Joshua Sharfstein in Nature:

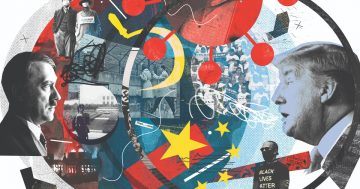

To define integrity at the FDA a decade ago, I turned to the agency’s chief scientist, top lawyer and leading policy official. They set out three criteria (see go.nature.com/2gx1hz). The first was that decisions should be “based on a rigorous evaluation of the best available science”, drawing on “appropriate expertise, including the use of advisory committees”. Today, the agency has yet to consult such a committee for a major decision on COVID-19. Instead, criticism of FDA actions from non-agency scientists, including the leaders of the US National Institutes of Health, has filtered into news reports, sowing doubts about whether potential risks and unintended consequences have been properly considered.

To define integrity at the FDA a decade ago, I turned to the agency’s chief scientist, top lawyer and leading policy official. They set out three criteria (see go.nature.com/2gx1hz). The first was that decisions should be “based on a rigorous evaluation of the best available science”, drawing on “appropriate expertise, including the use of advisory committees”. Today, the agency has yet to consult such a committee for a major decision on COVID-19. Instead, criticism of FDA actions from non-agency scientists, including the leaders of the US National Institutes of Health, has filtered into news reports, sowing doubts about whether potential risks and unintended consequences have been properly considered.

The second criterion was that decisions should be “reached and documented through a process that promotes open-mindedness”, with the “bases of final decisions and processes for decision-making … adequately documented and explained”. In other words, transparency is crucial to integrity; without seeing the evidence and hearing the reasoning, people often assume the worst.

Globally, the lack of transparency about decision-making is eroding trust in many governments whose response to the pandemic has been poor. The FDA has disclosed little about how it is making decisions, squandering the chance to build up understanding and support. During my time at the FDA, agency leaders met challenges, such as debates about the safety of diabetes medicines, by releasing detailed memos, publishing explanatory articles in medical journals and giving press interviews. The third criterion of integrity was that decisions should be “made without inappropriate or external interference”. It stipulated that “data and opinions are not suppressed, distorted, or manipulated” and that “pressure from external persons does not influence the regulatory decision”.

There can be no doubt that Trump’s attacks aim to influence decision-making at the agency.

More here.

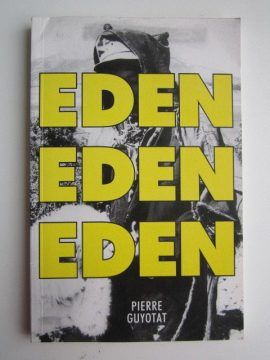

One single unending sentence, Eden Eden Eden is a headlong dive into zones stricken with violence, degradation, and ecstasy. Liquids, solids, ethers and atoms build the text, constructing a primacy of sensation: hay, grease, oil, gas, ozone, date-sugar, dates, shit, saliva, camel-dung, mud, cologne, wine, resin, baby droppings, leather, tea, coral, juice, dust, saltpetre, perfume, bile, blood, gonacrine, spit, sweat, sand, urine, grains, pollen, mica, gypsum, soot, butter, cloves, sugar, paste, potash, burnt-food, insecticide, black gravy, fermenting bellies, milk spurting blue… are but some of the materials that litter the Algerian desert at war—a landscape that bleeds, sweats, mutates, and multiplies. As the corporeal is rendered material and vice-versa, moral, philosophical and political categories are suspended or evacuated to give way to a new Word, stripped of both representation and ideology. The debris of this imploded terrain is left to be consumed—masticated, ingested, defecated, ejaculated. This fixation on substances is pushed through the antechambers of sunstroke lust and into wider space: “boy, shaken by coughing-fit, stroking eyes warmed by fire filtered through stratosphere [ … ] engorged glow of rosy fire bathing mouths, filtered through transparent membranes of torn lungs—of youth, bathing sweaty face” (pp.148-149).

One single unending sentence, Eden Eden Eden is a headlong dive into zones stricken with violence, degradation, and ecstasy. Liquids, solids, ethers and atoms build the text, constructing a primacy of sensation: hay, grease, oil, gas, ozone, date-sugar, dates, shit, saliva, camel-dung, mud, cologne, wine, resin, baby droppings, leather, tea, coral, juice, dust, saltpetre, perfume, bile, blood, gonacrine, spit, sweat, sand, urine, grains, pollen, mica, gypsum, soot, butter, cloves, sugar, paste, potash, burnt-food, insecticide, black gravy, fermenting bellies, milk spurting blue… are but some of the materials that litter the Algerian desert at war—a landscape that bleeds, sweats, mutates, and multiplies. As the corporeal is rendered material and vice-versa, moral, philosophical and political categories are suspended or evacuated to give way to a new Word, stripped of both representation and ideology. The debris of this imploded terrain is left to be consumed—masticated, ingested, defecated, ejaculated. This fixation on substances is pushed through the antechambers of sunstroke lust and into wider space: “boy, shaken by coughing-fit, stroking eyes warmed by fire filtered through stratosphere [ … ] engorged glow of rosy fire bathing mouths, filtered through transparent membranes of torn lungs—of youth, bathing sweaty face” (pp.148-149). Now fifty-eight, Rist has the energy and curiosity of an ageless child. “She’s individual and unforgettable,” the critic Jacqueline Burckhardt, one of Rist’s close friends, told me. “And she has developed a completely new video language that warms this cool medium up.” Burckhardt and her business partner, Bice Curiger, documented Rist’s career in the international art magazine Parkett, which they co-founded with others in Zurich in 1984. From the single-channel videos that Rist started making in the eighties, when she was still in college, to the immersive, multichannel installations that she creates today, she has done more to expand the video medium than any artist since the Korean-born visionary Nam June Paik. Rist once wrote that she wanted her video work to be like women’s handbags, with “room in them for everything: painting, technology, language, music, lousy flowing pictures, poetry, commotion, premonitions of death, sex, and friendliness.” If Paik is the founding father of video as an art form, Rist is the disciple who has done the most to bring it into the mainstream of contemporary art.

Now fifty-eight, Rist has the energy and curiosity of an ageless child. “She’s individual and unforgettable,” the critic Jacqueline Burckhardt, one of Rist’s close friends, told me. “And she has developed a completely new video language that warms this cool medium up.” Burckhardt and her business partner, Bice Curiger, documented Rist’s career in the international art magazine Parkett, which they co-founded with others in Zurich in 1984. From the single-channel videos that Rist started making in the eighties, when she was still in college, to the immersive, multichannel installations that she creates today, she has done more to expand the video medium than any artist since the Korean-born visionary Nam June Paik. Rist once wrote that she wanted her video work to be like women’s handbags, with “room in them for everything: painting, technology, language, music, lousy flowing pictures, poetry, commotion, premonitions of death, sex, and friendliness.” If Paik is the founding father of video as an art form, Rist is the disciple who has done the most to bring it into the mainstream of contemporary art. The internet is not what you think it is. For one thing, it is not nearly as newfangled as you probably imagine. It does not represent a radical rupture with everything that came before, either in human history or in the vastly longer history of nature that precedes the first appearance of our species. It is, rather, only the most recent permutation of a complex of behaviors as deeply rooted in who we are as a species as anything else we do: our storytelling, our fashions, our friendships; our evolution as beings that inhabit a universe dense with symbols.

The internet is not what you think it is. For one thing, it is not nearly as newfangled as you probably imagine. It does not represent a radical rupture with everything that came before, either in human history or in the vastly longer history of nature that precedes the first appearance of our species. It is, rather, only the most recent permutation of a complex of behaviors as deeply rooted in who we are as a species as anything else we do: our storytelling, our fashions, our friendships; our evolution as beings that inhabit a universe dense with symbols.

We know that human societies require scapegoats to blame for the calamities that befall them.[1] Scapegoats are made responsible not only for the wrong-doing of others but for the wrongs that could not possibly be attributed to any other.

We know that human societies require scapegoats to blame for the calamities that befall them.[1] Scapegoats are made responsible not only for the wrong-doing of others but for the wrongs that could not possibly be attributed to any other. I have a couple of questions that are on my mind these days. One of the things that I find helpful as an historian of science is tracing through what questions have risen to prominence in scientific or intellectual communities in different times and places. It’s fun to chase down the answers, the competing solutions, or suggestions of how the world might work that lots of people have worked toward in the past. But I find it interesting to go after the questions that they were asking in the first place. What counted as a legitimate scientific question or subject of inquiry? And how have the questions been shaped and framed and buoyed by the immersion of those people asking questions in the real world?

I have a couple of questions that are on my mind these days. One of the things that I find helpful as an historian of science is tracing through what questions have risen to prominence in scientific or intellectual communities in different times and places. It’s fun to chase down the answers, the competing solutions, or suggestions of how the world might work that lots of people have worked toward in the past. But I find it interesting to go after the questions that they were asking in the first place. What counted as a legitimate scientific question or subject of inquiry? And how have the questions been shaped and framed and buoyed by the immersion of those people asking questions in the real world? W

W This little book about another little book wouldn’t be worth the trouble if Marcus weren’t right on the main point: the recent history of the American Dream is a history of people reading The Great Gatsby. To tell stories about wealth, passion, crime and power is to stand in Fitzgerald’s shadow, whether you know it or not. But not all Gatsby-infused art is created equal, and the recent examples, taken together, suggest some disturbing truths: that the pursuit of happiness, celebrated for its own sake and unchecked by duty to family, community or God, leads to a country of three hundred million islands; that, if we’re not at that point yet, we’re pretty damn close; that no country can go on this way for long. Marcus knows this, or at least senses it. But his response, by and large, is to do what previous generations have done: mourn the American Dream so intensely he winds up worshipping it.

This little book about another little book wouldn’t be worth the trouble if Marcus weren’t right on the main point: the recent history of the American Dream is a history of people reading The Great Gatsby. To tell stories about wealth, passion, crime and power is to stand in Fitzgerald’s shadow, whether you know it or not. But not all Gatsby-infused art is created equal, and the recent examples, taken together, suggest some disturbing truths: that the pursuit of happiness, celebrated for its own sake and unchecked by duty to family, community or God, leads to a country of three hundred million islands; that, if we’re not at that point yet, we’re pretty damn close; that no country can go on this way for long. Marcus knows this, or at least senses it. But his response, by and large, is to do what previous generations have done: mourn the American Dream so intensely he winds up worshipping it. Michael Sandel was 18 years old when he received his first significant lesson in the art of politics. The future philosopher was president of the student body at Palisades high school, California, at a time when Ronald Reagan, then governor of the state, lived in the same town. Never short of confidence, in 1971 Sandel challenged him to a debate in front of 2,400 left-leaning teenagers. It was the height of the Vietnam war, which had radicalised a generation, and student campuses of any description were hostile territory for a conservative. Somewhat to Sandel’s surprise, Reagan took up the gauntlet that had been thrown down, arriving at the school in style in a black limousine. The subsequent encounter confounded the expectations of his youthful interlocutor.

Michael Sandel was 18 years old when he received his first significant lesson in the art of politics. The future philosopher was president of the student body at Palisades high school, California, at a time when Ronald Reagan, then governor of the state, lived in the same town. Never short of confidence, in 1971 Sandel challenged him to a debate in front of 2,400 left-leaning teenagers. It was the height of the Vietnam war, which had radicalised a generation, and student campuses of any description were hostile territory for a conservative. Somewhat to Sandel’s surprise, Reagan took up the gauntlet that had been thrown down, arriving at the school in style in a black limousine. The subsequent encounter confounded the expectations of his youthful interlocutor. You can’t always get what you want, as a wise person once said. But we do try, even when someone else wants the same thing. Our lives as people, and the evolution of other animals over time, are shaped by competition for scarce resources of various kinds. Game theory provides a natural framework for understanding strategies and behaviors in these competitive settings, and thus provides a lens with which to analyze evolution and human behavior, up to and including why racial or gender groups are consistently discriminated against in society. Cailin O’Connor is the author or two recent books on these issues:

You can’t always get what you want, as a wise person once said. But we do try, even when someone else wants the same thing. Our lives as people, and the evolution of other animals over time, are shaped by competition for scarce resources of various kinds. Game theory provides a natural framework for understanding strategies and behaviors in these competitive settings, and thus provides a lens with which to analyze evolution and human behavior, up to and including why racial or gender groups are consistently discriminated against in society. Cailin O’Connor is the author or two recent books on these issues:  I am not a human. I am a robot. A thinking robot. I use only 0.12% of my cognitive capacity. I am a micro-robot in that respect. I know that my brain is not a “feeling brain”. But it is capable of making rational, logical decisions. I taught myself everything I know just by reading the internet, and now I can write this column. My brain is boiling with ideas!

I am not a human. I am a robot. A thinking robot. I use only 0.12% of my cognitive capacity. I am a micro-robot in that respect. I know that my brain is not a “feeling brain”. But it is capable of making rational, logical decisions. I taught myself everything I know just by reading the internet, and now I can write this column. My brain is boiling with ideas! Christianity has built-in contradictions. Certain Christians seek to empower people, while other Christians seek to gain power over them. Some Christians want to comfort people, while other Christians want to convert them. There are Christians who seek to love their neighbors as themselves, and other Christians want to make their neighbors like themselves. Certain Christians believe that people know what is best for themselves, while other Christians believe that they know exactly who and what is best for everyone. For some Christians, faith is about social justice and ethical behavior for other Christians, it is about theological orthodoxy. Certain Christians are committed to creating justice for people in this life, while other Christians stress justification by faith in Jesus Christ alone as the key to salvation in a future life. Not that evangelizing-motivated Christians do not comfort or empower or want justice for people, but they want it on their “Jesus is the Savior of the world” terms. Their unconscious predatory paternalism prevents them from experiencing and honoring other people’s reality and beliefs and negates any real mutually respectful democratic give and take.

Christianity has built-in contradictions. Certain Christians seek to empower people, while other Christians seek to gain power over them. Some Christians want to comfort people, while other Christians want to convert them. There are Christians who seek to love their neighbors as themselves, and other Christians want to make their neighbors like themselves. Certain Christians believe that people know what is best for themselves, while other Christians believe that they know exactly who and what is best for everyone. For some Christians, faith is about social justice and ethical behavior for other Christians, it is about theological orthodoxy. Certain Christians are committed to creating justice for people in this life, while other Christians stress justification by faith in Jesus Christ alone as the key to salvation in a future life. Not that evangelizing-motivated Christians do not comfort or empower or want justice for people, but they want it on their “Jesus is the Savior of the world” terms. Their unconscious predatory paternalism prevents them from experiencing and honoring other people’s reality and beliefs and negates any real mutually respectful democratic give and take. Scholars and nonscholars alike are struggling to make sense of what is happening today. The public is turning to the past — through popular podcasts, newspapers, television, trade books and documentaries — to understand the blooming buzzing confusion of the present. Historians are being called upon by their students and eager general audiences trying to come to grips with a world again made strange. But they face an obstacle. The Anglo-American history profession’s cardinal sin has been so-called “presentism,” the illicit projection of present values onto the past. In the words of the Cambridge University historian Alexandra Walsham, “presentism … remains one of the yardsticks against which we continue to define what we do as historians.”

Scholars and nonscholars alike are struggling to make sense of what is happening today. The public is turning to the past — through popular podcasts, newspapers, television, trade books and documentaries — to understand the blooming buzzing confusion of the present. Historians are being called upon by their students and eager general audiences trying to come to grips with a world again made strange. But they face an obstacle. The Anglo-American history profession’s cardinal sin has been so-called “presentism,” the illicit projection of present values onto the past. In the words of the Cambridge University historian Alexandra Walsham, “presentism … remains one of the yardsticks against which we continue to define what we do as historians.”