Month: July 2018

A new look inside Theranos’s dysfunctional corporate culture

John Carreyrou in Wired:

ALAN BEAM WAS sitting in his office reviewing lab reports when Theranos CEO and founder Elizabeth Holmes poked her head in and asked him to follow her. She wanted to show him something. They stepped outside the lab into an area of open office space where other employees had gathered. At her signal, a technician pricked a volunteer’s finger, then applied a transparent plastic implement shaped like a miniature rocket to the blood oozing from it. This was the Theranos sample collection device. Its tip collected the blood and transferred it to two little engines at the rocket’s base. The engines weren’t really engines: They were nanotainers. To complete the transfer, you pushed the nanotainers into the belly of the plastic rocket like a plunger. The movement created a vacuum that sucked the blood into them. Or at least that was the idea. But in this instance, things didn’t go quite as planned. When the technician pushed the tiny twin tubes into the device, there was a loud pop and blood splattered everywhere. One of the nanotainers had just exploded. Holmes looked unfazed. “OK, let’s try that again,” she said calmly. Beam1 wasn’t sure what to make of the scene. He’d only been working at Theranos, the Silicon Valley company that promised to offer fast, cheap blood tests from a single drop of blood, for a few weeks and was still trying to get his bearings.

ALAN BEAM WAS sitting in his office reviewing lab reports when Theranos CEO and founder Elizabeth Holmes poked her head in and asked him to follow her. She wanted to show him something. They stepped outside the lab into an area of open office space where other employees had gathered. At her signal, a technician pricked a volunteer’s finger, then applied a transparent plastic implement shaped like a miniature rocket to the blood oozing from it. This was the Theranos sample collection device. Its tip collected the blood and transferred it to two little engines at the rocket’s base. The engines weren’t really engines: They were nanotainers. To complete the transfer, you pushed the nanotainers into the belly of the plastic rocket like a plunger. The movement created a vacuum that sucked the blood into them. Or at least that was the idea. But in this instance, things didn’t go quite as planned. When the technician pushed the tiny twin tubes into the device, there was a loud pop and blood splattered everywhere. One of the nanotainers had just exploded. Holmes looked unfazed. “OK, let’s try that again,” she said calmly. Beam1 wasn’t sure what to make of the scene. He’d only been working at Theranos, the Silicon Valley company that promised to offer fast, cheap blood tests from a single drop of blood, for a few weeks and was still trying to get his bearings.

He knew the nanotainer was part of the company’s proprietary blood-testing system, but he’d never seen one in action before. He hoped this was just a small mishap that didn’t portend bigger problems. The lanky pathologist’s circuitous route to Silicon Valley had started in South Africa, where he grew up. After majoring in English at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg (“Wits” to South Africans), he’d moved to the United States to take premed classes at Columbia University in New York City. The choice was guided by his conservative Jewish parents, who considered only a few professions acceptable for their son: law, business, and medicine.

More here.

How Identity Politics Is Harming the Sciences

Heather MacDonald in City Journal:

Identity politics has engulfed the humanities and social sciences on American campuses; now it is taking over the hard sciences. The STEM fields—science, technology, engineering, and math—are under attack for being insufficiently “diverse.” The pressure to increase the representation of females, blacks, and Hispanics comes from the federal government, university administrators, and scientific societies themselves. That pressure is changing how science is taught and how scientific qualifications are evaluated. The results will be disastrous for scientific innovation and for American competitiveness. A scientist at UCLA reports: “All across the country the big question now in STEM is: how can we promote more women and minorities by ‘changing’ (i.e., lowering) the requirements we had previously set for graduate level study?” Mathematical problem-solving is being deemphasized in favor of more qualitative group projects; the pace of undergraduate physics education is being slowed down so that no one gets left behind.

Identity politics has engulfed the humanities and social sciences on American campuses; now it is taking over the hard sciences. The STEM fields—science, technology, engineering, and math—are under attack for being insufficiently “diverse.” The pressure to increase the representation of females, blacks, and Hispanics comes from the federal government, university administrators, and scientific societies themselves. That pressure is changing how science is taught and how scientific qualifications are evaluated. The results will be disastrous for scientific innovation and for American competitiveness. A scientist at UCLA reports: “All across the country the big question now in STEM is: how can we promote more women and minorities by ‘changing’ (i.e., lowering) the requirements we had previously set for graduate level study?” Mathematical problem-solving is being deemphasized in favor of more qualitative group projects; the pace of undergraduate physics education is being slowed down so that no one gets left behind.

The National Science Foundation (NSF), a federal agency that funds university research, is consumed by diversity ideology. Progress in science, it argues, requires a “diverse STEM workforce.” Programs to boost diversity in STEM pour forth from its coffers in wild abundance. The NSF jump-started the implicit-bias industry in the 1990s by underwriting the development of the implicit association test (IAT). (The IAT purports to reveal a subject’s unconscious biases by measuring the speed with which he associates minority faces with positive or negative words; see “Are We All Unconscious Racists?,” Autumn 2017.) Since then, the NSF has continued to dump millions of dollars into implicit-bias activism. In July 2017, it awarded $1 million to the University of New Hampshire and two other institutions to develop a “bias-awareness intervention tool.” Another $2 million that same month went to the Department of Aerospace Engineering at Texas A&M University to “remediate microaggressions and implicit biases” in engineering classrooms.

The tortuously named “Inclusion across the Nation of Communities of Learners of Underrepresented Discoverers in Engineering and Science” (INCLUDES) bankrolls “fundamental research in the science of broadening participation.” There is no such “science,” just an enormous expenditure of resources that ducks the fundamental problems of basic skills and attitudes toward academic achievement.

More here.

What Religion Gives Us (That Science Can’t)

Stephen Asma in the New York Times:

It’s a tough time to defend religion. Respect for it has diminished in almost every corner of modern life — not just among atheists and intellectuals, but among the wider public, too. And the next generation of young people looks likely to be the most religiously unaffiliated demographic in recent memory.

It’s a tough time to defend religion. Respect for it has diminished in almost every corner of modern life — not just among atheists and intellectuals, but among the wider public, too. And the next generation of young people looks likely to be the most religiously unaffiliated demographic in recent memory.

There are good reasons for this discontent: continued revelations of abuse by priests and clerics, jihad campaigns against “infidels” and homegrown Christian hostility toward diversity and secular culture. This convergence of bad behavior and bad press has led many to echo the evolutionary biologist E. O. Wilson’s claim that “for the sake of human progress, the best thing we could possibly do would be to diminish, to the point of eliminating, religious faiths.”

Despite the very real problems with religion — and my own historical skepticism toward it — I don’t subscribe to that view. I would like to argue here, in fact, that we still need religion. Perhaps a story is a good way to begin.

One day, after pompously lecturing a class of undergraduates about the incoherence of monotheism, I was approached by a shy student. He nervously stuttered through a heartbreaking story, one that slowly unraveled my own convictions and assumptions about religion.

More here.

Chipped rocks found in western China indicate that human ancestors ventured from Africa earlier than previously believed

Carl Zimmer in the New York Times:

The oldest stone tools outside Africa have been discovered in western China, scientists reported on Wednesday. Made by ancient members of the human lineage, called hominins, the chipped rocks are estimated to be as much as 2.1 million years old.

The oldest stone tools outside Africa have been discovered in western China, scientists reported on Wednesday. Made by ancient members of the human lineage, called hominins, the chipped rocks are estimated to be as much as 2.1 million years old.

The find may add a new chapter to the story of hominin evolution, suggesting that some of these species left Africa far earlier than once believed and managed to travel over 8,000 miles east of their evolutionary birthplace.

The age of the Chinese tools suggests that the hominins who made them were neither tall nor big-brained. Instead, they may have been small bipedal apes, with brains about the size of a chimpanzee’s.

“The implications of all this are large,” said Michael Petraglia, a paleoanthropologist at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, who was not involved in the new study. “We must re-evaluate our understanding of human prehistory in Eurasia.”

More here.

What Happens if the Gender Gap Becomes a Gender Chasm?

Thomas B. Edsall in the New York Times:

For nearly 40 years, the gender gap in voting has been the subject of continued speculation. How much does it matter? Would it be wide enough to put Democrats in office? Now, with President Trump ascendant, the question becomes still more urgent: What happens if the gender gap becomes a gender chasm?

For nearly 40 years, the gender gap in voting has been the subject of continued speculation. How much does it matter? Would it be wide enough to put Democrats in office? Now, with President Trump ascendant, the question becomes still more urgent: What happens if the gender gap becomes a gender chasm?

On July 7, CNN predicted that the 2018 election would “have the largest gender gap on record for a midterm election since 1958.” On the same day, Dan Balz, my former colleague at The Washington Post, wrote:

The disconnect between President Trump and female voters is serious and not getting better. That’s a potentially big problem for Republicans in the November elections.

Polling data this year clearly suggests that women are moving away from the Republican Party.

The potential gender gap in congressional voting has risen from 20 and 22 points in 2014 and 2016, according to exit polls, to 33 points in a Quinnipiac Poll published earlier this month. Men of all races say they intend to vote for Republican House candidates 50-42, while women of all races say they intend to vote for Democratic candidates 58-33.

More here.

The Enlightenment’s Cynical Critics

Katie Kelaidis in Quillette:

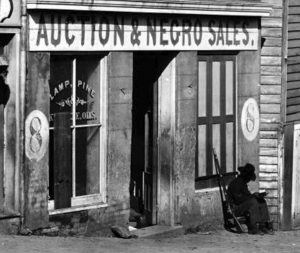

Tribalism and slavery are as old as humanity. The very first human records are records of human bondage. Reports estimate that today 60 million people are held as slaves. While each one of these lives represents an unacceptable tragedy, not one occurs with the approval of law. And that is revolutionary. For while slavery is as old as humanity, abolitionism is a relatively recent phenomenon that did not emerge until the ideas and ideals of the Enlightenment nurtured it into existence.

Tribalism and slavery are as old as humanity. The very first human records are records of human bondage. Reports estimate that today 60 million people are held as slaves. While each one of these lives represents an unacceptable tragedy, not one occurs with the approval of law. And that is revolutionary. For while slavery is as old as humanity, abolitionism is a relatively recent phenomenon that did not emerge until the ideas and ideals of the Enlightenment nurtured it into existence.

In a June 5 article for Slate, Jamelle Bouie writes of the Enlightenment: “At its heart, the movement contained a paradox: Ideas of human freedom and individual rights took root in nations that held other human beings in bondage and were then in the process of exterminating native populations.” In the context of an article largely aimed at undermining a “handful of centrist and conservative writers” who have taken up the Enlightenment’s defence, this appears to be a damning indictment of hypocrisy. That is, of course, unless one considers that, until the Enlightenment, it is nearly impossible to find a human society that did not, at least at times, practice slavery and engage in barbarous acts of conquest and colonization. It is even more difficult to find a society not engaged in these practices that reached a level of wealth and stability sufficient to allow non-survival related activities like political philosophy to flourish. The emergence of the kind of prosperous, moral societies that both Bouie and I wish to see flourish only came into existence with the moral and ethical revolution brought about by the Enlightenment.

While Bouie is correct that some Enlightenment thinkers, including Locke and Kant, did indeed advance theories of scientific racism that have had harmful consequences, he is wrong to argue that it was Enlightenment thinkers who invented scientific racism.

More here.

Saturday Qawwali Special: Subhan Ahmed Nizami & Brothers sing “Uski Hasrat Hai” by Ameer Minai

‘The Recovering’ by Leslie Jamison

Fiona Wright at The Sydney Review of Books:

The Recovering is interested in resonance, or in what Jamison calls the ‘chorus’ – other voices, other narratives of both illness and recovery – and what they might offer to other people suffering or in pain. Resonance, she insists, isn’t ‘the same as conflation’ and doesn’t ‘mean pretending we’[ve] all lived the same thing.’ It’s not about ‘perfect correspondence’ but about ‘the possibility of company’, about fellowship, perhaps, or the realisation that our experiences are so often shared, that they aren’t ever unique, and that it’s precisely this commonality that makes them important. ‘Every addiction,’ she writes, ‘lives at the intersection between public and private experience.’ So too, perhaps, every illness, every bodily injury, everything that changes the way in which we are in the world.

The Recovering is interested in resonance, or in what Jamison calls the ‘chorus’ – other voices, other narratives of both illness and recovery – and what they might offer to other people suffering or in pain. Resonance, she insists, isn’t ‘the same as conflation’ and doesn’t ‘mean pretending we’[ve] all lived the same thing.’ It’s not about ‘perfect correspondence’ but about ‘the possibility of company’, about fellowship, perhaps, or the realisation that our experiences are so often shared, that they aren’t ever unique, and that it’s precisely this commonality that makes them important. ‘Every addiction,’ she writes, ‘lives at the intersection between public and private experience.’ So too, perhaps, every illness, every bodily injury, everything that changes the way in which we are in the world.

In a way, then, this book is very much a continuation of the work of Jamison’s 2014 collection of essays The Empathy Exams, a book which was incredibly important to me while I was writing about my illness for the first time.

more here.

Richard Powers’s ‘The Overstory’

Daniel Green at The Quarterly Conversation:

The Overstory displays some of the formal and stylistic ingenuity we have come to expect from a Richard Powers novel, from his acoustically adventurous prose to his multiple, intertwined narratives (even more multiple in this novel), so characterizing it as purely “agitprop” would be neither fair nor accurate, although the novel is certainly transparent enough in its effort to promote environmental mindfulness. And since Powers has always been willing to take on the weightiest of subjects, generally treated in an earnestly sincere manner, it would go too far to call The Overstory sentimental, although the passages invoking its characters’ often rapturous appreciation of the trees that threaten to replace the characters themselves as the novel’s true dramatis personae are surely full of passionate intensity.

The Overstory displays some of the formal and stylistic ingenuity we have come to expect from a Richard Powers novel, from his acoustically adventurous prose to his multiple, intertwined narratives (even more multiple in this novel), so characterizing it as purely “agitprop” would be neither fair nor accurate, although the novel is certainly transparent enough in its effort to promote environmental mindfulness. And since Powers has always been willing to take on the weightiest of subjects, generally treated in an earnestly sincere manner, it would go too far to call The Overstory sentimental, although the passages invoking its characters’ often rapturous appreciation of the trees that threaten to replace the characters themselves as the novel’s true dramatis personae are surely full of passionate intensity.

more here.

Adam Smith: What He Thought, and Why it Matters

Jesse Norman at Literary Review:

The received view of Smith is as the founding father of laissez-faire economics (the institute that bears his name certainly provided intellectual fuel to the laissez-faire policies of Margaret Thatcher). But as Norman – mostly correctly – argues, this is wrong, or at least an incomplete view. His goal is to round it out. He is not engaged, however, in just an intellectual exercise. He is battling for the soul of modern conservatism and he wants Smith on his side.

The received view of Smith is as the founding father of laissez-faire economics (the institute that bears his name certainly provided intellectual fuel to the laissez-faire policies of Margaret Thatcher). But as Norman – mostly correctly – argues, this is wrong, or at least an incomplete view. His goal is to round it out. He is not engaged, however, in just an intellectual exercise. He is battling for the soul of modern conservatism and he wants Smith on his side.

In July 2008, a ten-foot statue of Smith was unveiled in Edinburgh. Behind him is a beehive, a tribute to Smith’s views on the link between individual endeavour and social order. His hand rests on a globe, a reminder of his support for free trade. The timing was inauspicious.

more here.

Left Bank – existentialism, jazz and the miracle of Paris in the 1940s

Stuart Jeffries in The Guardian:

On August 1943, the sales team at Gallimard noticed something odd. The publisher’s new 700-page philosophical tome was selling unexpectedly well. Was it because Jean-Paul Sartre’s thoughts on freedom and responsibility in Being and Nothingness resonated with Parisians enduring Nazi occupation? Not quite. It was because the book weighed exactly one kilogram and so was a perfect substitute for copper weights, which had been sold on the black market or melted down for ammunition. Agnès Poirier’s engaging romp through the decade in which Paris rose from wartime shame to assert its claims to be world capital of art, philosophy and turtlenecks teems with such vignettes. When Ernest Hemingway arrived in Paris with fellow allied liberators in August 1944, for instance, he parked his Jeep outside 7 Rue des Grands Augustins – Picasso’s wartime studio. No one was in, so he left his impeccably butch calling card – a bucket of grenades, plus a note reading: “To Picasso from Hemingway”. Poirier never tells us what happened to those grenades.

On August 1943, the sales team at Gallimard noticed something odd. The publisher’s new 700-page philosophical tome was selling unexpectedly well. Was it because Jean-Paul Sartre’s thoughts on freedom and responsibility in Being and Nothingness resonated with Parisians enduring Nazi occupation? Not quite. It was because the book weighed exactly one kilogram and so was a perfect substitute for copper weights, which had been sold on the black market or melted down for ammunition. Agnès Poirier’s engaging romp through the decade in which Paris rose from wartime shame to assert its claims to be world capital of art, philosophy and turtlenecks teems with such vignettes. When Ernest Hemingway arrived in Paris with fellow allied liberators in August 1944, for instance, he parked his Jeep outside 7 Rue des Grands Augustins – Picasso’s wartime studio. No one was in, so he left his impeccably butch calling card – a bucket of grenades, plus a note reading: “To Picasso from Hemingway”. Poirier never tells us what happened to those grenades.

In one of my favourite moments Simone de Beauvoir pauses on the Pont Neuf after a nuit blanche of drinking with Sartre, Arthur Koestler and Albert Camus. Looking sadly into the Seine, she sobs over the tragedy of the human condition. “I do not understand why we do not throw ourselves into the water!” she wails to Sartre who, also crying, replies: “Well, let’s do it!” It would take a heart of stone not to laugh. But what is the human condition? Sartre defined it shortly after the liberation. “We were never freer,” he wrote, “than during the German occupation. Since the Nazi venom was poisoning our very own thinking, our every free thought was a victory. The circumstances, often atrocious, of our fight allowed us to live openly this torn and unbearable situation one calls the Human Condition.” But, Poirier points out, that freedom was dubiously won. De Beauvoir signed a form denying she was Jewish so she could continue teaching in occupied Paris. While she and Sartre were never freer, Parisian Jews were being rounded up by Parisian cops and murdered in Nazi death camps.

More here.

Saturday Poem

To S, After Years Apart

Dusk. The horse no one calls

begins to amble home from the fields.

I open the door of time

and breath the misty, incomparable autumn.

The I go again to find the old woman

who lives just beyond the turn

in the road. She has a potion

that cures the ailments of love.

Half our lives we’ve been sick

with a passion that bent our bones

the way a child bends a sapling in play

pulling the leaves to the ground.

By now, nothing can untangle

the branches.

But as I knew, the old woman is gone.

Her house long ago abandoned.

Night will come soon and dark solitude.

I’ll sit by the fire and watch

the wood of fate burn. It takes

many years to turn to ash.

Then our confused and inconsolable

passion will twist itself

around my heart like smoke

drifting from the chimney.

by Lou Lipsitz

from Seeking the Hook

Signal Books, 1997

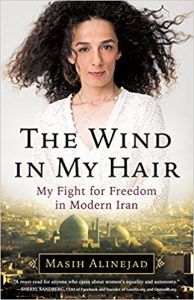

The Woman Whose Hair Frightens Iran

Rafia Zakaria in the New York Times:

When Masih Alinejad was a girl in the tiny Iranian village of Ghomikola, her father — who eked out a living selling chickens, ducks and eggs — once brought home a thick yellow stick. Her mother, the village tailor, cut it into six tiny pieces at her husband’s instruction. Each child got one, including the youngest, our author. The yellow stick was a banana, a fruit that the poor family had never seen or tasted. Alinejad, the rebel of the lot, didn’t listen when told to throw the skin away; she sneaked it to school the next day to show off to her friends.

When Masih Alinejad was a girl in the tiny Iranian village of Ghomikola, her father — who eked out a living selling chickens, ducks and eggs — once brought home a thick yellow stick. Her mother, the village tailor, cut it into six tiny pieces at her husband’s instruction. Each child got one, including the youngest, our author. The yellow stick was a banana, a fruit that the poor family had never seen or tasted. Alinejad, the rebel of the lot, didn’t listen when told to throw the skin away; she sneaked it to school the next day to show off to her friends.

She got away with it, but the episode was a precursor of what is to come; hers is a life of rebellions big and small followed by ignominious and sometimes draconian punishments. At 18, Alinejad, who would ultimately rise from her humble beginnings to become one of Iran’s top journalists, is carried off to prison. She has been stealing books and carrying on with a ragtag group of feverish ideologues whose crime is printing pamphlets calling for greater dissent in Iranian society. It is enough to get them all arrested.

She got away with it, but the episode was a precursor of what is to come; hers is a life of rebellions big and small followed by ignominious and sometimes draconian punishments. At 18, Alinejad, who would ultimately rise from her humble beginnings to become one of Iran’s top journalists, is carried off to prison. She has been stealing books and carrying on with a ragtag group of feverish ideologues whose crime is printing pamphlets calling for greater dissent in Iranian society. It is enough to get them all arrested.

When Alinejad is finally let out, she is a changed woman — and not only because of the imprisonment. She is also pregnant, a fact that she discovers during her internment.

More here.

Scientists trace high-energy cosmic neutrino to its birthplace

Kathryn Jepsen in Symmetry:

On September 22, 2017, a tiny but energetic particle pierced Earth’s atmosphere and smashed into the planet near the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station in Antarctica. The collision set loose a second particle, which lit a blue streak through the clear ice.

On September 22, 2017, a tiny but energetic particle pierced Earth’s atmosphere and smashed into the planet near the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station in Antarctica. The collision set loose a second particle, which lit a blue streak through the clear ice.

Luckily for science, the first particle was a neutrino, and the strike occurred within the cubic kilometer that makes up the IceCube neutrino experiment. Its detectors recorded the hit and sent out a public alert. The trail of light left behind by the second particle, a muon, pointed back to an intriguing object 4 billion light-years away: a violent, particle-flinging galaxy called a blazar, powered by a supermassive black hole.

This is the first time scientists have found evidence of the birthplace of an ultra-high-energy cosmic neutrino. And it is the second big result—after an August 2017 blockbuster from the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory and a band of additional experiments—in what scientists are calling a new era of multi-messenger astronomy.

In multi-messenger astronomy, experiments work together to study two or more different kinds of signals, such as gamma rays and neutrinos, from a single highly energetic event in a galaxy far away, says Regina Caputo, analysis coordinator for the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope’s Large Area Telescope instrument.

More here.

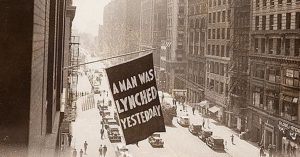

What Lynchings in 19th Century US Can Teach Us About ‘New India’

Asim Ali in The Wire:

The word ‘lynching’, which has recently flooded our newspapers, has an American origin. It entered into popular American usage in the second half of the 19th century. At least 3,500 lynchings occurred in America between 1865 and 1920, mostly in Southern America during the period of black disenfranchisement and the enactment of racist Jim Crow laws. These were not random and relatively spontaneous acts of violence, but purposeful and deeply political acts. The overarching context was the end of civil war and the need to enforce white supremacy and control AfricanAmericans in the absence of slavery.

The word ‘lynching’, which has recently flooded our newspapers, has an American origin. It entered into popular American usage in the second half of the 19th century. At least 3,500 lynchings occurred in America between 1865 and 1920, mostly in Southern America during the period of black disenfranchisement and the enactment of racist Jim Crow laws. These were not random and relatively spontaneous acts of violence, but purposeful and deeply political acts. The overarching context was the end of civil war and the need to enforce white supremacy and control AfricanAmericans in the absence of slavery.

While the justification given for these ritualised, public acts of violence was retribution for crimes committed by African Americans – usually involving (generally fabricated) accusations of sexual offences against white women – the deeper context was always the desire to deny political and social equality to the newly emancipated black population. As the then South Carolina Governor, Benjamin Tillman bluntly put it: “We of the South have never recognised the right of the negro to govern white men, and we never will. We have never believed him to be the equal of the white man, and we will not submit to his gratifying his lust on our wives and daughters without lynching him.”

There is a vast literature explaining and analysing lynchings in America, and it might be instructive to study it to better understand our current moment. Specifically, there are three broad lessons to be gained by turning to this horrific episode of American history.

More here.

The Maps of Israeli Settlements That Shocked Barack Obama

Adam Entous in The New Yorker:

One afternoon in the spring of 2015, a senior State Department official named Frank Lowenstein paged through a government briefing book and noticed a map that he had never seen before. Lowenstein was the Obama Administration’s special envoy on Israeli-Palestinian negotiations, a position that exposed him to hundreds of maps of the West Bank. (One adorned his State Department office.)

One afternoon in the spring of 2015, a senior State Department official named Frank Lowenstein paged through a government briefing book and noticed a map that he had never seen before. Lowenstein was the Obama Administration’s special envoy on Israeli-Palestinian negotiations, a position that exposed him to hundreds of maps of the West Bank. (One adorned his State Department office.)

Typically, those maps made Jewish settlements and outposts look tiny compared to the areas where the Palestinians lived. The new map in the briefing book was different. It showed large swaths of territory that were off limits to Palestinian development and filled in space between the settlements and the outposts. At that moment, Lowenstein told me, he saw “the forest for the trees”—not only were Palestinian population centers cut off from one another but there was virtually no way to squeeze a viable Palestinian state into the areas that remained. Lowenstein’s team did the math. When the settlement zones, the illegal outposts, and the other areas off limits to Palestinian development were consolidated, they covered almost sixty per cent of the West Bank.

More here.

Brave And Tragic: A Story Of Being One Of The Mengele Twins In The Holocaust

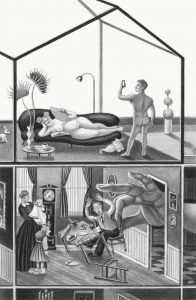

Self-Invasions and the Invaded Self

Rochelle Gurstein at The Baffler:

WHAT DO WE LOSE WHEN WE LOSE OUR PRIVACY? This question has become increasingly difficult to answer, living as we do in a society that offers boundless opportunities for men and women to expose themselves (in all dimensions of that word) as never before, to commit what are essentially self-invasions of privacy. Although this is a new phenomenon, it has become as ubiquitous as it is quotidian, and for that reason, it is perhaps one of the most telling signs of our time. To get a sense of the sheer range of unconscious exhibitionism, we need only think of the popularity of reality TV shows, addiction-recovery memoirs, and cancer diaries. Then there are the banal but even more conspicuous varieties, like soaring, all-glass luxury apartment buildings and hotels in which inhabitants display themselves in all phases of their private lives to the casual glance of thousands of city walkers below. Or the incessant sound of people talking loudly—sometimes gossiping, sometimes crying—on their cell phones, broadcasting to total strangers the intimate details of their lives.

WHAT DO WE LOSE WHEN WE LOSE OUR PRIVACY? This question has become increasingly difficult to answer, living as we do in a society that offers boundless opportunities for men and women to expose themselves (in all dimensions of that word) as never before, to commit what are essentially self-invasions of privacy. Although this is a new phenomenon, it has become as ubiquitous as it is quotidian, and for that reason, it is perhaps one of the most telling signs of our time. To get a sense of the sheer range of unconscious exhibitionism, we need only think of the popularity of reality TV shows, addiction-recovery memoirs, and cancer diaries. Then there are the banal but even more conspicuous varieties, like soaring, all-glass luxury apartment buildings and hotels in which inhabitants display themselves in all phases of their private lives to the casual glance of thousands of city walkers below. Or the incessant sound of people talking loudly—sometimes gossiping, sometimes crying—on their cell phones, broadcasting to total strangers the intimate details of their lives.

more here.

‘The House of Islam’ by Ed Husain

Christopher de Bellaigue at The Guardian:

Of the world’s 1.6 billion Muslims a very large number – perhaps a majority – observed the Ramadan fast last month. This doesn’t simply mean abstaining from food and water during the hours of daylight (as well as sex and cigarettes), but in many cases involves a deliberate reappraisal of one’s relation to God and the world, with more prayers and philanthropy and less shopping.

Of the world’s 1.6 billion Muslims a very large number – perhaps a majority – observed the Ramadan fast last month. This doesn’t simply mean abstaining from food and water during the hours of daylight (as well as sex and cigarettes), but in many cases involves a deliberate reappraisal of one’s relation to God and the world, with more prayers and philanthropy and less shopping.

Of all the obligations that define Islam, Ramadan arouses perhaps the most irritation among some outsiders. A practice that places such a strain on the body is surely an affront to reason. Nor does it seem to make economic sense for workers to be tired and unproductive while declining to perform their allotted roles as consumers with credit ratings. And yet the west has absorbed Ramadan, if uneasily, with supermarket promotions for dates (the Prophet’s favoured breakfast), school assemblies on the subject and “What is Ramadan?” features even in the Sun.

more here.