by Brooks Riley

Month: May 2014

The Maestà (1308-1311). Duccio da Buoninsegna. Opera Metropolitana Museum, Siena

by Sue Hubbard

Siena, a mediaeval city of windy streets, dark alleys and red roofs is one of Italy's jewels. It may now be full of school children and tourists eating ice cream as they wander amongst the stylish shops or stop to have a drink in the Piazza del Campo – which twice yearly is turned into a horse racetrack for that lunatic and partisan stampede, the Palio – but it was in the Middle Ages that Siena reached its zenith. Having been ruled by the Longobards, then the Franks, it passed into the hands of the Prince-Bishops. During the 12th century these were overthrown by Consuls who set up a secular government. It was then that Siena attained the political and economic importance that led to its rivalry with that other gilded Tuscan city, Florence. The 12th century saw the construction of many beautiful buildings: numerous towers, nobles' houses, Romanesque churches, culminating in the construction of the famous black and white duomo.

The great age of Sienese art arguably started with Duccio. No contemporary accounts of him, nor any personal documents, have survived. Though there are many records about him in municipal archives: records of changing of address, payments, civil penalties and contracts that give some idea of the life of the painter. Little is known of his painting career. Many believe he studied under Cimabue, while others think that he may have actually traveled to Constantinople and learned directly from a Byzantine master.

As a young man Duccio probably worked in Assisi, though he spent virtually his entire life in Siena. He's first mentioned in Sienese documents in 1278 in connection with commissions for 12 wooden panels for the covers of the municipal books. In 1285, a lay brotherhood in Florence commissioned him to complete an altarpiece, known now as the Rusellai Madonna, for the church of Santa Maria Novella. By that date he must already have had something of a reputation, which guaranteed the quality of his work.

The Goncourts and “Realism”

by Eric Byrd

“Called the ‘real origin' of Zola's Nana“! What 1950s drugstore customer, twirling the rack of paperbooks,

could resist that pitch? I will assume most contemporary readers are like me, and know the Goncourt brothers best by reading or rumor of their incomparable Journal. In the Journal their novels figure as neglected masterworks pillaged for themes, plots and argot by a generation of younger and more celebrated novelists – pillaged most shamelessly by Zola, who they frankly call a plagiarist. Their rancor and wounded pride made me curious, and when a copy of Germinie Lacerteux (1864) serendipitously surfaced in a dollar bin, I grabbed for it.

It's a failure, at least on the terms the Goncourts set forth in their polemical preface: they wanted to admit the lower classes into literature, via a new, scientific kind of social novel. (They diligently scouted slums and toured hospitals, between art auctions and literary dinners.) The problem is that Germinie – a lady's maid based on the Goncourts' own Rose, an irreproachable retainer of twenty-five years posthumously revealed to have stolen money and wine to fund secret sprees and support a rogue's gallery of gigolos – is dead on the page. On Germinie, the narration sounds here like a detective baldly noting the comings and goings of a mark under surveillance, there like a smug psychologist, righteous with phrenology or eugenics, composing a floridly prejudiced case history of some helpless imbecile. The Goncourts seem content to pass along maxims of human perversity, while remaining uninterested by, or incapable of, the portrayal of humans behaving perversely. They maintain a fastidious distance from scenes, from characters interacting; so much is distantly summarized; and their descriptions frequently become declamations. For all the verbosity lavished on her, Germinie is in the end hardly more vivid that her original, sketched in the Journal.

And yet Germinie Lacerteux has its pleasures, and the Goncourts their strengths. They have a genius for little misanthropic cartoons. Germinie gives everything for the sake of her lover Jupillon, an androgynous momma's boy, prole dandy and tavern idol. Jupillon is no more complex a character than Germinie, but he twitches with vile animation when touched with the Goncourts' galvanic disdain. I enjoyed reading about him. A glovemaker's boy who works in the shop window, he preens and pouts while on view; in the music halls, where he's petted and plied with drinks by fishwives and shawl-menders and depilatresses, Jopillon flaunts his “dubious elegances – hair parted in the middle, locks over his temples, wide-open shirt collars revealing his whole neck,” his sexless features “barely penciled with two moustache-strokes.” Through Jupillon – a prince, a promise of happiness to sad crones “still unused in their innermost depths, who had never been loved” – the Goncourts evoke the drabness and melancholy of the milieu through which he moves (according to his mother) “like a gentleman.”

The Only Game in Town: Digital Criticism Comes of Age

by Bill Benzon

Distant Reading and Embracing the Other

As far as I can tell, digital criticism is the only game that's producing anything really new in literary criticism. We've got data mining studies that examine 1000s of texts at once. Charts and diagrams are necessary to present results and so have become central objects of thought. And some investigators have all but begun to ask: What IS computation, anyhow? When a died-in-the-wool humanist asks that question, not out of romantic Luddite opposition, but in genuine interest and open-ended curiosity, THAT's going to lead somewhere.

While humanistic computing goes back to the early 1950s when Roberto Busa convinced IBM to fund his work on Thomas Aquinas – the Index Thomisticus came to the web in 2005 – literary computing has been a backroom operation until quite recently. Franco Moretti, a professor of comparative literature at Stanford and proprietor of its Literary Lab, is the most prominent proponent of moving humanistic computing to the front office. A recent New York Times article, Distant Reading, informs us

…the Lit Lab tackles literary problems by scientific means: hypothesis-testing, computational modeling, quantitative analysis. Similar efforts are currently proliferating under the broad rubric of “digital humanities,” but Moretti's approach is among the more radical. He advocates what he terms “distant reading”: understanding literature not by studying particular texts, but by aggregating and analyzing massive amounts of data.

Traditional literary study is confined to a small body of esteemed works, the so-called canon. Distant reading is the only way to cover all of literature.

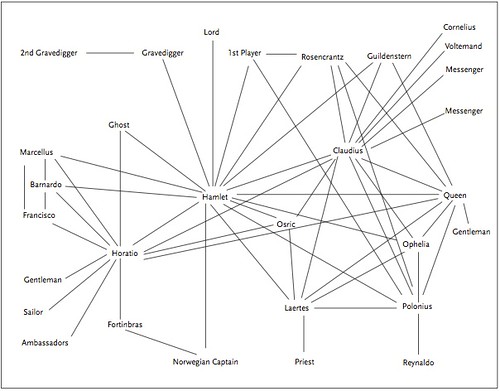

But Moretti has been also investigating drama, play by play, by creating diagrams depicting relations among the characters, such as this diagram of Hamlet:

The diagram gives a very abstracted view of the play and so is “distant” in one sense. But it also requires Moretti to attend quite closely to the play, as he sketches the diagrams himself and so must be “close” to the play.

His most recent pamphlet, “Operationalizing”: or, the Function of Measurement in Modern Literary Theory (December 2013, PDF), discusses that work and concludes by observing: “Computation has theoretical consequences—possibly, more than any other field of literary study. The time has come, to make them explicit” (p. 9).

If such an examination is to take place the profession must, as Willard McCarty asserted in his 2013 Busa Award Lecture (see below), embrace the Otherness of computing:

I want to grab on to the fear this Otherness provokes and reach through it to the otherness of the techno-scientific tradition from which computing comes. I want to recognize and identify this fear of Otherness, that is the uncanny, as for example, Sigmund Freud, Stanley Cavel, and Masahiro Mori have identified it, to argue that this Otherness is to be sought out and cultivated, not concealed, avoided, or overcome. That it's sharp opposition to our somnolence of mind is true friendship.

In a way it is odd that we, or at least the humanists among us, should regard the computer as Other, for it is entirely a creature of our imagination and craft. We made it. And in our own image.

Can the profession even imagine much less embark on such a journey?

Reasserting Russia’s literary status

Viv Groskop in the Financial Times:

Once upon a time it was the greatest literature in the world. When William Faulkner was asked to name the three best novels of all time, he cited the book Dostoevsky described as “flawless”: “Anna Karenina, Anna Karenina, Anna Karenina.”

In rankings of the world’s literary greats, Russia tends to figure more prominently than any other country. Anna Karenina, War and Peace, the stories of Anton Chekhov and Lolita (written in English and self-translated into Russian) are unfailingly on such lists, alongside Shakespeare, Proust, F Scott Fitzgerald, Mark Twain, Flaubert and George Eliot. And that’s without even mentioning Gogol, Pushkin, Turgenev, Pasternak and, of course, Dostoevsky, the writer who did down-to-earth plain-speaking just as beautifully as Tolstoy did lofty spirituality. From Notes from the Underground: “I say let the world go to hell but I should always have my tea.”

Where, though, are today’s equivalents? The question is of more than academic significance. Last December, Vladimir Putin convened a “Literary Assembly” featuring descendants of Pushkin, Dostoevsky and Tolstoy (whose great-great-grandson Vladimir is the Russian president’s cultural adviser). Putin declared that there was “a responsibility to global civilisation to preserve Russian literature” and expressed dismay that Russia could no longer boast of being “the best-read country in the world”. “Russians spend an average of only nine minutes per day reading books, and that figure is decreasing,” he said. “I think that declaring 2015 the Year of Literature in Russia is worth thinking about.”Recent events seem to have put that idea on ice.

Still, some see Russian literature as on the cusp of a recovery, pointing to the success of writers such as Mikhail Shishkin (compared to Nabokov and Chekhov) and Lyudmila Ulitskaya, the first woman to win the Russian Booker, the country’s leading prize for fiction.

More here.

Using a foreign language changes moral decisions

From Science Daily:

A new study from psychologists at the University of Chicago and Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona finds that people using a foreign language take a relatively utilitarian approach to moral dilemmas, making decisions based on assessments of what's best for the common good. That pattern holds even when the utilitarian choice would produce an emotionally difficult outcome, such as sacrificing one life so others could live.

“This discovery has important consequences for our globalized world, as many individuals make moral judgments in both native and foreign languages,” says Boaz Keysar, Professor of Psychology at UChicago. “The real world implications could include an immigrant serving as a jury member in a trial, who may approach decision-making differently than a native-English speaker.” Leading author Albert Costa, UPF psychologist adds that “deliberations at places like the United Nations, the European Union, large international corporations or investment firms can be better explained or made more predictable by this discovery.”

The researchers propose that the foreign language elicits a reduced emotional response. That provides a psychological distance from emotional concerns when making moral decisions. Previous studies from both research groups independently found a similar effect for making economic decisions.

In the new study, two experiments using the well-known “trolley dilemma” tested the hypothesis that when faced with moral choices in a foreign language, people are more likely to respond with a utilitarian approach that is less emotional.

More here. [Thanks to Ruchira Paul.]

Laser Cowboys and the Fossils of the Future

Carl Zimmer in Popular Mechanics:

One morning in November 2011, trucks were roaring down the Pan-American Highway, carrying loads of ore from mines in the Atacama Desert to the port town of Caldera, Chile. The trucks screamed past a young goateed American paleontologist named Nicholas Pyenson, who was standing at the side of the road, gazing at a 250-meter-long strip of sandstone that construction workers had cleared in preparation for building new lanes.

Pyenson, the curator of fossil marine mammals at the Smithsonian Institution, spends much of his time searching for fossils of whales. For over a year his Chilean colleague Mario Suárez had been nagging him to come to see whale fossils that had been exposed as construction workers widened the highway. Pyenson envisioned a few skull fragments wedged in a road cut—a very low priority. After completing his work at another fossil site in Chile, Pyenson finally agreed to go see the remains. And standing by the highway, he realized why Suárez had been so insistent. The road crew had uncovered not just a few whale bones but an entire whale graveyard. At least 40 prehistoric whales, some 30 feet long, were spread out before him. It would turn out to be the densest collection of fossil whales discovered anywhere in the world.

Whales may be some of the most remarkable animals in the history of life—they evolved, after all, from deerlike mammals on land and became top predators of the sea. But their fossils can be a nightmare for paleontologists. “I wouldn't wish a whale fossil on anyone,” Pyenson says. “Especially not 40.”

More here.

chatting with George Steiner

chatting with frank kermode

Vers de Société by Philip Larkin

How To Write A Classic

Mark Davie at OUPblog:

Torquato Tasso, who died in Rome on 25 April 1595, desperately wanted to write a classic. The son of a successful court poet who had been brought up on the Latin classics, he had a lifelong ambition to write the epic poem which would do for counter-reformation Italy what Virgil’s Aeneid had done for imperial Rome. From his teenage years on, he worked on drafts of a poem on the first crusade which had ‘liberated’ Jerusalem from its Muslim rulers in 1099, a subject which he deemed appropriate for a Christian epic. His ambition reflected the climate in which he grew up: his formative years (he was born in 1544) saw a newly assertive orthodoxy both in literary theory (dominated by Aristotle’s Poetics, published in a Latin translation in 1536) and in religion (the Council of Trent, convened to meet the challenge of Luther’s revolt, was in session intermittently between 1545 and 1563). Those who saw Aristotle’s text as normative insisted that an epic must deal with a single historical theme in a uniformly elevated style, while the decrees emanating from Trent re-asserted the authority of the church and took an increasingly hard line against heresy. As he worked on his poem, Tasso was nervously anxious not to offend either of these constituencies…

Some of Tasso’s drafts had leaked out during the poem’s long gestation and had been published without his consent, so the poem was eagerly awaited, and it immediately had its devotees. Not everyone, however, was impressed. Among those who were not was Galileo, who wrote a series of acerbic notes on the poem some time before 1609. His criticisms are mostly on details of language and style, but in one revealing comment he compares Tasso’s poetic conceits to ostentatiously difficult dance steps, which are pleasing only if they are ‘carried through with supreme accomplishment, so that their gracefulness overrides their affectation’. Grazia versus affettazione: the terms are taken from Castiglione’s Book of the Courtier, that indispensable guide to Renaissance manners which decreed that the courtier’s accomplishments should be displayed with an appearance of effortless nonchalance. Tasso’s offence against courtly manners was that he tried too hard.

Read the rest here.

Immortality through advanced technology and primitive diet

Charlotte Allen in The Weekly Standard:

Aubrey de Grey, 51, is the man who insists that within a few decades technology will enable us human beings to beat death and live forever. Actually, he’s not the only one to make these assertions—that death is a problem to be solved, not a fate to be endured—but he is the only one I know of to give eternal life an exciting, just-around-the-corner timeline. “Someone is alive right now who is going to live to be 1,000 years old,” he told me when I interviewed him last fall at the SENS (for “Strategically Engineered Negligible Senescence”) Research Foundation headquarters, a well-worn 3,000-square-foot cement building in the Silicon Valley flatlands where de Grey holds the title of chief science officer. He has made this prophecy to a number of reporters—and this is what makes de Grey the most famous of a growing number of people who have staked their lifestyles and futures on the prospect of never dying. He is constantly interviewed by the press, has written a 2007 book, Ending Aging, and has given at least two of the TED talks that are a genius-certification ritual for public intellectuals these days.

…De Grey subscribes to the reigning theory of the live-forever movement: that aging, the process by which living things ultimately wear themselves out and die, isn’t an inevitable part of the human condition. Instead, aging is just another disease, not really different in kind from any of the other serious ailments, such as heart failure or cancer, that kill us. And as with other diseases, de Grey believes that aging has a cure or series of cures that scientists will eventually discover. “Aging is a side effect of being alive,” he said during our interview. “The human body is exactly the same as a car or an airplane. It’s a machine, and any machine, if you run it, will effect changes on itself that require repairs. Living systems have a great deal of capacity for self-repair, but over time some of those changes only accumulate very slowly, so we don’t notice them until we are very old.”

More here.

The making of a Marx: The life of Eleanor Marx

Rachel Holmes in The Independent:

When I set out to write the life of Eleanor Marx in 2006 some friends worried that yet again I’d been seduced by an unfashionable and overly abstruse biographical subject. Either that, or they just said: “Who?” A Marx? The mother of socialist feminism? It didn’t sound catchy in our new century. Yet Eleanor Marx is one of British history’s great heroes. Born in 1855 in a Soho garret to hard up German immigrant exiles, her arrival was initially a disappointment to her father. He wanted a boy. By her first birthday Eleanor had become his favourite. She was nicknamed Tussy, to rhyme, her parents said, with “pussy” not “fussy”. Cats she adored; fussy she wasn’t. She loved Shakespeare, Ibsen, both the Shelleys, good poetry, bad puns and champagne. She would be delighted to know that we can claim her as the first self-avowed champagne socialist. Yet during the journey of writing the life of Eleanor Marx I discovered that I was writing about an increasingly topical subject. Friends sent me articles about the resurgence in the reading of the primary work of Marx and Engels amongst the under-50s, particularly in countries where there are currently new movements for social democracy. Then, Harvard University Press published the French economist Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century on the subject of economic inequality. Since its release last month, Piketty’s Capital has sold nearly 80,000 copies. This would much amuse Eleanor Marx, who knew how disappointed her father was when the first volume of his Capital was published in 1867 to resounding silence and negligible sales. She spent a large part of her life editing and translating this and subsequent volumes of the work whose distribution outran that of the Bible and Shakespeare in the 20th century.

What started for Karl Marx as a 30- to 50-page essay, developed into a life’s work that his youngest daughter inherited. She sat on her father’s knee, played around him and learned to write and draw by his side at the kitchen table, where he worked in the early years of the project. Tussy and Capital grew up together. Marx said: “Tussy is me.” Her life and character form an epic story of adventure, morality, dilemma, contradiction and tragedy. Her thoughts and actions embody Britain’s history of struggle to achieve social democracy and equality.

More here.

Sunday Poem

Lust

If only he could touch her,

Her name like an old wish

In the stopped weather of salt

On a snail. He longs to be

Words, juicy as passionfruit

On her tongue. He’d do anything,

Would dance three days & nights

To make the most terrible gods

Rise out of ashes of the yew,

To step from the naked

Fray, to be as tender

As meat imagined off

The bluegill’s pearlish

Bones. He longs to be

An orange, to feel fingernails

Run a seam through him.

Yusef Komunyakaa

from Poetry, Vol. 175, No. 1, October/November

publisher: Poetry, Chicago, 1999

‘Congo: The Epic History of a People’

J. M. Ledgard at The New York Times:

On June 5, 1978, the Congolese dictator Joseph-Désiré Mobutu stood on a hot grassy bluff in the south of his vast country — then named Zaire — and watched as the engines on a space rocket ignited. “Slowly, the rocket rose from the launching pad. A hundred kilometers into the atmosphere, that’s where it was headed, a new step forward in African space travel.” After a few moments, though, “the rocket listed, cut a neat arc to the left and landed a few hundred meters away, in the valley of the Luvua, where it exploded.” For David Van Reybrouck the rocket represents Mobutu’s regime: “A parabola of soot. . . . After the steep rise of the first years, his Zaire toppled inexorably and plunged straight into the abyss.”

Watching the failed rocket launch on YouTube is both Pythonesque and distressing. How did the West German space company Otrag get absolute control of an area of Congo the size of Iceland? Imagine if Mobutu’s state had been better run, not just that Congo had become a launchpad for interstellar travel, but that it had been able to project a stabilizing influence on neighboring Rwanda, heading off the 1994 genocide there.

more here.

how the Higgs particle was found

Graham Farmelo at The Guardian:

To find the Higgs – or to rule out its existence – was one of the aims of the Large Hadron Collider, a huge machine that accelerates protons (sub-nuclear particles) to within a squillionth of the speed of light before smashing them together (hence the book's title). If the particle existed, it should have quickly fallen apart into other particles in ways that experimenters could study. This is much easier said than done: as Butterworth explains, it was always going to be extremely difficult to pin down the particle, as the evidence was expected to be largely – but not completely – obscured by huge numbers of tracks due to other subatomic processes. Several months after the collider was switched on, there was no clear sign of the particle, leading some theoreticians to get cold feet and even to doubt its existence.

Butterworth tells the story of how the particle was eventually tracked down, making clear the extent of the challenge. He is an engaging guide, generous to all his colleagues, especially in the media – “We should be more forgiving of some of the excitable headlines” – but is sometimes a tad harsh on theoreticians.

more here.

A monumental study of the globalising age that was the 19th century

David Cannadine at The Financial Times:

From one perspective, attempts to write panoramic, all-encompassing accounts of humanity are nothing new. On the contrary, they have been around for a very long time. One early example was Sir Walter Raleigh’s The History of the World, published exactly 400 years ago while its author was languishing as a prisoner in the Tower of London. Yet despite its million words, Raleigh took his story only from the creation down to the Ancient Greeks and Romans, and since he died in 1618, he never even got to the birth of Jesus Christ.

More recent practitioners of the genre include HG Wells, whose The Outline of History (1920) provided a single narrative extending from the origins of the earth to the first world war. Professional historians did not like it, but Wells’s book was a popular success, and it was remarkably free of the Eurocentric and racist attitudes much in evidence at the time. On a very different scale was Arnold Toynbee’s A Study of History, which appeared in 12 vast volumes between 1934 and 1961, and which chronicled the rise and fall of the many separate civilisations that Toynbee believed divided the past. Once again, the scholarly fraternity disapproved, and it is only recently that such broad-based approaches to the long, varied, dispersed and yet also joined-up story of humanity have acquired serious academic credibility.

more here.

Where Have All The Workers Gone

Cait Murphy in Inc. Magazine:

But try running a 95-year-old electronics connector manufacturer in the threesquare-mile Westchester County village. Or hiring for it. There are almost certainly more hedge-fund managers in Mount Kisco than there are tool and die makers—and Gretchen Zierick has no use for the Wall-Streeters. But she says she can’t even get the time to talk with students about manufacturing careers, because, well, every kid is above average, as Garrison Keillor would say, and supposed to go to college. “There just aren’t people out there with the skills we need, or the interest in acquiring them,” says the president of Zierick Manufacturing Corporation. She’s begun an informal apprenticeship, contacted a local community college, and is working with temp agencies. Even so, she’s short three tool and die makers.

What’s a 60-employee family-owned company to do?

Join the club, Gretchen Zierick. Business owners everywhere, it seems, complain they can’t find good help these days. It’s a staple of conversation from talk radio to chats over the donuts and coffee at Chamber meetings.

That concern is reflected in numerous recent surveys of businesses—big and small. Almost four in 10 U.S. employers told Manpower, a staffing company, that they were having difficulty filling jobs. The feeling is particularly acute at small and midsize companies. In a U.S. Chamber of Commerce study, 53 percent of leaders at smaller businesses said they faced a “very or fairly major challenge in recruiting nonmanagerial employees.”

And in a survey of Inc. 5000 CEOs last year, 76 percent said that finding qualified people was a major problem.

What’s really interesting about all this is that it’s not just the usual suspects who are complaining about the lack of good workers. You know: software companies that want to hire programmers from India. It turns out that good old manufacturers are having trouble finding excellent employees.

So, what is going on? And why is this happening?

Read the rest here.

The novel is dead (this time it’s for real)

Literary fiction used to be central to the culture. No more: in the digital age, not only is the physical book in decline, but the very idea of 'difficult' reading is being challenged. The future of the serious novel, argues Will Self, is as a specialised interest.

Will Self in The Guardian:

If you happen to be a writer, one of the great benisons of having children is that your personal culture-mine is equipped with its own canaries. As you tunnel on relentlessly into the future, these little harbingers either choke on the noxious gases released by the extraction of decadence, or they thrive in the clean air of what we might call progress. A few months ago, one of my canaries, who's in his mid-teens and harbours a laudable ambition to be the world's greatest ever rock musician, was messing about on his electric guitar. Breaking off from a particularly jagged and angry riff, he launched into an equally jagged diatribe, the gist of which was already familiar to me: everything in popular music had been done before, and usually those who'd done it first had done it best. Besides, the instant availability of almost everything that had ever been done stifled his creativity, and made him feel it was all hopeless.

A miner, if he has any sense, treats his canary well, so I began gently remonstrating with him. Yes, I said, it's true that the web and the internet have created a permanent Now, eliminating our sense of musical eras; it's also the case that the queered demographics of our longer-living, lower-birthing population means that the middle-aged squat on top of the pyramid of endeavour, crushing the young with our nostalgic tastes. What's more, the decimation of the revenue streams once generated by analogues of recorded music have put paid to many a musician's income. But my canary had to appreciate this: if you took the long view, the advent of the 78rpm shellac disc had also been a disaster for musicians who in the teens and 20s of the last century made their daily bread by live performance. I repeated one of my favourite anecdotes: when the first wax cylinder recording of Feodor Chaliapin singing “The Song of the Volga Boatmen“ was played, its listeners, despite a lowness of fidelity that would seem laughable to us (imagine a man holding forth from a giant bowl of snapping, crackling and popping Rice Krispies), were nonetheless convinced the portly Russian must be in the room, and searched behind drapes and underneath chaise longues for him.

So recorded sound blew away the nimbus of authenticity surrounding live performers – but it did worse things. My canaries have often heard me tell how back in the 1970s heyday of the pop charts, all you needed was a writing credit on some loathsome chirpy-chirpy-cheep-cheeping ditty in order to spend the rest of your born days lying by a guitar-shaped pool in the Hollywood Hills hoovering up cocaine.

More here.

The Origin of Ideology

Chris Mooney in Washington Monthly:

If you want one experiment that perfectly captures what science is learning about the deep-seated differences between liberals and conservatives, you need go no further than BeanFest. It’s a simple learning video game in which the player is presented with a variety of cartoon beans in different shapes and sizes, with different numbers of dots on them. When each new type of bean is presented, the player must choose whether or not to accept it—without knowing, in advance, what will happen. You see, some beans give you points, while others take them away. But you can’t know until you try them.

In a recent experiment by psychologists Russell Fazio and Natalie Shook, a group of self-identified liberals and conservatives played BeanFest. And their strategies of play tended to be quite different. Liberals tried out all sorts of beans. They racked up big point gains as a result, but also big point losses—and they learned a lot about different kinds of beans and what they did. Conservatives, though, tended to play more defensively. They tested out fewer beans. They were risk averse, losing less but also gathering less information.

One reason this is a telling experiment is that it’s very hard to argue that playing BeanFest has anything directly to do with politics. It’s difficult to imagine, for example, that results like these are confounded or contaminated by subtle cues or extraneous factors that push liberals and conservatives to play the game differently. In the experiment, they simply sit down in front of a game—an incredibly simple game—and play. So the ensuing differences in strategy very likely reflect differences in who’s playing.

The BeanFest experiment is just one of dozens summarized in two new additions to the growing science-of-politics book genre: Predisposed: Liberals, Conservatives, and the Biology of Political Differences, by political scientists John R. Hibbing, Kevin B. Smith, and John R. Alford, and Our Political Nature, by evolutionary anthropologist Avi Tuschman. The two books agree almost perfectly on what science is now finding about the psychological, biological, and even genetic differences between those who opt for the political left and those who tilt toward the right.

More here.