by Bill Benzon

No, I don’t think it is, morally repugnant; quite the contrary. But it IS controversial and problematic, and that’s what I want to deal with in this post. But I don’t want to come at it directly. I want to ease into it.

As some of you may have gathered, I have been trained as an academic literary critic, and academic literary criticism forswore value judgments in the mid-1950s, though surreptitious reneged on the deal in the 1980s. In consequence, overt ethical criticism is a bit strange to me. I’m not sure how to do it. This post is thus something of a trial run.

I take my remit as an ethical critic from “Literature as Equipment for Living” by the literary critic, Kenneth Burke [1]. Using words and phrases from several definitions of the term “strategy” (in quotes in the following passage), he asserts that (p. 298):

… surely, the most highly alembicated and sophisticated work of art, arising in complex civilizations, could be considered as designed to organize and command the army of one’s thoughts and images, and to so organize them that one “imposes upon the enemy the time and place and conditions for fighting preferred by oneself.” One seeks to “direct the larger movements and operations” in one’s campaign of living. One “maneuvers,” and the maneuvering is an “art.”

Given the subject matter of The Wind Rises, Burke’s military metaphors are oddly apt, but also incidental. The question he would have us put to Mizayaki’s film, then, might go something like this: For someone who is trying to make sense of the world, not as a mere object of thought, but as an arena in which they must act, what “equipment” does The Wind Rises afford them?

I note that it is one thing for the critic to answer the question for his or herself. The more important question, however, is the equipment the film affords to others. But how can any one critic answer that? I take it then that ethical criticism must necessarily be an open-ended conversation with others. In this case, I will be “conversing” with Miyazaki himself and with Inkoo Kang, a widely published film critic.

What About the Pyramids?

The Wind Rises, as you may know, is a highly fictionalized account of the early life of Jiro Horikoshi, an aeronautical engineer best known for designing the Mitsubishi A6M Zero. At the beginning of World War II the Zero was one of the finest military aircraft in the world. The film is episodic, presenting disconnected incidents in Horikisohi’s life from his childhood up through the end of World War II.

About halfway through the film, when Horikoshi is a young man employed by Mitsubishi, he and several other engineers are sent to Germany to learn about their aviation technology. While some are summoned back to Japan, and Horikoshi’s friend, Honjo, is to remain in Germany, Horikoshi is sent west, “to see the world”. If I knew something about the history of steam locomotives I might be able to identify the engine in this frame grab and thereby know where Horikoshi was in the following scene:

Regardless of his geographical locale, Miyazaki places us inside the train and Horikoshi is sitting in a compartment when he is joined by Gianni Caproni:

But Caproni isn’t really there. Just where and how he is, that’s not clear – this is an aspect of Miyazaki’s metaphysical legerdemain, which we’ll have to leave unexamined.

Caproni is an Italian aeronautical engineer who is something of a dreamtime mentor to Horikoshi. He has appeared twice before in the film, once when Horikoshi was a boy trying to figure out what he wanted to do when he grew up, and then later when, as college student, Horikoshi was helping to put out fires caused by the 1923 Kanto Earthquake. This third time Caproni takes Horikoshi into the air, as he’d done in that first dream, and tours him around a bomber he is about deliver to the government.

Horikoshi is amazed at the plane and remarks: “Japan could never build anything as grand and as beautiful at this. The country is too poor and backward.” This sentiment is something of a motif in the film; we’ve heard it before and it and recurs again. Given the devastation that Japan managed to wreak throughout the first half of the 20th century, not just in the mid-century war in the Pacific with America, this sentiment might seem self-indulgent. And it’s certainly not true of 21st century Japan.

But the film is not about 21st century Japan. It’s about Japan in the first half of the 20th century. In an interview with the Asahi Shimbun [2] Miyazaki remarks:

Including myself, a generation of Japanese men who grew up during a certain period have very complex feelings about World War II, and the Zero symbolizes our collective psyche. Japan went to war out of foolish arrogance, caused trouble throughout the entire East Asia, and ultimately brought destruction upon itself. […] But for all this humiliating history, the Zero represented one of the few things that we Japanese could be proud of. There were 322 Zero fighters at the start of the war. They were a truly formidable presence, and so were the pilots who flew them. […]

The majority of fanatical Zero fans in Japan today have a serious inferiority complex, which drives them to overcompensate for their lack of self-esteem by latching on to something they can be proud of. The last thing I want is for such people to zero in on Horikoshi’s extraordinary genius and achievement as an outlet for their patriotism and inferiority complex. In making this film, I hope to have snatched Horikoshi back from those people. It’s not entirely clear to me just how Miyazaki thinks this film would “snatch” Horikoshi from the patriots, but let’s bracket that question; we’ve got enough to do. I simply want to register his pride in the plane itself, the pilots, and what that represented.

Moreover, we must note that Miyazaki is living in a world in which a person’s identity is bound-up with the nation-state in which one lives. The world in which we, the readers of 3 Quarks Daily, live is like that as well. What does it mean to live in a poor and backward nation, one trying desperately to play technological catch-up, as Japan was in the late 19th century and during much of the 20th century? How does it feel to be a citizen of a 2nd or 3rd rate nation? What does it do to your sense of importance?

Correlatively, what does it mean to live in a wealthy and technologically sophisticated world hegemon? Yes, I know, The Wind Rises isn’t about the United States, but that’s where I’m from. If I’m going to use this film in making sense of my world, then that’s a question the film puts to me. And it’s not the only such question, not by a long shot.

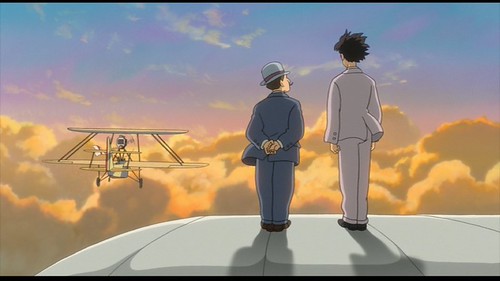

Let’s return to the film itself. Caproni is touring Horikoshi around his plane and takes him outside where they walk along the top wing. Miyazaki poses them against a glorious sky:

Caproni: “Which would you choose, a world with pyramids or a world without?”

Horikoshi: “What do you mean?”

Caproni: “Humanity has always dreamt of flying, but the dream is cursed. My aircraft are destined to become tools for slaughter and destruction.”

Horikoshi: “I know.”

Caproni: “But still, I choose a world with pyramids in it. Which world will you choose?”

Horikoshi: “I just want to create beautiful airplanes.”

At this point two things were on my mind the first time I watched the film. In the first place, Horikoshi seems to be evading the question. Yes, he wants to make airplanes, but he doesn’t quite respond to Caproni’s question about a world with pyramids.

The second thing on my mind: What’s with the pyramids? Yes, a great accomplishment, a wonder of the ancient world. So?

But in subsequent reading about the film, I found this remark in an article by Inkoo Kang [3]:

Jiro, as he’s referred to in the film, finds such beauty in airplanes and flight that he feverishly pursues the next level of killing machines for Mitsubishi, justifying his work by comparing his planes to the pyramids. The reference to the pharaohs might allude to the fact that Mitsubishi used Chinese and Korean slave labor to build Jiro’s Zero planes. But the character never considers whether the slaves who died making those pyramids might not believe the results were worth their lives.

At this point my thoughts run in three directions: 1) It’s not Horikoshi who brings up the pyramids, as Kang says, but Caproni. 2) Nonetheless, she’s right in associating the pyramids with slave labor, even if there is recent scholarly opinion to the contrary [4], and through that making the connection with slave labor in building the Zeros. 3) Nonetheless, the pyramids ARE generally regarded as a remarkable human achievement.

Are we mistaken to believe that? I think not. But what are we to make of the human cost of their construction? How do we weigh that cost against the accomplishment? I’m not sure that we can. What we’ve got in the pyramids is an aweful conjunction, where I mean “awe” in the fullest sense of the word – and even if the pyramids weren’t built by slave labor, well, what about those who died constructing the Great Wall of China?

THAT’s the kind of world we live in. How is it possible to live in such a world?

Who Are They Going to Bomb?

Let’s consider another scene. It’s late in the film, near the end. Horikoshi and Honjo, his friend and colleague, are walking from the assembly building back to the office:

They’re talking about the bomber Honjo is in charge of. It needs a redesign so that it can be made lighter and the fuel tanks can be shielded from gunfire. But Honjo wasn’t allowed to undertake the redesign.

Honjo: “So without a redesign, Japan’s first advanced bomber only needs two or three hits and she’ll burn like a torch.”

Horikoshi: “And who are they going to bomb with it?”

Honjo: “China, Russia, Britain, the Netherlands, America.”

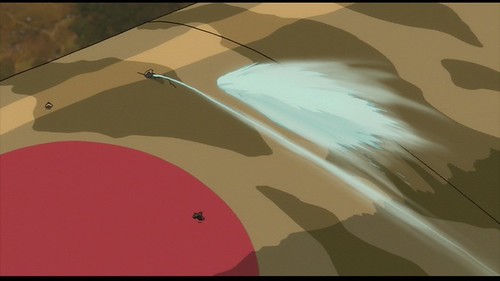

As they’re conversing we see those bombers in the air over a land that is bleeding smoke from the bombs that have landed:

Presumably they’ve been bombing China, otherwise, why would they be attacked by Chinese fighters (notice the wing markings below). And yes, these bombers do burn quickly.

Horikoshi: “Japan’ll blow up.”

Honjo: “We’re not arms merchants, we just wanna build good aircraft.”

Horikoshi” “That’s right.”

They acknowledge that their country is an aggressor nation and they fear that, in the end, Japan will collapse. But they just want to build good aircraft.

They’re compartmentalizing. They’re in denial. What choices did they have? I don’t know. I wasn’t there.

Now, at this point in the story Horikoshi has been in hiding from the secret police. Earlier he had been at a resort where he’d been friendly with an anti-Nazi German. Shortly after he returned to work the secret police showed up at the plant looking for him. Horikoshi’s bosses lied and made arrangements to protect him until things blew over. One of them mentioned that several of his friends had been taken without any reasons being given.

If Horikoshi had refused to work on warplanes, what would have happened to him? There is an abstract moral sense in which he was a free agent and could have refused. Practically, though, he was living in a militaristic authoritarian state that was quite willing to coerce people to the national will, or to murder them. Some people have refused the state in such circumstances. And some haven’t.

I don’t believe that anyone who hasn’t lived that situation can really know what they would do in those circumstances. Miyazaki understands that [5]:

“I think that both Jiro and Tatsuo Hori are greater men than I, so I can’t put myself beside them,” he says. “I’ve been very blessed to make animation for 50 years in peaceful times, while they lived in very volatile, violent times. But I think the peaceful time that we are living in is coming to an end.”

Miyazaki hasn’t had to make the kinds of decisions those men had to make. But, alas, we’re moving into a world where others have to make those kinds of decisions. In another interview Miyazaki remarks [6]:

I am against the use of nuclear power. But when I saw the press conference with the engineers working on the [Fukushima] power plants, answering questions, I saw the same type of purity of their soul that I portrayed in Jiro Horikoshi in the film. The problems of our civilization are so difficult that we can’t only put an “X” in a circle and say “Yes” or “No.”

And those nuclear engineers are hardly the only technologists facing the kind of decision that Horikoshi faced. Such decisions are legion in the world, and engineers aren’t the only ones who have to make them.

Miyazaki’s last assertion should be familiar enough to post-structuralists: no (false) binaries. This is not a world for purists. No matter what you do, you’re going to get dirty. How then, do you live the world?

Horikoshi’s World in Mine

Back in the 1960s I faced the military draft. I was opposed to the war in Vietnam, but when the lottery was introduced in 1969, I drew number 12. I was certain to be drafted if I didn’t volunteer first. At the time I was a senior at The Johns Hopkins University and that made me very desirable to the military. I was solicited by the Marines and, I’m sure, by at least one other branch of the military. By volunteering I would have some choice in my duty assignment. But if I were drafted, I’d lose all choice.

As a practical matter, it was unlikely that the Army would assign me to combat duty, not with those four years of elite education. I might not even have gone to Vietnam. But I would have been serving in the military at a time it was fighting a war I believed to be immoral.

What was I to do? I’ve heard stories of guys who did drugs the day before their physical in hopes that they’d fail the physical without being found out. I don’t know whether that actually worked for anyone, though it might have. I knew of psychiatrists who would write a letter, for a fee, that had a good chance of failing me out. Neither of those alternatives appealed to me. I could flee to Canada; I knew a graduate student who did that. But I wasn’t going to.

I declared myself to be a conscientious objector. That meant I was a pacifist with a religious objection to killing anyone for any reason. I thought long and hard about that, but my parents supported me, and I had the backing of the Chaplain at Johns Hopkins. So I filled out the forms and sent them in to my draft board. If they turned me down, well then I’d have to decide whether to enter the service or to begin a legal process that I might not win.

Fortunately my draft board granted me C.O. status. I didn’t have to enter the military. But I did have to serve two years of civilian service of a kind that was in some way comparable to non-combatant military duty (such as medical corps). My draft board gave me a bit of trouble over that, but the Chaplain was able to get some Congressmen to write on my behalf and I ended up serving two years as an assistant to the Chaplain of Johns Hopkins University.

I had to put my life on hold for two years. I regard that as a relatively low cost I had to pay in order to honor my conscience. Back in World War II conscientious objectors, mostly from conservative Christian denominations such as the Mennonites, were more in risk of prison than I was. Would I have gone to prison as the cost of serving my conscience? I don’t know. I didn’t have to face that choice.

Had I been in Horikoshi’s situation – and, though I’m not an engineer, I do understand his dedication to engineering – what would I have done? I don’t know.

Beyond Inkoo Kang’s Objection

Here’s Inkoo Kang’s basic objection to The Wind Rises [3]:

The Wind Rises is custom-made for postwar Japan, a nation that has yet to acknowledge, let alone apologize for, the brutality of its imperial past. Nearly 70 years after Emperor Hirohito’s surrender, the Japanese military and medical institutions’ greatest evils, like the orchestration of mass rape, the use of slave labor, and experimentation on live and conscious human beings, remain absent from school textbooks.

I think she overplays her hand (e.g. “custom-made”), but sure, if someone wants to read the film as ignoring Japan’s imperial past, they can do so.

Films are complex objects and it is easy to pick and choose incidents that are convenient for whatever case you want to make. But the right-wing nationalists Kang worries about have to ignore some things that are in the film in order to read it they way she claims the film can too easily be read. They have to ignore or misread the scene I discussed immediately above, and they have to ignore the fact that Horikoshi – in the film, I don’t know about real life – was under suspicion by the secret police. They have to ignore the fact that the film clearly shows Horikoshi, Honjo, and others going to Germany to acquire German technology.

Kang admits that some of these nationalists seem to have been unable to cut the film to their needs: “Indeed, some of his fellow citizens have already accused Miyazaki of being a ‘traitor’ and ‘anti-Japanese.’” That is, despite the fact that The Wind Rises is “custom-made” to facilitate their denial, it seems to have failed in that purpose. And it has failed despite the fact that it doesn’t come anywhere near to a full catalogue of Japanese atrocities during the war with America or in its broader imperial wars throughout the first half of the 20th century.

It seems to me that Kang is, in effect, reading the film from a transcendental point of view in which she has perfect knowledge of the world Miyazaki depicts but is also isolated from the decisions she is implicitly making about how those people should have lived their lives. Moreover she ignores much that is in the film, including Horikoshi’s marriage. To be sure, she remarks that it is a sexless one but she presents no evidence of that nor, I believe, is there any evidence to present.

On their wedding night and in deference to her illness Horikoshi is perfectly will to sleep on his own futon, but that’s not what she wants. After asserting that “It feels like the room in spinning” Naoko invites him into her bed. Is there any doubt about what was on her mind or about what happened when the lights went out? That is only one incident in their relationship. What role does that relationship play more generally in Horikoshi’s life?

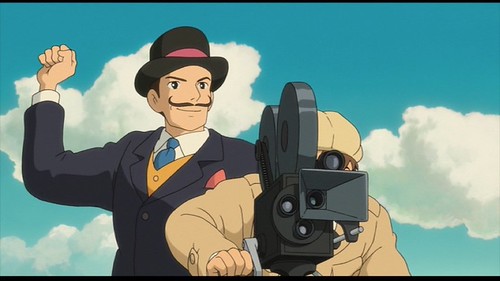

What do we see when we take the WHOLE movie into account? I don’t know, but I’m working on it [7]. In doing so we need to reflect, not only on the incidents Miyazaki offers us, but on the way that he offers them. He gives us ‘reality’ straight on. But he gives us dreams, reveries, and thoughts as well, all seamlessly arrayed before us. He even throws in a bit of film-making:

What’s that about? I don’t yet have a serious opinion. Maybe I’ll come up with one, maybe I won’t.

But it does seem to me that, not only is Miyazaki showing us a man making his way in a complex and messy world, a world which forces ugly choices on him, but he is also meditating on how it is that we order such a world in our minds. The film thus has a metaphysical character, and the nature of that metaphysics is by no means obvious. Above all the film asks us to see ourselves in Horikoshi’s world, and his world in ours. It even asks us to contemplate the role that art plays in bringing us to terms with the bottomless chaos of life.

References

[1] From “Literature as Equipment for Living”. The Philosophy of Literary Form. University of California Press: 1973, pp. 293-304. FWIW, this essay was originally published in the 30s.

[2] Hiroyuki Ota, “Hayao Miyakaki: Newest Ghibli film humanizes designer of fabled Zero”, Asahi Shimbun, August 4, 2013: http://ajw.asahi.com/article/cool_japan/movies/AJ201308040009

[3] Inkoo Kang. “The Trouble with The Wind Rises”. The Village Voice. December 11, 2013, URL: http://www.villagevoice.com/film/the-trouble-with-the-wind-rises-6440390

[4] That the pyramids were built by slaves is a widespread notion. But recent research suggests it might not be true: Jonathan Shaw. “Who Built the Pyramids?” Harvard Magazine. July-August 2003, URL: http://harvardmagazine.com/2003/07/who-built-the-pyramids-html

I have no expertise in this matter at all, and so cannot have a serious opinion about whether or not Egypt’s pyramids were built by slaves. Nor am I sure that I matters in thinking about Miyazaki’s film. What matters is what people believe to be the case. If they believe the pyramids were built by slaves – which is what I believed until I began working on the film – then that’s what will govern their thoughts about the film.

[5] Robbie Collin. “Hayao Miyazaki Interview: ‘I think the peaceful time that we are living in is coming to an end’”. The Telegraph. May 9, 2014, URL: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/film/10816014/Hayao-Miyazaki-interview-I-think-the-peaceful-time-that-we-are-living-in-is-coming-to-an-end.html

[6] Dan Sarto. “The Hayao Miyazaki Interview”. Animation World. February 14, 2014, URL: http://www.awn.com/animationworld/the-hayao-miyazaki-interview

[7] I’ve written a number of posts about the film and will be writing some more. You can find them at this URL: http://new-savanna.blogspot.com/search/label/Wind%20Rises