Scott Samuelson in Aeon:

In 1826, at the age of 20, John Stuart Mill sank into a suicidal depression, which was bitterly ironic, because his entire upbringing was governed by the maximisation of happiness. How this philosopher clambered out of the despair generated by an arch-rational philosophy can teach us an important lesson about suffering. Inspired by Jeremy Bentham’s ideals, James Mill’s rigorous tutelage of his son involved useful subjects subordinated to the utilitarian goal of bringing about the greatest good for the greatest number. Music played a small part in the curriculum, as it was sufficiently mathematical – an early ‘Mozart for brain development’. Otherwise, subjects useless to material improvement were excluded. When J S Mill applied to Cambridge at the age of 15, he’d so mastered law, history, philosophy, economics, science and mathematics that they turned him away because their professors didn’t have anything more to teach him.

In 1826, at the age of 20, John Stuart Mill sank into a suicidal depression, which was bitterly ironic, because his entire upbringing was governed by the maximisation of happiness. How this philosopher clambered out of the despair generated by an arch-rational philosophy can teach us an important lesson about suffering. Inspired by Jeremy Bentham’s ideals, James Mill’s rigorous tutelage of his son involved useful subjects subordinated to the utilitarian goal of bringing about the greatest good for the greatest number. Music played a small part in the curriculum, as it was sufficiently mathematical – an early ‘Mozart for brain development’. Otherwise, subjects useless to material improvement were excluded. When J S Mill applied to Cambridge at the age of 15, he’d so mastered law, history, philosophy, economics, science and mathematics that they turned him away because their professors didn’t have anything more to teach him.

The young Mill soldiered on with efforts for social reform, but his heart wasn’t in it. He’d become a utilitarian machine with a suicidal ghost inside. With his well-tuned calculative abilities, the despairing philosopher put his finger right on the problem:

[I]t occurred to me to put the question directly to myself: ‘Suppose that all your objects in life were realised; that all the changes in institutions and opinions which you are looking forward to could be completely effected at this very instant: would this be a great joy and happiness to you?’ And an irrepressible self-consciousness distinctly answered: ‘No!’ At this my heart sank within me: the whole foundation on which my life was constructed fell down.

For most of our history, we’ve seen suffering as a mystery, and dealt with it by placing it in a complex symbolic framework, often where this life is conceived as a testing ground. In the 18th century, the mystery of suffering becomes the ‘problem of evil’, in which pain and misery turn into clear-cut refutations of God’s goodness to utilitarian reformers. As Mill says of his father: ‘He found it impossible to believe that a world so full of evil was the work of an Author combining infinite power with perfect goodness and righteousness.’

For a utilitarian, the idea of worshipping the creator of suffering is not only absurd, it undercuts the purpose of morality. It channels our energies toward the acceptance of what we should remedy. To revere the natural order could even turn us into moral monsters. Mill says: ‘In sober truth, nearly all the things which men are hanged or imprisoned for doing to one another, are nature’s every day performances.’ What Mill calls the ‘Religion of Humanity’ involves pushing aside the old conception of God, and taking over responsibility for what happens in the world. We’re to become the good architect that God never was.

More here.

Like most other neurological disorders, Huntington’s disease has proved to be a costly and frustrating target for drug developers. But it also has distinctive features that make it a good match for treatments that target genes. It arises from a mutation in a single gene that encodes the protein huntingtin, and a disease-causing copy of the gene can be readily distinguished from a normal copy by the presence of an

Like most other neurological disorders, Huntington’s disease has proved to be a costly and frustrating target for drug developers. But it also has distinctive features that make it a good match for treatments that target genes. It arises from a mutation in a single gene that encodes the protein huntingtin, and a disease-causing copy of the gene can be readily distinguished from a normal copy by the presence of an  People are gullible. Humans can be duped by liars and conned by frauds; manipulated by rhetoric and beguiled by self-regard; browbeaten, cajoled, seduced, intimidated, flattered, wheedled, inveigled, and ensnared. In this respect, humans are unique in the animal kingdom.

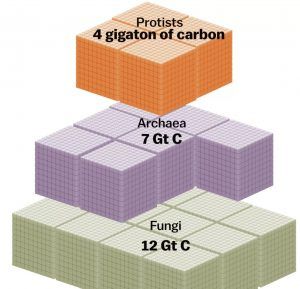

People are gullible. Humans can be duped by liars and conned by frauds; manipulated by rhetoric and beguiled by self-regard; browbeaten, cajoled, seduced, intimidated, flattered, wheedled, inveigled, and ensnared. In this respect, humans are unique in the animal kingdom. By weight, human beings are insignificant.

By weight, human beings are insignificant. Two reports last week exposed both the changing character of the labour market and the degree to which the power of the organised working class has eroded.

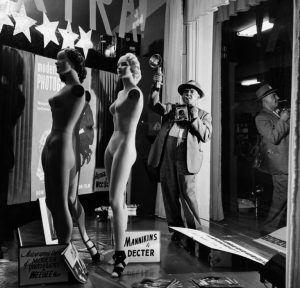

Two reports last week exposed both the changing character of the labour market and the degree to which the power of the organised working class has eroded. Usher Fellig was a greenhorn, a hungry shtetl child from eastern Europe who spoke no English. When he came through Ellis Island in 1909, at ten years old, he reinvented himself, as so many immigrants do. In his first years in New York, Usher became Arthur, a Lower East Side street kid who was eager to get out of what he called “the lousy tenements,” earn a living, impress girls, make a splash. He had turned his name (slightly) less Jewish and his identity (somewhat) more American, as much as he could make it. As a young man, he was shy, awkward, broke, and unpolished, and at fourteen, he became a seventh-grade dropout. He was also smart, ambitious, funny, and (as he and then his fellow New Yorkers and eventually the world discovered) enormously expressive when you put a camera in his hands.

Usher Fellig was a greenhorn, a hungry shtetl child from eastern Europe who spoke no English. When he came through Ellis Island in 1909, at ten years old, he reinvented himself, as so many immigrants do. In his first years in New York, Usher became Arthur, a Lower East Side street kid who was eager to get out of what he called “the lousy tenements,” earn a living, impress girls, make a splash. He had turned his name (slightly) less Jewish and his identity (somewhat) more American, as much as he could make it. As a young man, he was shy, awkward, broke, and unpolished, and at fourteen, he became a seventh-grade dropout. He was also smart, ambitious, funny, and (as he and then his fellow New Yorkers and eventually the world discovered) enormously expressive when you put a camera in his hands. The show’s visual grammar reflects this anxiety and paranoia. Murai’s choice to use film is a potent reminder that this is still fiction, but the choice makes it all the more real—not only because film adds texture, but also because when the celluloid occasionally pops, that jumpiness contributes to the show’s overall tone. Late night, after the strip club gets out, there’s an Edward Hopper tableau of small, illuminated spaces engulfed in darkness. The introduction of magical realism is straight out of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, only Atlanta is a black Macondo made famous by Magic City, and instead of a woman floating up into the sky, there’s a disappearing club promoter and an invisible sports car.

The show’s visual grammar reflects this anxiety and paranoia. Murai’s choice to use film is a potent reminder that this is still fiction, but the choice makes it all the more real—not only because film adds texture, but also because when the celluloid occasionally pops, that jumpiness contributes to the show’s overall tone. Late night, after the strip club gets out, there’s an Edward Hopper tableau of small, illuminated spaces engulfed in darkness. The introduction of magical realism is straight out of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, only Atlanta is a black Macondo made famous by Magic City, and instead of a woman floating up into the sky, there’s a disappearing club promoter and an invisible sports car. The credit for arguably the best idea ever for a White House event goes to the fertile brain of Richard Goodwin. In a note to Jacqueline Kennedy in November 1961, the president’s aide was to the point: “How about a dinner for the American winners of the Nobel Prize?” Within six months, the largest social event of the New Frontier had occurred. By contemporary accounts, it was a smash. And it has resonated through the decades as a symbol of what that “one brief, shining moment” was capable of on its best days, and of the impact a White House can have on American culture and the creative minds who inhabit it. Comparisons to the disgusting atmosphere of the present are obvious. John Kennedy was pleased, but not entirely. According to his and his wife’s friend, the artist William Walton, the president called him later to complain about the woman who had been seated on his right, Ernest Hemingway’s fourth wife and widow of a year, Mary, who gave him repeated guff for his Cuba policy; Kennedy was more impressed by the dignified woman on his left, Katherine Marshall, the widow of George C. Marshall, the World War II commander and architect of the postwar reconstruction plan that bore his name. “Well, your friend Mary Hemingway is the biggest bore I’d had for a long time,” Walton quoted JFK as saying. “If I hadn’t had Mrs. Marshall I would have had a terrible night.” Walton couldn’t say much in reply: Mary Hemingway was right next to him in his Georgetown home when the call came.

The credit for arguably the best idea ever for a White House event goes to the fertile brain of Richard Goodwin. In a note to Jacqueline Kennedy in November 1961, the president’s aide was to the point: “How about a dinner for the American winners of the Nobel Prize?” Within six months, the largest social event of the New Frontier had occurred. By contemporary accounts, it was a smash. And it has resonated through the decades as a symbol of what that “one brief, shining moment” was capable of on its best days, and of the impact a White House can have on American culture and the creative minds who inhabit it. Comparisons to the disgusting atmosphere of the present are obvious. John Kennedy was pleased, but not entirely. According to his and his wife’s friend, the artist William Walton, the president called him later to complain about the woman who had been seated on his right, Ernest Hemingway’s fourth wife and widow of a year, Mary, who gave him repeated guff for his Cuba policy; Kennedy was more impressed by the dignified woman on his left, Katherine Marshall, the widow of George C. Marshall, the World War II commander and architect of the postwar reconstruction plan that bore his name. “Well, your friend Mary Hemingway is the biggest bore I’d had for a long time,” Walton quoted JFK as saying. “If I hadn’t had Mrs. Marshall I would have had a terrible night.” Walton couldn’t say much in reply: Mary Hemingway was right next to him in his Georgetown home when the call came. How easy it would be,

How easy it would be,  The 20th century was a remarkably productive one for physics. First, Albert Einstein’s

The 20th century was a remarkably productive one for physics. First, Albert Einstein’s  Ask people to name the key minds that have shaped America’s burst of radical right-wing attacks on working conditions, consumer rights and public services, and they will typically mention figures like free market-champion Milton Friedman, libertarian guru Ayn Rand, and laissez-faire economists Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises.

Ask people to name the key minds that have shaped America’s burst of radical right-wing attacks on working conditions, consumer rights and public services, and they will typically mention figures like free market-champion Milton Friedman, libertarian guru Ayn Rand, and laissez-faire economists Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises. It is election season in

It is election season in  What’s especially impressive about this adaptation is not only that it is enjoyable, but that it directly confronts the problem of addiction without glamorising it. Other dramas about womanising addicts—for example Mad Men or Californication—tend to focus on the debauchery as much as the interior consequences; this makes it easy for the viewer to avoid processing the trauma. Watching Mad Men’s Don Draper pour himself yet another glass of whiskey, having hit yet another rock bottom, doesn’t quell the desire (provoked by the sexy depiction of the world of the programme) to reach for a cigarette and a whiskey yourself. Even in Channel 4’s Sherlock, the detective’s opium habit is seen as a facet of his genius: a necessary method for him to open the doors of perception. There is something beguiling and (literally) intoxicating about watching someone dance so close to the cliff edge. Indulging this behaviour onscreen can make it seem attractive rather than repellent.

What’s especially impressive about this adaptation is not only that it is enjoyable, but that it directly confronts the problem of addiction without glamorising it. Other dramas about womanising addicts—for example Mad Men or Californication—tend to focus on the debauchery as much as the interior consequences; this makes it easy for the viewer to avoid processing the trauma. Watching Mad Men’s Don Draper pour himself yet another glass of whiskey, having hit yet another rock bottom, doesn’t quell the desire (provoked by the sexy depiction of the world of the programme) to reach for a cigarette and a whiskey yourself. Even in Channel 4’s Sherlock, the detective’s opium habit is seen as a facet of his genius: a necessary method for him to open the doors of perception. There is something beguiling and (literally) intoxicating about watching someone dance so close to the cliff edge. Indulging this behaviour onscreen can make it seem attractive rather than repellent. Around the time that Imasuen was getting yelled at by his mother, the author of “Purple Hibiscus,” Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, who is now regarded as one of the most vital and original novelists of her generation, was living in a poky apartment in Baltimore, writing the last sections of her second book. She was twenty-six. “Purple Hibiscus,” published the previous fall, had established her reputation as an up-and-coming writer, but she was not yet well known.

Around the time that Imasuen was getting yelled at by his mother, the author of “Purple Hibiscus,” Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, who is now regarded as one of the most vital and original novelists of her generation, was living in a poky apartment in Baltimore, writing the last sections of her second book. She was twenty-six. “Purple Hibiscus,” published the previous fall, had established her reputation as an up-and-coming writer, but she was not yet well known. Heron the critic was also one of the figures responsible for introducing the American abstract expressionists to a British audience. Although he was later to accuse Pollock, De Kooning et al (but not Rothko) of cultural imperialism and not being painterly enough, the scale of their pictures, their rhythm, saturated palette and insistence that each part of the canvas was as important as every other, had a profound effect on him. Heron believed that, “Painting is thinking with one’s hand; or with one’s arm; in fact with one’s whole body,” and the epic AbEx works represented his aphorism in action.

Heron the critic was also one of the figures responsible for introducing the American abstract expressionists to a British audience. Although he was later to accuse Pollock, De Kooning et al (but not Rothko) of cultural imperialism and not being painterly enough, the scale of their pictures, their rhythm, saturated palette and insistence that each part of the canvas was as important as every other, had a profound effect on him. Heron believed that, “Painting is thinking with one’s hand; or with one’s arm; in fact with one’s whole body,” and the epic AbEx works represented his aphorism in action.