Stanley Crouch (1945 – 2020)

Ruth Bader Ginsburg (1933 – 2020)

Sunday Poem

A Portrait in Greys

Will it never be possible

to separate you from your greyness?

Must you be always sinking backward

into your grey-brown landscapes—and trees

always in the distance, always against a grey sky?

……………………… Must I be always

moving counter to you? Is there no place

where we can be at peace together

and the motion of our drawing apart

be altogether taken up?

…………………………………. I see myself

standing upon your shoulders touching

a grey, broken sky—

but you, weighted down with me,

yet gripping my ankles,—move

……………………. laboriously on,

where it is level and undisturbed by colors.

by William Carlos Williams

Saturday, September 19, 2020

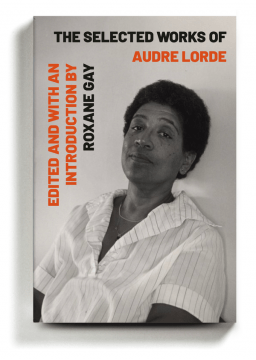

A Timely Collection of Vital Writing by Audre Lorde

Parul Seghal at the NYT:

Lorde loved to be in dialogue, loved thinking with others, with her comrades and lovers. She is never alone on the page. Even her short essays come festooned with long lines of acknowledgment to those who have sharpened their ideas. Ghosts flock her essays. She writes to the ancestors and to women she meets in the headlines of the newspaper — missing women, murdered women, naming as many as she can, the sort of rescue and care for the dead that one sees in the work of Saidiya Hartman and Christina Sharpe. In “The Cancer Journals,” in which she documented her diagnosis of breast cancer, she noted: “I carry tattooed upon my heart a list of names of women who did not survive, and there is always a space left for one more, my own.”

Lorde loved to be in dialogue, loved thinking with others, with her comrades and lovers. She is never alone on the page. Even her short essays come festooned with long lines of acknowledgment to those who have sharpened their ideas. Ghosts flock her essays. She writes to the ancestors and to women she meets in the headlines of the newspaper — missing women, murdered women, naming as many as she can, the sort of rescue and care for the dead that one sees in the work of Saidiya Hartman and Christina Sharpe. In “The Cancer Journals,” in which she documented her diagnosis of breast cancer, she noted: “I carry tattooed upon my heart a list of names of women who did not survive, and there is always a space left for one more, my own.”

more here.

Audre Lorde Interview (1982)

The world’s central banks are starting to experiment. But what comes next?

Adam Tooze in The Guardian:

Adam Tooze in The Guardian:

Are we seeing the end of the supremacy of the US dollar? With soaring government spending and gaping deficits are we on the cusp of a great surge of inflation? In light of the extreme financial measures required by the Covid-19 crisis and the alarming polarisation of US politics, the markets can be forgiven for asking such dramatic questions.

But it is worth reminding ourselves that as recently as March, the whole world was crying out for dollars. And far from fearing inflation, the problem actually facing central banks is how to avoid sliding into deflation. Falling prices are a disaster because they squeeze debtors – think negative equity in housing markets – and create a vicious circle of postponed purchases, leading to falling demand and further deflation.

In response to the threat of deflation, there are, indeed, changes afoot. But these take the form not of some dramatic collapse, but of a series of subtle but important adjustments in central bank policy.

More here.

America’s Dire Inequality Demands a New Conceptual Framework

Lynn Parramore interviews Lance Taylor over at INET:

Lynn Parramore interviews Lance Taylor over at INET:

Lynn Parramore: In your new book, you name wage repression as the biggest driver of inequality in the U.S. over the last several decades. Your conclusion differs from many who have studied the issue, such as Thomas Piketty, who theorized that inequality is caused mainly by a tendency of profits to run ahead of the growth rate in the economy. What’s different about your take?

Lance Taylor: Piketty & Co. deserve a lot of credit for using tax and other data to estimate how income distribution differs across households over 200 years. The question is, what explains these differences?

I wanted to analyze how income differences among various kinds of households (poor, middle class, and affluent) came about over time. That meant drilling down into macroeconomic indicators as well as the data associated with the various industries in which people worked and the streams of income they received from them.

Özlem Ömer and I assembled what we needed by reworking Congressional Budget Office data along the lines of the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) National Income Accounts. This allowed us to look at both macroeconomics and individual industries or sectors — 16 in all.

We studied changes in the structure of payments, employment, and output of products and services across these 16 sectors. What we found is that except in volatile and low-profit agriculture and mining sectors, real wages grew less rapidly than productivity since around the time of Reagan’s presidency. Wage shares decreased, but profit shares increased at the industry and macro levels, and the money from those profits ended up in the pockets of business owners and the wealthy instead of being shared.

For the most part, Americans workers have been working more productively, but they haven’t been getting paid for it due to forces that aren’t natural and inevitable. Wage repression doesn’t just happen.

More here.

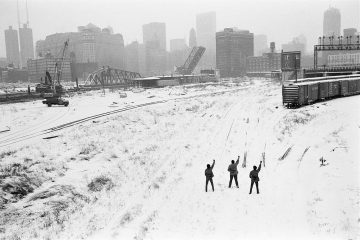

Antifa Dust

Michael Scott Moore in the LA Review of Books:

Michael Scott Moore in the LA Review of Books:

IN 2005, I covered a raucous political rally in the German town of Gera, near Weimar, featuring neo-Nazis who wanted to field a candidate for chancellor during the national election that brought Angela Merkel to power. Their man was a belligerent politician with a mustache named Udo Voigt. Skinheads and more conventional-looking Germans — including Birkenstock-wearing young families — gathered in the dappled sunlight of an enclosed park for speeches and music. Local police had surrounded the park’s perimeter to keep counterprotesters marching against the rally in Gera’s cobblestoned streets from clashing with the skinheads. Police turn up whenever neo-Nazis march in postwar Germany — without them there would be riots.

A far-right band in the park had just finished a set of racist thrash music while tech workers arranged the stage for a speech by Voigt. Behind them a banner for the NPD, Germany’s most significant neo-Nazi party at the time, fluttered in the wind. I happened to ask a pregnant woman pushing a stroller across the grass why she voted NPD. Familie und Vaterland, she said. Policies favoring German families, German priorities. She felt alienated by Gerhard Schröder’s Social Democrats and Merkel’s more conservative CDU/CSU — the major parties — and although she cast herself as a simple dissident against the German mainstream, the racist fog of the rally was hard to ignore.

She gave me a gentle smile as she explained her problem with Germany’s conventional parties. “They put up with too much corruption,” she said.

I took notes, which a lot of people regarded with suspicion. Udo Voigt mounted the stage between black columns of amplifiers and spoke with his sleeves rolled up, like a man with work to do. He gave the usual populist far-right line: anti-immigrant, anti-establishment, anti-journalist, pro-German blood and soil. The next time I saw a similar event was 10 years later, when US networks started to televise Donald Trump’s campaign rallies.

More here.

The Political Economy of Saving the Planet

Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin talk to C. J. Polychroniou in Boston Review:

Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin talk to C. J. Polychroniou in Boston Review:

C. J. Polychroniou: How does the coronavirus pandemic, and the response to it, shed light on how we should think about climate change and the prospects for a global Green New Deal?

Noam Chomsky: At the time of writing, concern for the COVID-19 crisis is virtually all-consuming. That’s understandable. It is severe and is severely disrupting lives. But it will pass, though at horrendous cost, and there will be recovery. There will not be recovery from the melting of the arctic ice sheets and the other consequences of global warming.

Not everyone is ignoring the advancing existential crisis. The sociopaths dedicated to accelerating the disaster continue to pursue their efforts, relentlessly. As before, Trump and his courtiers take pride in leading the race to destruction. As the United States was becoming the epicenter of the pandemic, thanks in no small measure to their folly, the White House cabal released its budget proposals. As expected, the proposals call for even deeper cuts in healthcare support and environmental protection, instead favoring the bloated military and the building of Trump’s Great Wall. And to add an extra touch of sadism, “the budget promotes a fossil fuel ‘energy boom’ in the United States, including an increase in the production of natural gas and crude oil.”

More here.

The Wages of Whiteness

Hari Kunzru in the NY Review of Books:

In 1981 members of a revolutionary group called the Black Liberation Army robbed a Brink’s armored van at the Nanuet Mall in Rockland County, just outside New York City. In the robbery and a subsequent shootout with police, a guard and two police officers were killed. Assisting this Black Nationalist “expropriation” operation were four white Communists, members of a faction of the Weather Underground called the May 19 Communist Organization. They acted as getaway drivers, and three of the four were unarmed, yet they were convicted of murder and sentenced to decades in prison.

One of these white participants, Kathy Boudin, told a skeptical Elizabeth Kolbert, who interviewed her in prison for a 2001 profile in The New Yorker, that she didn’t know anything about the target of the robbery, how it was planned, who was going to commit it, or the intended purpose of the money. She was approached only a day before it took place. This wasn’t mere ignorance, she explained, but a political act of faith. She told Kolbert:

My way of supporting the struggle is to say that I don’t have the right to know anything, that I don’t have the right to engage in political discussion, because it is not my struggle. I certainly don’t have the right to criticize anything. The less I would know and the more I would give up total self, the better—the more committed and the more moral I was.

More here.

The paradox of Graham Greene

Nicholas Shakespeare in The Spectator:

Joseph Conrad’s death made Graham Greene feel, at 19, sitting on a beach in Yorkshire, ‘as if there was a kind of “blank” in the whole of contemporary literature’. Greene’s own death in 1991, aged 87, had a similar effect on many younger writers, myself included. For John le Carré, his most obvious successor, Greene had ‘carried the torch of English literature, almost alone’. His cool fugitive presence, in Martin Amis’s phrase, had been there all our reading lives. In an age of diminishing faith, he had used Catholic parables in a way that lent them a power beyond their biblical origins, mining the gospels rather as le Carré has mined the Cold War. Shaking his hand in Moscow in 1987, Mikhail Gorbachev spoke for an international audience: ‘I have known you for some years, Mr Greene’ — although it was unclear whether as an admirer of his novels, or if Russia’s president had seen his name in intelligence reports concerning Latin America.

Joseph Conrad’s death made Graham Greene feel, at 19, sitting on a beach in Yorkshire, ‘as if there was a kind of “blank” in the whole of contemporary literature’. Greene’s own death in 1991, aged 87, had a similar effect on many younger writers, myself included. For John le Carré, his most obvious successor, Greene had ‘carried the torch of English literature, almost alone’. His cool fugitive presence, in Martin Amis’s phrase, had been there all our reading lives. In an age of diminishing faith, he had used Catholic parables in a way that lent them a power beyond their biblical origins, mining the gospels rather as le Carré has mined the Cold War. Shaking his hand in Moscow in 1987, Mikhail Gorbachev spoke for an international audience: ‘I have known you for some years, Mr Greene’ — although it was unclear whether as an admirer of his novels, or if Russia’s president had seen his name in intelligence reports concerning Latin America.

About Greene’s character, less consensus reigns. Congenitally elusive, he refused to appear on television. ‘I feel I’ve got a copyright on my life,’ he explained to me, ‘and that people I know should have a copyright on theirs.’ How much of his secretiveness was vanity is hard to tell. Unable to pronounce the letter ‘r’, his instinct was for self-effacement — ‘I am so shy’ were his first words to Kim Philby’s Russian wife. Yet co-habiting the same skin — ‘faintly sunburned, with the texture of fine dry silk’, recalled one mistress, Jocelyn Rickards — there writhed a provocative exhibitionist whose love-making with Rickards as they travelled first-class by train to Southend was conducted in blatant view of those on the platforms.

Definitely, there were aspects of his life that he hated, even if others thought it a good thing to be him, and pinched his identity. When Greene learned of one impersonator being jailed in Assam, he proposed to interview him for Picture Post. But his double jumped bail, so the real Graham Greene couldn’t visit India for fear of arrest.

More here.

The Ruth Bader Ginsburg Fandom Was Never Frivolous

Megan Garber in The Atlantic:

In 2014, Kate Livingston created a quirky Halloween costume for her 12-week-old son. It featured a black, sleeved onesie. And a white silken collar. And a pair of large, plastic-rimmed glasses. Livingston snapped a picture of the cosplaying infant—he provided the cool scowl—and then added a caption, in blunt all-caps, to the photo she took: “I DISSENT.” Ruth Baby Ginsburg was born.

In 2014, Kate Livingston created a quirky Halloween costume for her 12-week-old son. It featured a black, sleeved onesie. And a white silken collar. And a pair of large, plastic-rimmed glasses. Livingston snapped a picture of the cosplaying infant—he provided the cool scowl—and then added a caption, in blunt all-caps, to the photo she took: “I DISSENT.” Ruth Baby Ginsburg was born.

Justices of the Supreme Court have traditionally existed above the fray. They wear body-obscuring black robes, stay stoic at the State of the Union address, and prioritize a long-view approach to human events. But Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who died today at age 87, changed that model, because Ruth Bader Ginsburg lived within the fray: Particularly in her later years, she was a justice who was also a celebrity. There was Notorious RBG, the meme and the Tumblr and the book. There was On the Basis of Sex, the 2018 biopic telling the story of Ginsburg’s early years as a professor and a litigator. There was RBG, the documentary. There were Kate McKinnon’s swaggering impressions on Saturday Night Live (“You’ve been Ginsburned!”). And there was the array of RBG-themed goods: the prayer candles, the dolls, the coloring books, the jewelry. There are the collections of RBG-inspired collars. Hers is a visible fandom.

More here.

Saturday Poem

A Pile of Fish

—for Paul Otremba

Six in all, to be exact. I know it was a Tuesday

or Wednesday because the museum closes early

on those days. I almost wrote something

about the light being late—; the “late light”

is what I almost said, and you know how we

poets go on and on about the light and

the wind and the dark, but that day the dark was still

far away swimming in the Pacific, and we had

45 minutes to find Goya’s “Still Life with Bream”

before the doors closed. I’ve now forgotten

three times the word Golden in the title of that painting

—and I wish I could ask what you think

that means. I see that color most often

these days when the cold, wet light of morning

soaks my son’s curls and his already light

brown hair takes on the flash of fish fins

in moonlight. I read somewhere

that Goya never titled this painting,

or the other eleven still lifes, so it’s just

as well because I like the Spanish title better.

“Doradas” is simple, doesn’t point

out the obvious. Lately, I’ve been saying

dorado so often in the song I sing

to my son, “O sol, sol, dorado sol

no te escondes…” I felt lost

that day in the museum, but you knew

where we were going having been there

so many times. The canvas was so small

at 17 x 24 inches. I stood before it

lost in its beach of green sand and

that silver surf cut with pink.

I stared while you circled the room

like a curious cat. I took a step back,

and then with your hands in your pockets

you said, No matter where we stand,

there’s always one fish staring at us.

As a new father, I am now that pyramid

of fish; my body is all eyes and eyes.

Some of them watch for you in the west

where the lion sun yawns and shakes off

its sleep before it purrs, and hungry,

dives deep in the deep of the deep.

by Tomás Q. Morín

from the Academy of American Poets

Friday, September 18, 2020

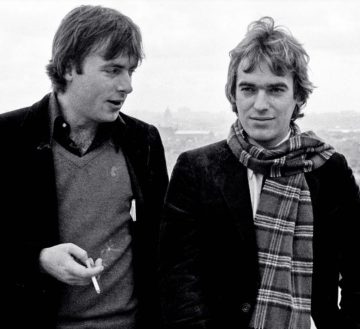

Martin Amis, Christopher Hitchens and the long road to reaction

Thomas Meaney in The New Statesman:

It would hardly have surprised Christopher Hitchens, his unsanguine views of the afterlife under no bushel, that among the trials and stations awaiting his departed soul there would be passage through a Martin Amis novel (he had already endured being packed into The Pregnant Widow in the character of Nicholas Shackleton). Inside Story – the Fleet Street tease of the title notwithstanding – evinces a protective, even proprietary attitude towards the goods to be delivered. The cover features an arresting image of the two grands amis – both formerly of this parish – on the cusp of their prime. Hitchens is on the left, holding his cigarette mid-abdomen like a paintbrush. His as yet unravaged face seems to be gauging whether his last remark has landed with Amis, who looks into the distance, appearing simultaneously satisfied and anxious.

It would hardly have surprised Christopher Hitchens, his unsanguine views of the afterlife under no bushel, that among the trials and stations awaiting his departed soul there would be passage through a Martin Amis novel (he had already endured being packed into The Pregnant Widow in the character of Nicholas Shackleton). Inside Story – the Fleet Street tease of the title notwithstanding – evinces a protective, even proprietary attitude towards the goods to be delivered. The cover features an arresting image of the two grands amis – both formerly of this parish – on the cusp of their prime. Hitchens is on the left, holding his cigarette mid-abdomen like a paintbrush. His as yet unravaged face seems to be gauging whether his last remark has landed with Amis, who looks into the distance, appearing simultaneously satisfied and anxious.

The novel, however, is more than a testament to a sacred bond. Inside Story whiplashes the reader between more decades (roughly from the start of Amis’s career in 1973 with The Rachel Papers, right up to the age of Trump) and more figures than his memoir Experience (perhaps Amis’s best book to date, and certainly his most finely structured).

More here.

Renormalization has become perhaps the single most important advance in theoretical physics in 50 years

Charlie Wood in Quanta:

In the 1940s, trailblazing physicists stumbled upon the next layer of reality. Particles were out, and fields — expansive, undulating entities that fill space like an ocean — were in. One ripple in a field would be an electron, another a photon, and interactions between them seemed to explain all electromagnetic events.

In the 1940s, trailblazing physicists stumbled upon the next layer of reality. Particles were out, and fields — expansive, undulating entities that fill space like an ocean — were in. One ripple in a field would be an electron, another a photon, and interactions between them seemed to explain all electromagnetic events.

There was just one problem: The theory was glued together with hopes and prayers. Only by using a technique dubbed “renormalization,” which involved carefully concealing infinite quantities, could researchers sidestep bogus predictions. The process worked, but even those developing the theory suspected it might be a house of cards resting on a tortured mathematical trick.

“It is what I would call a dippy process,” Richard Feynman later wrote. “Having to resort to such hocus-pocus has prevented us from proving that the theory of quantum electrodynamics is mathematically self-consistent.”

Justification came decades later from a seemingly unrelated branch of physics.

More here.

Bill Gates on the Pandemic: ‘You Hope It Doesn’t Stretch Past 2022’

David Wallace-Wells in New York Magazine:

Every year, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation releases a Goalkeepers report, tracking the world’s progress toward the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals. The news is almost always pretty good. This year’s edition is … not like that. “Almost every time we have opened our mouths or put pen to paper,” the Gateses write in the report’s introduction, “we have celebrated decades of historic progress in fighting poverty and disease. But we have to confront the current reality with candor: This progress has now stopped.” Their annual report tracks global progress on 18 different metrics. “In recent years, the world has improved on every single one. This year, on the vast majority, we’ve regressed.”

Every year, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation releases a Goalkeepers report, tracking the world’s progress toward the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals. The news is almost always pretty good. This year’s edition is … not like that. “Almost every time we have opened our mouths or put pen to paper,” the Gateses write in the report’s introduction, “we have celebrated decades of historic progress in fighting poverty and disease. But we have to confront the current reality with candor: This progress has now stopped.” Their annual report tracks global progress on 18 different metrics. “In recent years, the world has improved on every single one. This year, on the vast majority, we’ve regressed.”

For a nonmedical civilian, Bill Gates has occupied an unusually central role in the story of the coronavirus pandemic almost since it arose. Gates, who spent much of the past decade warning the world about the risks of a respiratory pandemic, found himself funding a flu study this spring that was among the first documenting community spread of COVID-19 in the U.S. He has devoted much of the foundation’s resources to infectious disease and global immunization programs over the years and now has funded a lot of expedited research into possible coronavirus vaccines and treatments — indeed, he helped pre-fund the manufacturing of seven candidate vaccines, long before knowing whether they would work.

More here.

The Life and Times of Murray Gell-Mann

The U.S. Has an Empathy Deficit

Judith Hall and Mark Leary in Scientific American:

America is a country in deep pain. The coronavirus pandemic, racial injustice, economic insecurity, political polarization, misinformation and general daily uncertainty dominate our lives to the point that many people are barely able to cope. And life wasn’t exactly a cakewalk before 2020. Out of all the fears, stresses and indignities our citizens are living with, there emerges a kind of primal insecurity that undermines every aspect of life right now. It’s no wonder that anxiety, depression and other psychological problems are on the rise.

America is a country in deep pain. The coronavirus pandemic, racial injustice, economic insecurity, political polarization, misinformation and general daily uncertainty dominate our lives to the point that many people are barely able to cope. And life wasn’t exactly a cakewalk before 2020. Out of all the fears, stresses and indignities our citizens are living with, there emerges a kind of primal insecurity that undermines every aspect of life right now. It’s no wonder that anxiety, depression and other psychological problems are on the rise.

Whenever people are troubled or hurting or dealing with serious problems, they want to feel that other people understand what they are going through and are concerned. But opportunities to give and receive empathy feel less than adequate these days: decreased social interaction, online get-togethers, air hugs and masked conversations are not quite up to the task—and people are often so preoccupied with their own struggles that they aren’t as attuned to other people’s problems as they otherwise might be.

On top of that, everyone is confronted with people who seem indifferent. Some of our leaders have dismissed the seriousness of their fellow Americans’ plight. Some ordinary Americans convey a lack of concern when they refuse to socially distance and wear face coverings, or criticize those who do. The fact that a recent Gallup poll showed that roughly a third of the country doesn’t think there’s a problem with race relations suggests that many people aren’t grasping other people’s perspectives.

More here.

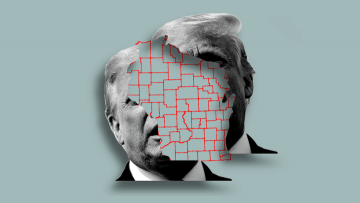

An Experiment in Wisconsin Changed Voters’ Minds About Trump

David A. Graham in The Atlantic:

No state has haunted the Democratic Party’s imagination for the past four years like Wisconsin. While it was not the only state that killed Hillary Clinton’s presidential hopes in 2016, it was the one where the knife plunged deepest. Clinton was so confident about Wisconsin that she never even campaigned there. This year, it is one of the most fiercely contested states. The Democrats planned to hold their convention in Milwaukee, before the coronavirus pandemic forced its cancellation. Donald Trump is also making a strong play for Wisconsin. Trump’s weaknesses with the electorate are familiar: Voters find him coarse, and they deplore his handling of race, the coronavirus, and protests. One recent YouGov poll found that just 42 percent of Americans approved of his performance as president, while 54 percent disapproved. But when the pollsters asked about Trump’s handling of the economy, those attitudes reversed: 48 percent approved and 44 percent disapproved, despite the havoc wreaked by the pandemic.

No state has haunted the Democratic Party’s imagination for the past four years like Wisconsin. While it was not the only state that killed Hillary Clinton’s presidential hopes in 2016, it was the one where the knife plunged deepest. Clinton was so confident about Wisconsin that she never even campaigned there. This year, it is one of the most fiercely contested states. The Democrats planned to hold their convention in Milwaukee, before the coronavirus pandemic forced its cancellation. Donald Trump is also making a strong play for Wisconsin. Trump’s weaknesses with the electorate are familiar: Voters find him coarse, and they deplore his handling of race, the coronavirus, and protests. One recent YouGov poll found that just 42 percent of Americans approved of his performance as president, while 54 percent disapproved. But when the pollsters asked about Trump’s handling of the economy, those attitudes reversed: 48 percent approved and 44 percent disapproved, despite the havoc wreaked by the pandemic.

The high marks that voters give Trump’s economic record are a key obstacle to Democratic efforts to win back Wisconsin and other upper-midwestern states. But a surprisingly effective progressive effort this spring to undermine Trump’s approval ratings on the economy provides a model for how the president’s opponents can hurt Trump where he’s strongest—and maybe even tip the election to Joe Biden.

Changing voters’ minds is famously difficult. Recent national campaigns have spent more effort on increasing turnout—getting sympathetic voters to go to the polls—than on winning over new supporters. Political scientists and pollsters have found that as the country grows more negatively polarized, fewer true swing voters are up for grabs.

But the Wisconsin effort, notable for both its approach and its scale, seems to have found some success.

More here.