchers have been exploring an alternative: wiping out those immune cells and starting over. The approach, called hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), has long been part of certain cancer treatments. A round of chemotherapy knocks out the immune system and an infusion of stem cells—either from a patient’s own blood or, in some cases, that of a donor—rebuilds it. The procedure is already in use for MS and other autoimmune diseases at several clinical centers around the world, but it has serious risks and is far from routine. Now, new results from a randomized clinical trial suggest it can be more effective than some currently approved MS drugs. “A side-by-side comparison of this magnitude had never been done,” says Paolo Muraro, a neurologist at Imperial College London who has also studied HSCT for MS. “It illustrates really the power of this treatment—the level of efficacy—in a way that’s very eloquent.”

In multiple sclerosis (MS), a disease that strips away the sheaths that insulate nerve cells, the body’s immune cells come to see the nervous system as an enemy. Some drugs try to slow the disease by keeping immune cells in check, or by keeping them away from the brain. But for decades, some researchers have been exploring an alternative: wiping out those immune cells and starting over. The approach, called hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), has long been part of certain cancer treatments. A round of chemotherapy knocks out the immune system and an infusion of stem cells—either from a patient’s own blood or, in some cases, that of a donor—rebuilds it. The procedure is already in use for MS and other autoimmune diseases at several clinical centers around the world, but it has serious risks and is far from routine. Now, new results from a randomized clinical trial suggest it can be more effective than some currently approved MS drugs. “A side-by-side comparison of this magnitude had never been done,” says Paolo Muraro, a neurologist at Imperial College London who has also studied HSCT for MS. “It illustrates really the power of this treatment—the level of efficacy—in a way that’s very eloquent.”

Nearly 30 years ago, when hematologist Richard Burt saw how HSCT worked in patients with leukemia and lymphoma, he was struck by a curious effect: After those patients rebuilt their immune systems, their childhood vaccines no longer protected them, recalls Burt, now at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Evanston, Illinois. Without a new vaccination, the new immune cells wouldn’t recognize viruses such as measles and mumps and launch a prompt counterattack. That suggested that in the case of an autoimmune disease, reseeding the immune system might help the body “forget” that its own cells were the enemy. Burt and others have since used HSCT for a variety of autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis and lupus. In the past few years, several teams have reported encouraging results in MS. But only one study—which evaluated just 17 patients—directly compared HSCT to other available drug treatments.

More here.

Andrew Gelman, Sharad Goel, and Daniel E. Ho in the Boston Review:

Just over forty years ago the Supreme Court struck down race-based quotas in school admissions while also upholding the core tenets of affirmative action. In the landmark 1978 decision, Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr., singled out Harvard’s admissions program as an exemplar for achieving diversity and applauded the university’s own description of its policy, according to which the “race of an applicant may tip the balance in his favor just as geographic origin or a life spent on a farm may tip the balance in other candidates’ cases.” As the Supreme Court would later emphasize, such review considered race merely a “factor of a factor of a factor.”

Just over forty years ago the Supreme Court struck down race-based quotas in school admissions while also upholding the core tenets of affirmative action. In the landmark 1978 decision, Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr., singled out Harvard’s admissions program as an exemplar for achieving diversity and applauded the university’s own description of its policy, according to which the “race of an applicant may tip the balance in his favor just as geographic origin or a life spent on a farm may tip the balance in other candidates’ cases.” As the Supreme Court would later emphasize, such review considered race merely a “factor of a factor of a factor.”

Harvard’s policy is now being challenged in federal district court in a suit that could reshape the role of race in college admissions.

In past efforts to dismantle affirmative action—from Bakke to, most recently, a case brought by two white women against the University of Texas—the plaintiffs have alleged that race-conscious admissions policies hurt white applicants. But courts have consistently held that race may be employed to achieve the educational gains that stem from a diverse student body when considered “holistically,” as one among many factors. The latest legal salvo takes a different, and potentially more potent, tack. The litigants argue that Harvard, in its quest for racial diversity, unjustly penalizes a minority group: Asian Americans.

More here.

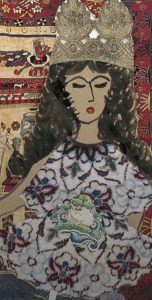

Roya Hakakian in Tablet:

Among the world’s endangered minorities, Iranian Jews are an anomaly. Like their counterparts, their conditions categorically refute all the efforts their nation makes at seeming civilized and egalitarian—and so they embody, often without wanting to, all that is ugly and unjust about their native land.

Among the world’s endangered minorities, Iranian Jews are an anomaly. Like their counterparts, their conditions categorically refute all the efforts their nation makes at seeming civilized and egalitarian—and so they embody, often without wanting to, all that is ugly and unjust about their native land.

But Iran’s Jewish community does something more. It also embodies the nation’s hope, the narrative of its resistance and struggle for a better future—one that has been on the brink of arriving ever since the revolution in 1979. To understand why Jews continue to remain in Iran is to understand the tortured tale of Iran. Nowhere else can the stubborn continuity of a minority stand as a metaphor in the elegy of a nation’s downfall.

The metaphor is apt because it is born out of a paradox. And contemporary Iran is nothing if not an enigmatic paradox. The world’s only Shiite theocracy—the archenemy of Israel—led by Holocaust deniers, is still home to some 10,000 Jews. Time and again, leading journalists have used this fact to make a partisan point. They have gone into synagogues, sat across from one of the few savvy representatives of the community, and asked the same tired questions: Are you afraid? Are you mistreated? Do you like Israel? Only to return to broadcast the same tired answers: We are not afraid. We are treated very well. We only pray to Jerusalem, but belong to Iran.

More here.

Ian Walker in The New European:

Rosa Luxemburg thought Berlin could hide her. Five days into 1919, the Marxist revolutionary had helped to transform a wave of strikes and protests in the city into open revolution – the so-called Spartacist uprising. But by January 12, she was on the run, the revolt crushed by right-wing militia groups deployed by Germany’s new socialist government.

Rosa Luxemburg thought Berlin could hide her. Five days into 1919, the Marxist revolutionary had helped to transform a wave of strikes and protests in the city into open revolution – the so-called Spartacist uprising. But by January 12, she was on the run, the revolt crushed by right-wing militia groups deployed by Germany’s new socialist government.

However, all was not lost. Berlin, in those febrile post-war months, still offered hope to her. It was a city filled with revolutionaries, fellow travellers and sympathetic soldiers, factory workers and intellectuals. In other words, there were plenty of hotel rooms, basements, offices and attics in which a Marxist fugitive could lie low, regroup and work out what to do next.

But it turned out that the city couldn’t hide her. Berlin was also full of volunteers and spies working on behalf of the government. Then there were those militia groups – the Freikorps, the hastily-assembled units of soldiers returning from the front who were happy to do the government’s counter-revolutionary killing. Finally, there were Berlin’s perennial gossips, informers and trouble-makers.

In the event, Luxemburg lasted just three days as an outlaw.

More here.

Amber A’Lee Frost at The Baffler:

And even if we could get a President Gillibrand in 2020, another lukewarm Democratic presidency will not only further impoverish and destabilize the working class and its suffering institutions, it will also all but guarantee that 2024 brings us POTUS Hamburglar in an SS uniform. No, it’s Bernie or bust. I don’t care if we have to roll him out on a hand truck and sprinkle cocaine into his coleslaw before every speech. If he dies mid-run, we’ll stuff him full of sawdust, shove a hand up his ass, and operate him like a goddamn muppet.

And even if we could get a President Gillibrand in 2020, another lukewarm Democratic presidency will not only further impoverish and destabilize the working class and its suffering institutions, it will also all but guarantee that 2024 brings us POTUS Hamburglar in an SS uniform. No, it’s Bernie or bust. I don’t care if we have to roll him out on a hand truck and sprinkle cocaine into his coleslaw before every speech. If he dies mid-run, we’ll stuff him full of sawdust, shove a hand up his ass, and operate him like a goddamn muppet.

So, if you believe in class politics, don’t pull an Owen Jones. You remember Owen. He went rogue and demanded the resignation of his country’s most inspiring and promising socialist politician, you know, for “pragmatic” reasons. I don’t know why he did it, but I have my suspicions as to why a lot of people who should know better are doing much the same right now. I suspect it has something to do with caution, or at least the professional credibility a writer gains by appearing to heed such caution.

more here.

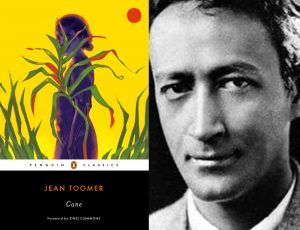

Ismail Muhammad at the Paris Review:

The literary world was then (as it is now, perhaps) hungry for representative black voices; as Hutchinson writes, “Many stressed the ‘authenticity’ of Toomer’s African-Americans and the lyrical voice with which he conjured them into being.” This act of conjuring lured critics into reflexively accepting the book as a representation of the black South—and Toomer as the voice of that South. As his one-time friend Waldo Frank remarked in a forward to the book’s original edition, “This book is the South.” Cane transformed Toomer into a Negro literary star whose influence would filter down through African-American literary history: his interest in the folk tradition crystallized the Harlem Renaissance’s search for a useable Negro past, and would be instructive for later writers from Zora Neale Hurston to Ralph Ellison to Elizabeth Alexander.

The literary world was then (as it is now, perhaps) hungry for representative black voices; as Hutchinson writes, “Many stressed the ‘authenticity’ of Toomer’s African-Americans and the lyrical voice with which he conjured them into being.” This act of conjuring lured critics into reflexively accepting the book as a representation of the black South—and Toomer as the voice of that South. As his one-time friend Waldo Frank remarked in a forward to the book’s original edition, “This book is the South.” Cane transformed Toomer into a Negro literary star whose influence would filter down through African-American literary history: his interest in the folk tradition crystallized the Harlem Renaissance’s search for a useable Negro past, and would be instructive for later writers from Zora Neale Hurston to Ralph Ellison to Elizabeth Alexander.

For Toomer, however, this close identification with black folk culture, and the Negro in general, was inimical to his own self-conception. He largely attempted to evade conventional modes of racial identification. As he pursued a career as a writer, the young artist began to articulate an idiosyncratic and highly individualistic notion of race wherein he was “American, neither black nor white, rejecting these divisions, accepting people as people.”

more here.

Seamus Perry at the LRB:

It is not the critical fashion to dwell on Shelley’s Platonism, and it is true that his expressions of enthusiasm for various Platonic doctrines were qualified. But it is difficult not to see the main feeling in his work as a conviction that the world of experience is merely an imperfect clue to the real reality that lies beyond, the idea of which haunts it; and, after all, that is nothing but a Platonic notion. ‘The truth and splendour of his imagery and the melody of his language is the most intense that it is possible to conceive,’ Shelley says of Plato in his polemic A Defence of Poetry; he translated the Symposium, and once said he would rather be damned with Plato and Bacon than go to heaven with the Anglican worthies Paley and Malthus. ‘You know that I always seek in what I see the manifestation of something beyond the present & tangible object,’ he told a correspondent: there is ‘no more fitting epigraph to the dynamic driving Shelley’s literary career’, according to the poet and critic Michael O’Neill, one of our best Shelleyan commentators. The ghostly effects that this penchant for intangibility enables in his poetry – its distinctive repertoire of veils and shadows and hauntings – are eerily magnificent and inimitably his own. No other poet could have conceived the extraordinary opening lines of the ‘Hymn to Intellectual Beauty’: ‘The awful shadow of some unseen Power/Floats though unseen amongst us’. Not even a Power, but the shadow of a Power, so already placed at two removes from anything like concrete presence; and then the oddly effective insistence involved in repeating the word ‘unseen’, as though he were struggling to capture the Power’s sheerly counter-empirical invisibility by doubling up the word.

It is not the critical fashion to dwell on Shelley’s Platonism, and it is true that his expressions of enthusiasm for various Platonic doctrines were qualified. But it is difficult not to see the main feeling in his work as a conviction that the world of experience is merely an imperfect clue to the real reality that lies beyond, the idea of which haunts it; and, after all, that is nothing but a Platonic notion. ‘The truth and splendour of his imagery and the melody of his language is the most intense that it is possible to conceive,’ Shelley says of Plato in his polemic A Defence of Poetry; he translated the Symposium, and once said he would rather be damned with Plato and Bacon than go to heaven with the Anglican worthies Paley and Malthus. ‘You know that I always seek in what I see the manifestation of something beyond the present & tangible object,’ he told a correspondent: there is ‘no more fitting epigraph to the dynamic driving Shelley’s literary career’, according to the poet and critic Michael O’Neill, one of our best Shelleyan commentators. The ghostly effects that this penchant for intangibility enables in his poetry – its distinctive repertoire of veils and shadows and hauntings – are eerily magnificent and inimitably his own. No other poet could have conceived the extraordinary opening lines of the ‘Hymn to Intellectual Beauty’: ‘The awful shadow of some unseen Power/Floats though unseen amongst us’. Not even a Power, but the shadow of a Power, so already placed at two removes from anything like concrete presence; and then the oddly effective insistence involved in repeating the word ‘unseen’, as though he were struggling to capture the Power’s sheerly counter-empirical invisibility by doubling up the word.

more here.

Charles Derber and Yale Magrass in AlterNet:

On October 1, 2014, the National Labor Relations Board ruled that a Burger King franchise in Ferndale, Michigan, near Detroit, had bullied a part-time worker, Claudette Wilson, by sending her home two hours early for not positioning pickles correctly on her burgers. As Judge Arthur J. Anchan put it, the company illegally sent Wilson home for failing to “put pickles on her sandwiches in perfect squares.”

On October 1, 2014, the National Labor Relations Board ruled that a Burger King franchise in Ferndale, Michigan, near Detroit, had bullied a part-time worker, Claudette Wilson, by sending her home two hours early for not positioning pickles correctly on her burgers. As Judge Arthur J. Anchan put it, the company illegally sent Wilson home for failing to “put pickles on her sandwiches in perfect squares.”

Such absurd but intimidating and humiliating bullying of a very low-paid worker was retaliation aimed at intimidating Wilson from continuing her efforts to organize low-wage Burger King workers. A few days earlier, she had stopped at the store to ask workers coming off their shifts to fill out a questionnaire about their wages. A manager had written her up for violating the store’s “loitering and solicitation” policy, something that Judge Anchan also said was “protected activity” and thus illegal. Wilson said she had not done the pickles quite perfectly because of her anger about the earlier unfair treatment. The story gets bigger because Wilson was one of several workers, including Romell Frazier, who were members of a group called D15, part of the Fast Food Forward Network trying to unionize Michigan Burger Kings. Wilson’s “pickle problem” was really part of a larger and more serious pickle faced by the workers. The Michigan Burger King franchisee was systematically going after workers who were part of D15 and threatening them with sanctions, including firing.

More here.

We’re skeet shooting

the potter’s seconds.

The catapult slings

warped plates, cracked

vases in erratic arcs

across the dry creek canyon.

Each Thursday evening

we obliterate

the week’s mistakes.

When the pellet-spread connects,

explodes a shrapnel star

it’s an absolution.

Lucinda’s been casting

reproductions of Egyptian

bowls with tiny feet.

One seems near perfect,

but when I set it

on the trap-box edge

it lists, daylight gleaming

beneath the toes of one foot.

When wet and forming

it must have rested

on a warp, something

not quite level in the firing.

It seems somehow unfair

this small, lame thing

wound up in the slag-box

destined for buckshot

just because it totters.

And it strikes me

how much easier it is

to love a flawed object—

the supplicant’s posture

like a pair of cupped hands,

the sloped bowl tilted in offering,

its little feet of clay.

by Caron Andregg

from Rattle Magazine, #16, 2001

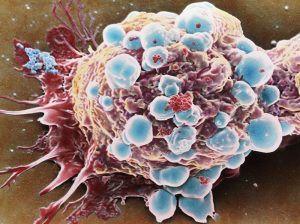

Heidi Ledford in Nature:

A survey of thousands of advanced cancers suggests a way to identify those most likely to respond to revolutionary therapies that unleash an immune response against tumours. But the results highlight how difficult it will be to translate such an approach into a reliable clinical test. The findings1, published on 14 January in Nature Genetics, are the latest line of evidence to suggest that tumours with a large number of DNA mutations are more likely to respond to immunotherapies than are cancers with fewer mutations — and result in longer survival for people who receive treatment. Researchers have long sought a way to select the people — generally a minority of patients — who are most likely to respond to immunotherapies and to spare others from the treatments’ side effects, which can include kidney failure and lung problems.

A survey of thousands of advanced cancers suggests a way to identify those most likely to respond to revolutionary therapies that unleash an immune response against tumours. But the results highlight how difficult it will be to translate such an approach into a reliable clinical test. The findings1, published on 14 January in Nature Genetics, are the latest line of evidence to suggest that tumours with a large number of DNA mutations are more likely to respond to immunotherapies than are cancers with fewer mutations — and result in longer survival for people who receive treatment. Researchers have long sought a way to select the people — generally a minority of patients — who are most likely to respond to immunotherapies and to spare others from the treatments’ side effects, which can include kidney failure and lung problems.

But the immune system is complicated, and it has proved difficult to determine what makes one tumour vulnerable to treatment but allows another to escape unscathed. “The essence of pharmaceutical development is to try and find meaningful but relatively simple guideposts, which is often in defiance of the way that biology works,” says Chris Shibutani, a biotechnology analyst at the investment bank Cowen, in Boston, Massachusetts. One hypothesis is that the more genetically different a tumour is from normal tissue, the more likely it is that the immune system will recognize and eliminate it.

More here.

by Holly A. Case

There is a nice neighborhood in Istanbul called Kadıköy, which means “village of the kadı,” or “judge.” One might as well call it Kediköy, however: “village of the cat.” There are a lot of stray cats there, as there are throughout the city. Once I saw a poster with a photo of a cat that said “Lost” at the bottom, then a phone number (rather like seeing a sign on the beach with a picture of a shell reading “Lost,” then a phone number). The sign was taped to a utility box on the street. On top of the box was a stray cat, lounging. It looked a lot like the one in the photo.

A few years ago, I met a retired architect who came down to the promenade along the reinforced shoreline every morning to feed the stray cats. “If there is a heaven and hell, which I don’t believe there is, but if there is, I will go to heaven on their prayers,” he told me.

In a different part of the city, my friend Kerim—a tailor—begins his two-hour commute to work at 6 a.m. Six days a week he pets the stray dogs on one side of the highway, then crosses to the other side to catch the bus where he meets a second pack of strays and pets them. Recently he constructed a luxury home for a stray cat who had taken up residence at the bus stop. It’s a cardboard box wrapped in plastic (to keep it dry), with a styrofoam roof (for insulation), a bubble-wrap subfloor (also for insulation), cardboard flooring, and an interior wall-to-wall rag (for extra comfort). He proudly showed me a photo of it with the occupant just visible inside. Read more »

In all cases, the goal is to move past literal life into the imagination

to render the almost—to express the mysterious ambiguity that is. . .

……………………………………………….. —Nicholas Dawidoff, writer

yesterday

I walked our yard

with a grandson

who toddled beside

in a state

almost

of disequilibrium

but he tended

his balance

and stayed upright

and the walk

we walked was

almost

something which would come again

when he’d walk with

his grandson —if his days

were almost

like mine

almost as lucky

restless

reckless

full

fettered

free

almost

happy as a calm

shifty sea

full and vacant as the hole

at the center of a wheel

around which

if it were not hollow

its rim would never spin

and there’d be nothing,

including me

but nada is nothing

we can imagine

or almost

be

Jim Culleny

5/22/17

by Emrys Westacott

Like millions of other people in the US, I often begin the day by listening to ‘Morning Edition,’ the early morning news program on National Public Radio. Sometimes, though, I get so disgusted by the rubbish spewed by the politicians being interviewed, or so infuriated by the flimsiness of the questions put to them, that I just can’t stand it and have to take myself out of earshot. Friday was a case in point.

Like millions of other people in the US, I often begin the day by listening to ‘Morning Edition,’ the early morning news program on National Public Radio. Sometimes, though, I get so disgusted by the rubbish spewed by the politicians being interviewed, or so infuriated by the flimsiness of the questions put to them, that I just can’t stand it and have to take myself out of earshot. Friday was a case in point.

The topic, of course, was the partial shutdown of the federal government. Congressman Gary Palmer, a Republican from Alabama, came on to be interviewed. Here was the first question

“Both sides have to give in any kind of compromise deal… Where should the Republicans and the president be willing to compromise?”

Right there was where I’d had enough. It is simply nonsense that in every negotiation both sides have to compromise, moving toward some sort of shared middle ground. This is not the received wisdom when it comes to dealing with hostage takers. And that is exactly the situation the House of Representatives is currently in. Read more »

by Shawn Crawford

(The following is an excerpt from Crawford’s lecture at the Lausanne, Switzerland conference of The Society of Data Analysts Committed to Reducing Any Complexity to a Single Sobering Graph. Researchers will remember the group’s acrimonious split from the Social Scientists United for Reducing Any Cultural Crisis to a Single Meme. In a classic dispute among the “hard” and “soft” sciences, the two sides exchanged a dizzying array of pie charts and Willie Wonka images with devastating captions to no avail.)

. . . I want to thank Professor Owens once again for his electrifying lecture on determining the outcome of any baseball season by crunching the data from a ten-game sample, reducing the number of games played by 152. Like so much breakthrough research, this also produced an unintended benefit: the freeing up of nearly 10,000 extra hours on TBS for reruns of The Big Bang Theory. I know we are all grateful.

. . . I want to thank Professor Owens once again for his electrifying lecture on determining the outcome of any baseball season by crunching the data from a ten-game sample, reducing the number of games played by 152. Like so much breakthrough research, this also produced an unintended benefit: the freeing up of nearly 10,000 extra hours on TBS for reruns of The Big Bang Theory. I know we are all grateful.

I still remember Professor Owens bursting onto to the scene when his algorithm, pushing the Sunway TaihuLight supercomputer to its limits, proved conclusively that Dewey had indeed defeated Truman. While his subsequent modeling has produced dozens of legislative fixes for this mathematical reality, we know the current gridlock in Washington continues to thwart his efforts.

When Dr. Harry Lutz from DataTorrent approached me about joining him on the cutting edge of the Sober Graphing movement, I knew I couldn’t say no. While Thomas Piketty appeared to be rapidly consolidating the research space in Sober Graphing, I reckoned Dr. Lutz had a clear edge moving forward: his proprietary Sober Index, able to finally tackle such vexing questions as does the bar graph illustrating the concentration of wealth since World War II achieve Peak Soberness as it relates to income inequality? Using a baseline of soberness, the realization of just how worthless a degree in the humanities will be, Dr. Lutz built out his Soberness Index with enviable precision.

But would Sober Graphing prove as chimerical as Shocking Graphing and Surprising Graphing in offering real advances? The number of graphs required in these areas had also become problematic: if it’s going to take three scatters, a 2-D pie, and a funnel graph to shock me, perhaps we need to revisit the biases lurking in our data field.

Lutz and I became convinced the Sober Index could help us express the answer to any seemingly intractable question in one elegant, sobering graph. Furthermore, we posited the level of soberness, correctly calibrated to the industry or society addressed, could effect lasting and measurable change. But before we tackled broader issues, we decided to test our hypothesis on a basic level: could the essence of my existence be explained in One Sobering Graph, or OSG, now the recognized nomenclature? Read more »

by Tamuira Reid

I met Arnie at a Cocaine Anonymous meeting the year before I got sober for the first time. I was high as fuck, eyes lit and hands fidgeting in my lap, then my jacket pockets, then my lap again. Maybe I thought being in a room full of non-high people would help even my scorecard with God. I had a lot of interesting thoughts back then, but I was usually smart enough to keep them to myself.

Arnie was wearing a neon orange trucker hat with the word “Grandma” scrawled above the brim in what looked like sharpie. His long, sixty-something body stretched out from beneath a threadbare track suit, and his sneakers were both untied. I remember being distracted by this, the laces calling my name, Tamuira, Tamuira! Come tie me! I would later learn, over our decade of friendship, that he was claustrophobic, and his feet needed so be able to “breathe better”.

And this was what I found most comforting about about Arnie; his weirdness, his eccentricities. He didn’t need drugs to take him into an altered state because he was already in one.

“Wanna get coffee?”

I rolled my eyes and lifted up my Styrofoam cup, thinking he was just another gross old-timer in the program, picking-up on a newbie.

“I have a sponsor already.”

“I’m not hitting on you, honey. I’m gay,” he said, grabbing a cookie off the table and breaking it in half. “Straight guys don’t do neon.”

“I’m not really sober right now,” I confided. Partly to get rid of him, partly to ease my guilty conscious.

“I can tell. Your jaw is like a goddamn meat grinder.” Read more »

by Samia Altaf

In October of 2014, a bunch of young men and women did their university proud. A couple of engineers, two finance graduates, a biology major, some finishing accounting and business degrees, and a clutch from the school of humanities and social sciences; Muslims mostly, two Christians, a lone Hindu, one Buddhist wannabe, and two oblivious to religion though aware of its place in other folks’ lives. They came together from Sahiwal, Karachi, Gilgit, Swat, Peshawar, Gujranwala, one from Quetta (non-Baluchi), and two from Delhi via the University of Texas. Though the majority of students and faculty stayed away, these young men and women with similar features and skin tones, in colorful flowing kurtas, chooridars, skinny jeans, funky T-shirts, and hijabs, got together to celebrate Diwali, a festival that celebrates Ram’s return from exile.

In October of 2014, a bunch of young men and women did their university proud. A couple of engineers, two finance graduates, a biology major, some finishing accounting and business degrees, and a clutch from the school of humanities and social sciences; Muslims mostly, two Christians, a lone Hindu, one Buddhist wannabe, and two oblivious to religion though aware of its place in other folks’ lives. They came together from Sahiwal, Karachi, Gilgit, Swat, Peshawar, Gujranwala, one from Quetta (non-Baluchi), and two from Delhi via the University of Texas. Though the majority of students and faculty stayed away, these young men and women with similar features and skin tones, in colorful flowing kurtas, chooridars, skinny jeans, funky T-shirts, and hijabs, got together to celebrate Diwali, a festival that celebrates Ram’s return from exile.

Diwali, along with Holi, if not officially banned, have been marginalized in Pakistan as “Hindu” festivals although in the multi-religious society of the colonial period they were celebrated with as much enthusiasm as Eid and Christmas. The largest Diwali celebration in Lahore was held at the famous Laxmi Chowk, home to the Laxmi building, a marvel of Indo-European architecture and once the throbbing heart of the local film industry. All citizens, men, women, children, Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, Christians, and Parsis gathered to celebrate the return of Ram to Ayodhya at Chowk with the adjoining building lit bright with lamps.

Almost seventy years on, these young people united in defiance to mark this heritage of their plural past. Ignoring looks of puzzlement and disapproval, they lighted the little lamps—diyas—fired with mustard oil as in the past, each lighted lovingly, one at a time, coaxing the hand-rolled cotton wick to sputter and then hold its own—quite like the event—knowing in their hearts that nurturing the flame symbolized a larger, more tenuous, goal. So they celebrated Diwali, and, I suppose, their own lives for the evening was mellow and they are young and alive and still hopeful. (Wordsworth: what a joy it was to be alive). They shared Mithai, music, poetry, thoughts, laughter, tears, and hopes and dreams for this land and its people wondering about their own place in it. They worried about the shape of tomorrow’s world and asked what they could do to make it better. It was a celebration of hope and harmony arrayed against a background of doom and despair—would there really be a return from the long exile? Read more »

by Brooks Riley