Freddy Gray in The Spectator:

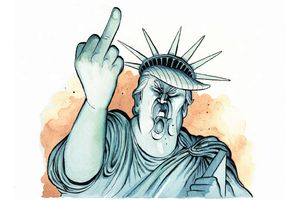

It’s time to face reality. Barring a dramatic and unprecedented reversal of fortune, Donald Trump is going to be the Republican candidate for the presidential election on 8 November. Which means that, by January, a fulminating demagogue with more than a whiff of the mad dictator about him could be in charge of the most powerful nation on earth. This says something disturbing about the state of America. The most benevolent superpower in history is turning nasty. In Donald Trump’s America, greed isn’t just good — it is great. As he put it in his victory speech in Las Vegas last week, ‘We’re going to get greedy for the United States. We’re gonna grab and grab and grab. We’re gonna bring in so much money and so much everything. We’re going to Make America Great Again, I’m telling you folks.’ The crowd screamed. In Donald Trump’s America, viciousness is beautiful. As he put it in another victory speech in South Carolina, ‘There’s nothing easy about running for president. It’s tough, it’s nasty, it’s mean, it’s vicious, it’s… beautiful.’

It’s time to face reality. Barring a dramatic and unprecedented reversal of fortune, Donald Trump is going to be the Republican candidate for the presidential election on 8 November. Which means that, by January, a fulminating demagogue with more than a whiff of the mad dictator about him could be in charge of the most powerful nation on earth. This says something disturbing about the state of America. The most benevolent superpower in history is turning nasty. In Donald Trump’s America, greed isn’t just good — it is great. As he put it in his victory speech in Las Vegas last week, ‘We’re going to get greedy for the United States. We’re gonna grab and grab and grab. We’re gonna bring in so much money and so much everything. We’re going to Make America Great Again, I’m telling you folks.’ The crowd screamed. In Donald Trump’s America, viciousness is beautiful. As he put it in another victory speech in South Carolina, ‘There’s nothing easy about running for president. It’s tough, it’s nasty, it’s mean, it’s vicious, it’s… beautiful.’

The Trump phenomenon seems too mad to be real. But it’s happening, folks, and it’s yuge. Pundits who dismiss Trump’s chances do so at their peril. In November, Donald Trump will almost certainly face Hillary Clinton, a woman who has not yet won a competitive major election and who is a perfect example of the fetid elite that American voters so detest. The odds are still against Trump. But then, a few months ago, he was a 50-1 shot to be the Republican nominee. Look at him now. Trump’s critics compare his candidacy to that of Barry Goldwater in 1964, an insurgent campaign that wooed the radical right only then to be slaughtered by Lyndon B. Johnson, a machine Democrat. But the comparison misunderstands and undervalues Trump’s strengths. In his celebrity and ability to appeal to very different voters, Trump more resembles Ronald Reagan, a man who can remodel politics in his own image. The depth and breadth of Trump’s appeal is endlessly surprising. He is more popular than other Republican candidates among men, women, whites, blacks, Hispanics, old, young, married and unmarried, evangelicals and non-evangelicals, those with college degrees and those without (‘I love the poorly educated,’ he said last week, a comment which prompted much chortling from the better educated). Trump has majority support among Republican voters who earn a lot of money and those who earn little, from self-described conservatives and moderates. As you might expect from someone who promises to build a wall to keep out Mexicans, he wins with people who worry most about immigration. But he also wins with those who cite the economy and terrorism as their chief concerns. In short, he wins a lot. Since the financial crash, and despite the so-called recovery, an ever larger number of Americans feel angry at the system. The Donald embodies their rage and multiplies it as in a hall of mirrors.

The consolation — and how people will cling to it in the coming weeks! — is that Trump probably won’t be president. According to the polls, a large majority of Americans hold an ‘unfavourable’ opinion of him. He may reflect the rage of Republican voters but no one in the history of the republic has been as reviled as Trump and reached the White House.

More here.

Tom Burgis at The Financial Times: