Sahabzada Yaqub Khan is the father of one of my closest friends, Samad Khan. He is also probably the most remarkable man I have ever met. All Pakistanis know who he is, as do many others, especially world leaders and diplomats, but to those of you for whom his name is new, I would like to take this Monday Musing as an opportunity to introduce him.

Sahabzada Yaqub Khan is the father of one of my closest friends, Samad Khan. He is also probably the most remarkable man I have ever met. All Pakistanis know who he is, as do many others, especially world leaders and diplomats, but to those of you for whom his name is new, I would like to take this Monday Musing as an opportunity to introduce him.

The first time that I met Sahabzada Yaqub Khan about six years ago, he was in Washington and New York as part of a tour of four or five countries (America, Russia, China, Japan, etc.) relations with which are especially important to Pakistan. He had come as President Musharraf‘s special envoy to reassure these governments in the wake of the fall of the kleptocratic shambles that was Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif‘s so-called democratic government. Samad Khan, or Sammy K as he is affectionately known to friends, invited me over to his apartment to meet his Dad. I had heard and read much about Sahabzada Yaqub and knew his reputation for fierce intellect and even more intimidating, had heard reports of his impatience with and inability to suffer fools, so I was nervous when I walked in. Over the next couple of hours I was blown away: Sahabzada Yaqub was not much interested in talking about politics, and instead, asked about my doctoral studies in philosophy. It was soon apparent that he had read widely and deeply in the subject, and knew quite a bit about the Anglo-American analytic philosophy I had spent the previous five years reading. He even asked some pointed questions about aspects of philosophy which even some graduate students in the field might not know about, much less laymen. Though we were interrupted by a series of phone calls from the likes of Henry Kissinger wanting to pay their respects while Sahabzada Yaqub was in town, we managed to talk not just about philosophy, but also physics (he wanted to know more about string theory), Goethe (SYK explained some of his little-known scientific work, in addition to quoting and then explicating some difficult passages from Faust), the implications of Gödel’s incompleteness theorem, and Urdu literature, of which Sahabzada Yaqub has been a lifelong devotee.

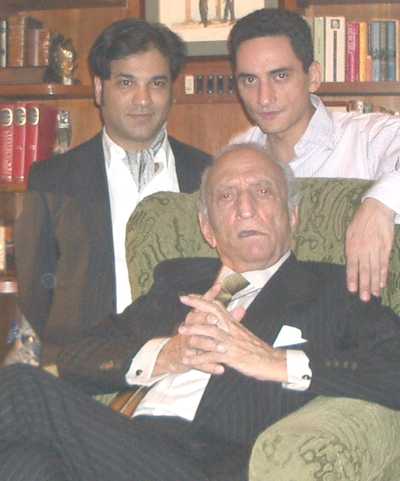

I left late that night dazzled by his brilliance, and elated by his warmth and generosity. Sahabzada Yaqub listens more than he speaks, but when he does speak, he is a raconteur extraordinaire. Since then, I have been fortunate enough to get to know him well, and have spent many a rapt hour in his company. On my last trip to Islamabad, he and his wife and Sammy K had me and my wife Margit over for dinner, where upon learning that Margit is from Italy, Sahabzada Yaqub spoke with her in Italian. Then, realizing that she is from the South Tyrol (the German-speaking part of Italy near the Austrian border), he spoke to her in German, giving us a fascinating mini-lecture on German translations of Shakespeare. I can picture him now, emphatically declaiming “Sein oder nicht sein. Das ist hier die frage.” (The picture on the right with Sammy K and me is from that night.)

I left late that night dazzled by his brilliance, and elated by his warmth and generosity. Sahabzada Yaqub listens more than he speaks, but when he does speak, he is a raconteur extraordinaire. Since then, I have been fortunate enough to get to know him well, and have spent many a rapt hour in his company. On my last trip to Islamabad, he and his wife and Sammy K had me and my wife Margit over for dinner, where upon learning that Margit is from Italy, Sahabzada Yaqub spoke with her in Italian. Then, realizing that she is from the South Tyrol (the German-speaking part of Italy near the Austrian border), he spoke to her in German, giving us a fascinating mini-lecture on German translations of Shakespeare. I can picture him now, emphatically declaiming “Sein oder nicht sein. Das ist hier die frage.” (The picture on the right with Sammy K and me is from that night.)

Sahabzada Yaqub Khan has done and been so many things, that it is hard to know where to begin describing his career in the short space that I have. An aristocrat from the royal family of Rampur, he has served as a soldier, statesman, diplomat, and chairman of the board of trustees of Pakistan’s finest university, among other things, and has excelled in each of these roles.  In 1970, he was a Lieutenant General in the Pakistan army, and governor of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) when he was ordered by the military dictator of Pakistan at the time, General Yahya Khan, to have troops forcibly put down the mutiny there, which had spilled out into the streets. It is a testament to Sahabzada Yaqub’s moral courage that he refused, and resigned instead. Yahya, of course, found less-conscientious generals to do his dirty work, and the result was a massacre of Bengali civilians before a humiliating defeat in war when India stepped in on the side of the insurgents, and ultimately the dismemberment of Pakistan. This is a dark chapter in Pakistani history for which the government has yet to apologize to the Bangladeshi people. Sahabzada Yaqub Khan is, however, still celebrated as a hero in Bangladesh. (His moral convictions haven’t changed, either. The last time Sahabzada Yaqub visited New York in July, 2004 he came over for drinks and pizza–he is a man of sophisticated tastes who still enjoys simple things–and more than anything else, that day he repeatedly expressed his shock and dismay at the behavior of U.S. soldiers at Abu Ghraib. What particularly galled and appalled him was that the troops took such delight and pride in their torturous abuse that they felt compelled to record it on film–as if they wanted to be able to relive it. The lack of shame was what disturbed him the most.)

In 1970, he was a Lieutenant General in the Pakistan army, and governor of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) when he was ordered by the military dictator of Pakistan at the time, General Yahya Khan, to have troops forcibly put down the mutiny there, which had spilled out into the streets. It is a testament to Sahabzada Yaqub’s moral courage that he refused, and resigned instead. Yahya, of course, found less-conscientious generals to do his dirty work, and the result was a massacre of Bengali civilians before a humiliating defeat in war when India stepped in on the side of the insurgents, and ultimately the dismemberment of Pakistan. This is a dark chapter in Pakistani history for which the government has yet to apologize to the Bangladeshi people. Sahabzada Yaqub Khan is, however, still celebrated as a hero in Bangladesh. (His moral convictions haven’t changed, either. The last time Sahabzada Yaqub visited New York in July, 2004 he came over for drinks and pizza–he is a man of sophisticated tastes who still enjoys simple things–and more than anything else, that day he repeatedly expressed his shock and dismay at the behavior of U.S. soldiers at Abu Ghraib. What particularly galled and appalled him was that the troops took such delight and pride in their torturous abuse that they felt compelled to record it on film–as if they wanted to be able to relive it. The lack of shame was what disturbed him the most.)

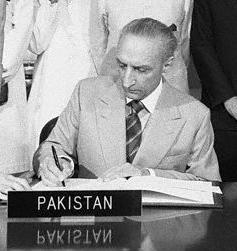

Soon after the debacle of 1971, when a properly-elected civilian government had taken power in Pakistan, Sahabzada Yaqub was offered, and accepted, several diplomatic appointments, serving as Pakistan’s ambassador to France, the Soviet Union, and the United States. Let me illustrate his reputation as a cold-war strategist with a quick anecdote: one day Sammy K and I were searching through some old packed boxes of Sammy K’s for a 70s punk rock record, when I came upon an official looking document, with the seal of the President of the United States on it. On examination, it turned out to be a letter from Nixon to Sahabzada Yaqub, written while Nixon was president, and (I am quoting from memory) this is roughly what Nixon had to say: “It was a pleasure meeting you and spending some time talking to you. Alexander Haig had told me that you are probably the most astute geopolitical thinker alive today. Having met you, I believe this was an understatement. Call me anytime.” Or words to that effect.

Soon after the debacle of 1971, when a properly-elected civilian government had taken power in Pakistan, Sahabzada Yaqub was offered, and accepted, several diplomatic appointments, serving as Pakistan’s ambassador to France, the Soviet Union, and the United States. Let me illustrate his reputation as a cold-war strategist with a quick anecdote: one day Sammy K and I were searching through some old packed boxes of Sammy K’s for a 70s punk rock record, when I came upon an official looking document, with the seal of the President of the United States on it. On examination, it turned out to be a letter from Nixon to Sahabzada Yaqub, written while Nixon was president, and (I am quoting from memory) this is roughly what Nixon had to say: “It was a pleasure meeting you and spending some time talking to you. Alexander Haig had told me that you are probably the most astute geopolitical thinker alive today. Having met you, I believe this was an understatement. Call me anytime.” Or words to that effect.

From 1982 onwards, Sahabzada Yaqub Khan served as Pakistan’s foreign minister in various governments. He was a central figure in the UN negotiations to end Soviet involvement in Afghanistan. From 1992 to 1994, Sahabzada Yaqub was also the United Nations Secretary General’s Special Representative for the Western Sahara. And in November 1999, as I have already mentioned, Sahabzada Yaqub traveled to various countries as President Musharraf’s special envoy. While Sahabzada Yaqub was in America as part of that tour, William Safire wrote an editorial in the New York Times in which, amongst much else, he said that for clarification about the situation in Pakistan he turned to “the most skillful diplomat in the world today: Sahabzada Yaqub Khan.”

Though he has always been fiercely protective of his privacy, politely refusing to write his memoirs despite great public demand (including entreaties over the last few years from me), Sahabzada Yaqub Khan has recently allowed some of his writings to be collected into book form: Strategy, Diplomacy, Humanity, compiled and edited by Dr. Anwar Dil, had its launch earlier this month at a ceremony at the Agha Khan University in Karachi. Here is a description of the book from the AKU website:

Though he has always been fiercely protective of his privacy, politely refusing to write his memoirs despite great public demand (including entreaties over the last few years from me), Sahabzada Yaqub Khan has recently allowed some of his writings to be collected into book form: Strategy, Diplomacy, Humanity, compiled and edited by Dr. Anwar Dil, had its launch earlier this month at a ceremony at the Agha Khan University in Karachi. Here is a description of the book from the AKU website:

…the book Strategy, Diplomacy, Humanity contains Sahabzada Yaqub-Khan’s selected writings, with photos spanning his entire life, culled from his lectures, articles and speeches between 1980s and the present day. They describe his thoughts on national strategy, diplomacy, world affairs, education and his vision of a world of dialogue and peace for all of humanity. In the foreword, Shaharyar M. Khan, former foreign secretary of Pakistan, describes the book as “essential reading for the student of modern history, diplomatic strategy, and the art and craft of negotiations. They reflect the outpourings of a brilliant analyst whose immense talent was applied towards achieving pragmatic objectives in Pakistan’s national interest.”

I have been unable to obtain the book, but even without having seen it yet, I can safely urge you to get a copy and read it if you can. I also hope that Sahabzada Yaqub overcomes his reticence soon and writes the detailed memoirs that history demands of him.

Among other things, Sahabzada Yaqub Khan is a true polyglot: he can speak, read and write somewhere between 6 and 10 languages. While he was governor of East Pakistan, he learned Bengali and delivered public addresses in it, which went a long way toward assuaging their concerns of cultural dominance by West Pakistan. He is also a stylishly impeccable dresser (he was voted best-dressed several years in a row by the Washington diplomatic corps). My greatest joy in his company, however, remains his inimitable explications of the deeper philosophical implications buried in Ghalib‘s couplets, of which he has been a longtime and enthusiastic student. In short, he is a man with many and diverse qualities.

Have a good week!

My other recent Monday Musings:

Special Relativity Turns 100

Vladimir Nabokov, Lepidopterist

Stevinus, Galileo, and Thought Experiments

Cake Theory and Sri Lanka’s President