Jamie is a young man in his early twenties. He has Down syndrome and is the son of Michael Bérubé and Janet Lyon, who teach at Penn State. Michael has just published Life as Jamie Knows It: An Exceptional Child Grows Up (Beacon 2016). Here’s how Michael characterizes his book (p. 16):

In the following pages, Jamie and I will tell you about his experiences at school, his evolving relationship with his brother, his demeanor in sickness and health, and his career as a Special Olympics athlete. And we’ll tangle with bioethics, politicians, philosophers, and a wide array of people we believe to be mistaken about some very important questions, such as whether life is worth living with a significant disability and whether it would be better for all the world if we could cure Down syndrome. (Quick preview: Yes. No.) But we will not tell you that Jamie is a sweet angel/cherub whose plucky triumphs over disability inspire us all. We will not tell you that special-needs children are gifts sent to special parents. And we will definitely not tell you that God never gives someone more than he or she can handle, because as a matter of fact, God dos that all the time–whether through malice or incompetence I cannot say.

That’s a fair characterization of the book. There are stories about Jamie, lots of them, and some stories by Jamie in the Afterword. But there is also philosophy, especially the final chapter, and discussions of disability policy, health care, education, and job-related. The stories about Jamie, his family, and friends, both illuminate and motivate the more abstract discussions. Here and there, as you might already have deduced, Michael slips in a zinger, sometimes mild, sometimes hot and spicy.

In the interests of full disclosure I should tell you that Michael is a friend. While I’ve only seen him face-to-face once, I’ve known him online for sometime, interacting with him through his now defunct blog, American Airspace, where Jamie was a frequent topic of conversation, and through email about this and that, mostly recently about Jamie’s art – a topic we’ll get to in due course. Thus this is not an arms-length review. It is simply a discussion of issues raised by a thought-provoking and well-written book.

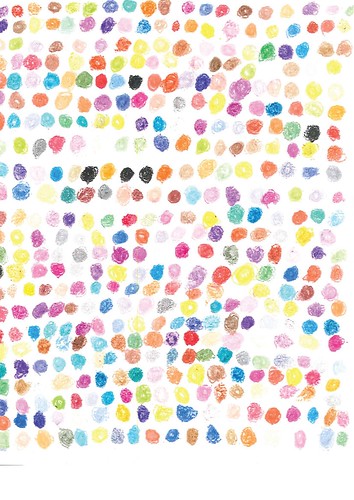

Dots in Rhythm

The book first hit home for me with this passage (66):

Some of the people on Medicare and Medicaid and Supplemental Security Income are people with disabilities. Your parents, your cousins, your grand-nephews, your neighbors–some of them are people with disabilities. They have autism or Alzheimer’s or arthritis or achondroplasia or carpal tunnel syndrome of Crohn’s disease or Parkinson’s or Huntington’s or cerebral palsy or MS or traumatic brain injury; they are deaf or blind or paraplegic or schizophrenic.

A high school friend was hemophilic. Family friends, father and then son, had Parkinson’s. My father’s father was blind; he had once been a photographer and wood carver. My mother had Alzheimer’s.

Most of the specific conditions Michael lists have a genetic component, though not all (e.g. traumatic brain injury). Some are manifest at or soon after birth (e.g. Down syndrome, autism) while others don’t show up until later in life (e.g. Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s). If the condition is present at birth, then it is a determining factor in a person’s identity as they mature and build a life. If the condition shows up later, then it may well degrade or even destroy their identity. That is true whether the condition has a genetic component or is the result of severe injury or disease.

This plays into discussions of just how we conceptualize Down syndrome: disease or disability? Disease is the result of a condition that is not inherent in the diseased individual. Diseases may result in permanent disability, but not necessarily so. In these discussions the default understanding of “disability” is inherent disability, such as we see with autism. Deafness may be an inherent disability or it may be the result of disease or injury; blindness is the same. Diseases can be cured and eliminated; inherent disabilities cannot, though the fetus can be aborted if the disability is detected. Disabilities, however, can be mitigated accommodations in healthcare, education, transportation, workplace, and so forth. Diseases imply a research and treatment agendas that are quite different from disabilities.

Michael, as you might surmise, regards Down syndrome as an inherent disability. It won’t be cured. But we can mitigate the consequences of Down syndrome by providing appropriate help to individuals and families throughout life. Above all, as we have learned in the last two or three decades, people with Down syndrome can live far richer lives than had been thought possible when they were labeled “Mongoloid idiots” and had a life expectancy of less than 25 years. If we expect more of them, give them room, and support them in their efforts, they will grow and live into middle age.

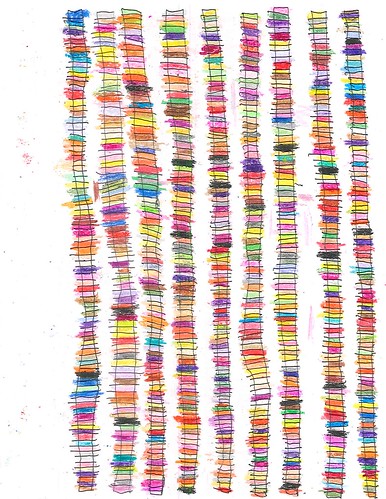

Towers of Color

Thus Jamie has become a traveler. Michael travels frequently on academic business of one kind or another and takes Jamie with him. Jamie doesn’t have to book the plain tickets or the hotel rooms, much less pay for it all, but he has proven to be an alert and engaging travel companion. He’s been to Pittsburg, New York City, Las Vegas, Rome, Florence, and who knows where else. Making lists, swimming in pools, visiting museums, going to shows, listening patiently while his father delivers a lecture, and sometimes participating in the lecture when the topic is disability. On one occasion he upstaged the old man by concluding his portion of the program, not with “thank you” but with “merci beaucoup” (81).

In the Special Olympics Jamie learned to upstage himself. It was in April of 2009 at a meet in central Pennsylvania. He won gold in the 25m and 50m freestyle and was then placed in a 25m backstroke heat where he seemed hopelessly outclassed by two adult swimmers whose qualifying times were 10 seconds better than his. And yet, much to Michael’s amazement and satisfaction, he won. It seems that, when in midrace Jamie surveyed the field, he realized he was losing and went into overdrive, “churning his arms and legs frantically to beat his fellow swimmers” (120). He also beat is own personal best by over ten seconds.

And then there’s horse-back riding, martial arts, and golf, where Jamie displays a calm and composure at odds with the frustration inherent in a game where one tries to put a small ball into a somewhat larger hole over distances measured in 100s of yards. But the world of sports is not the real world; it is a world apart.

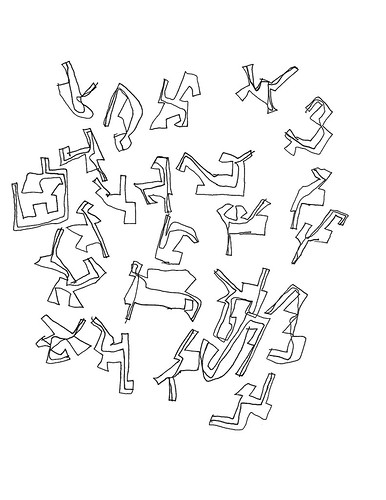

Biomorphic Objects

As is the world of the arts. Jamie loves both the visual arts and music and both figure in his prodigious list-making – Michael has a number of Jamie’s lists posted on line, and not just those of musicians and artists, but also lists of counties in Pennsylvania, military leaders, dates, wrestling matches by The Undertaker, capital cities of countries I’ve never heard of, and other topics. He’s visited many art museums and has a particular fondness for Caravaggio and the Beatles. What Michael doesn’t discuss in the book, however, is the fact that Jamie himself is an artist. But he has placed an extensive sample of Jamie’s work online and I’ve spent a good deal of time over the past week examining it and have become convinced that his investigations merit that label, “investigation.” He is exploring and discovering and, I rather imagine, have a great deal of fun as well.

He has settled on a few themes and motifs and has covered countless sheets of paper with them. Jamie has no interest in figurative art; all his work is abstract. You see some examples of them in this post.

I suspect that is because the relationship between what you see on the page, as an artist, and what you do as you draw is quite direct in the case of abstract art, but oddly remote for figurative art. While natural scenes often have a complexity that is easily avoided in abstract imagery, that is not, I suspect, the primary problem. The primary problem is that the world exists in three dimensions while drawing surfaces have only two dimensions. Figuring out how to project the 3D world into a 2D surface is difficult, so difficult that artists have at times taken to mechanical means, such as the camera obscura, a pinhole device used to project a scene onto a flat surface where the artist can then simply trace the image. Some years ago David Hockney caused a minor scandal in the art world when he suggested that the some of the old masters used mechanical aids, such as the camera obscura, rather than drawing guided only by the unaided eye.

But that’s a digression. The point is simply that figuring out how to place a line on a flat surface so that it accurately traces the outline of what one sees, that is a very difficult thing to do, so difficult that many artistic traditions have simply ignored the problem. By choosing to work only with abstract imagery, Jamie sidesteps that problem. He has chosen to work with round dots, concentric bands, rectangular towers and cells, and intriguingly biomorphic geometric objects. While that is a limitation, we should note that many fine artists have opted for abstraction over the last century and that a major family of aesthetic traditions, those is many Islamic nations, have eschewed representational art (as sacrilegious) and developed rich traditions of calligraphy and geometric patterning.

I note Jamie’s use of color and rhythm in the dots and the towers images (first two in this post) and dynamic quality of his biomorphic images (third in this post). But this is not the place for a detailed discussion of Jamie’s art – I’ve already done that in a series of blog posts. The general point is simply that Jamie has chosen materials he is comfortable with and has thrived from doing so.

What of others with Down syndrome? The late Judith Scott had Down syndrome and she achieved international acclaim as a fiber artist. Michael informs me, however, that he doesn’t know of anyone else with Down syndrome who draws as extensively as Jamie does. Is Jamie’s level of artistic skill that rare among those with Down syndrome? I certainly have no way of knowing.

What would happen if children with Down syndrome were exposed to Jamie’s art, perhaps even watch him doing it (most likely through video or film)? Would they imitate him and develop their own preferred motifs and themes? Could people be trained to teach the Jamie method?

Concentric Bands

Perhaps the main disappointment in Jamie’s life is that he hasn’t been able to obtain satisfactory employment. His job skills, obviously, are limited. He’s had various part-time jobs, some better, much better in fact, than others. He currently works four hours on Fridays cataloging books and tracking inventory at Penn State Press, a job he likes very much. But it’s only four hours a week.

Michael observes (166):

that some people with disabilities were disabled by modernity, insofar as the organization of life and work in modern societies gave them fewer roles in public life than they might have had in some premodern societies. The Industrial Revolution increased the aggregate quality of life for the people of developed countries, but it also maimed millions of workers – men, women, and children – and inaugurated the era of the mental institution and the sciences of population management.

But Michael is not waxing nostalgic for the Good Old Days. He’s just pointing out that modernity is not an unalloyed good and that disability is somewhat contextual. He notes that his vision problem would have been irrelevant in a world without writing; and I note that dyslexia is a disabling condition that is actually defined with respect to writing. There was no dyslexia 6000 years ago.

What of the future? Are we on the brink of knowledge that will allow us to eliminate inherent disabilities or even milder conditions through genetic manipulation? Perhaps, and perhaps not. As Michael notes (182-83):

[Glenn] Treisman’s talk swiftly and decisively put to rest the claims of “liberal eugenics,” point out not only that we have no idea how to go about eliminating things like shyness or laziness but also, and more importantly, that we have no idea whether some of the traits we now consider undesirable or harmful actually have survival value for us as a species. In other words, for all we know, our capacity for depression is what is what got us through the Pleistocene. Likewise, for all we know, shyness and laziness are, in evolutionary terms, two of our saving graces.

There’s a lot we don’t know, and much of that ignorance is but the other side of knowledge we’ve only come by quite recently.

It is only recently that we’ve had the knowledge and technique to create powerful computers. And now those computers are putting people out of work, just as steam engines, electric motors, and a host of other devices did over the last two centuries. Will our computing machines disable us all? I suspect not, but something rather like it is a real question.

What those machines can do now is both interesting enough and threatening enough to force us to reconsider who and what we are. At the same time psychologists and biologists have been learning more about the minds and feeling of animals and they’re looking more and more like us every day. What happens to human identity in the age of intelligent machines and socially adept animals?

Well, Jamie Bérubé is right in there, forcing us to think about who we are. For that ultimately is where Life as Jamie Knows It leads us. Coming to terms with Jamie’s life forces us to come to terms with our own.

In the annoying manner of math texts, however, I’ll leave it as an exercise to the reader to continue that line of thought. I want to finish this discussion by turning things around and letting Jamie have the last word. But first Michael has some explaining to do:

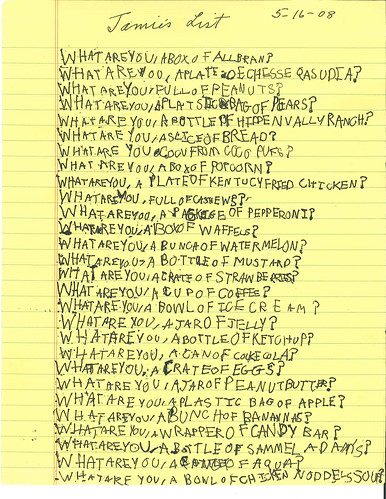

OK, so this routine began in March 2007, when Jamie and I were in Florida and I was speaking at Stetson University in DeLand. (We then took a couple of days’ vacation in Orlando, where Jamie wanted nothing to do with the Magic Kingdom or with Universal Studios.) Along the way, Jamie kept asking me, as I made our various plans for the day, “are you crazy? are you nuts?” and I would apparently sigh (“deep sigh,” Jamie says when he tells this story), “I am not crazy. I am not nuts.” Gradually this turned into, “what are you, full of cashews/ peanuts/ walnuts” and then into the cornucopia of what are you’s you see here.

Here’s how the list begins:

What are you, a box of All Bran?

What are you, a plate of cheese qasudia?

What are you, full of peanuts?

What are you, a plastic bag of pears?

What are you, a bottle of Hidden Vally Ranch?

…

Well, what ARE you?

* * * * *

I’ve collected my posts about Jamie’s art into a single document: Jamie’s Investigations: The Art of a Young Man with Down Syndrome. You can download it from my Academic.edu page: https://www.academia.edu/29195347/Jamie_s_Investigations_The_Art_of_a_Young_Man_with_Down_Syndrome