by Sherman J. Clark

We do not need philosophers to tell us that human beings matter. Various versions of that conviction is already at work everywhere we look. A sense that people are worthwhile shapes our law, which punishes cruelty and demands equal treatment. It animates our medicine, which labors to preserve lives that might seem, by some external measure, not worth the cost. It structures our families, where we care for the very young and the very old without calculating returns. It haunts our politics, where arguments about justice presuppose that citizens possess a standing that power must respect. But what does it mean to say human beings are worthwhile? And why might it be worthwhile to ask what me mean when we say we matter?

We do not need philosophers to tell us that human beings matter. Various versions of that conviction is already at work everywhere we look. A sense that people are worthwhile shapes our law, which punishes cruelty and demands equal treatment. It animates our medicine, which labors to preserve lives that might seem, by some external measure, not worth the cost. It structures our families, where we care for the very young and the very old without calculating returns. It haunts our politics, where arguments about justice presuppose that citizens possess a standing that power must respect. But what does it mean to say human beings are worthwhile? And why might it be worthwhile to ask what me mean when we say we matter?

When we speak of dignity, worth, or the respect owed to persons, we are not engaging in idle abstraction. These concepts do real work. They justify constraints on what the powerful may do to the vulnerable. They ground claims to equality that might otherwise seem like mere sentiment. They explain both our moral outrage when persons are degraded and our moral hesitation when we are tempted to treat others as mere instruments.

It is true, then, that we do not need philosophy to tell us that human beings have value. But it is equally true that we are remarkably adept at forgetting this in our actions. We affirm, often sincerely, that all human lives matter, while behaving as though some lives matter far more than others—some kinds of suffering are urgent while others are tolerable, some deaths tragic while others barely register. The conviction is present, but it is unevenly applied, easily displaced by fear, convenience, habit, or interest.

One reason to reflect on the nature and source of human worth, then, is not to discover that worth exists, but to see more clearly how our practices fall short of what we already claim to believe. Thinking about dignity is a way of making our commitments explicit, of exposing the quiet hierarchies we smuggle into our moral lives while insisting, in the abstract, on equality. Philosophy here does not supply a new value; it sharpens our awareness of how badly we sometimes honor the one we already profess.

There is another reason to think carefully about human worth. Our moral lives are increasingly populated by beings and entities that share some, but not all, of the features we implicitly rely on when we claim respect for ourselves. Fetuses, non-human animals, people in irreversible comas, the dead, emerging artificial intelligences, even ecosystems—all press on the boundaries of our moral vocabulary. They are not alike, and nothing is gained by pretending that they are. But neither can we think well about how to treat them if we treat human worth as a brute fact beyond examination.

One way to broaden and deepen our thinking about respect is to ask ourselves why we take ourselves to be entitled to it. The question is not meant to undermine human standing, but to clarify it. By making explicit the considerations that matter to us when we insist on dignity—vulnerability, forms of life, the capacity to flourish, participation in shared practices—we become better equipped to respond to morally adjacent cases without either collapsing distinctions or retreating into exclusion. Reflection, here, is not a search for an essence, but a discipline of moral attention.

That is what this essay is about. I am not trying to invent or even defend concern for human worth but rather reflect on a concern we already purport to live by. The question is not whether human beings matter, but what we are doing—and what we might do better—when we say that they do.

One common move, when pressed on these questions, is to invoke the language of intrinsic value. Philosophers and ordinary speakers alike appeal to “intrinsic worth,” “inherent dignity,” or “basic respect” as though these phrases settled questions rather than raised them. The word intrinsic functions, in much moral discourse, as a kind of placeholder—a way of declaring that worth does not depend on external conditions without specifying what it does depend on. We are told that human beings possess value in themselves, not merely as means to other ends, but the nature of this self-grounded value remains obscure.

There are understandable reasons for this reticence. To inquire into the grounds of human worth might seem to put that worth at risk. If we specify the property that makes humans valuable, we invite the question of what happens when the property is absent or diminished. We fear that grounding equality in any particular capacity will license inequality among those who possess that capacity in different degrees. We worry that the inquiry itself presupposes a vantage point outside the moral community from which humans can be assessed—and that such a vantage point is either unavailable or corrupting.

These concerns are not foolish. But the strategy of avoidance carries its own costs. To say that worth is intrinsic stabilizes our practices without illuminating them. It tells us that humans matter but not why; it asserts equality but cannot explain it; it leaves the hardest questions—about marginal cases, about non-human creatures, about emerging forms of intelligence—not resolved but merely postponed.

The most natural response to this difficulty is to identify some capacity that humans possess and that justifies their special standing. Rationality is a traditional candidate: we matter because we can reason, deliberate, and grasp universal principles. Autonomy offers a related answer: we matter because we can set ends for ourselves and are not merely subject to external determination. Consciousness, sentience, moral agency—each has been proposed as the property that elevates humans above the merely natural order.

Each of these proposals captures something morally relevant. Rationality, autonomy, and consciousness are not arbitrary features; they bear on what can be done to a creature and what that creature can do. But each proposal also fractures the equality it seeks to ground. Rationality varies across individuals; some humans possess it in diminished measure or not at all. Autonomy can be compromised by illness, youth, or circumstance. Consciousness admits of degrees. If worth tracks capacity, then worth must vary with capacity—and the egalitarian aspiration is undone.

Philosophers have developed repair strategies: potential capacity, typical species functioning, membership in a kind that characteristically possesses the relevant property. But these repairs are revealing. They tacitly acknowledge that the property itself cannot do the grounding work, and they reintroduce precisely what the theory sought to explain. Why should potential matter if only actual capacity grounds worth? Why should species membership matter if worth is not about species but about properties? The problem is structural: any property robust enough to ground worth will vary in ways that undermine equality; any property distributed equally enough to preserve equality will be too thin to explain why it matters.

At this point, it may help to step back and reconsider what we are doing when we make claims about dignity at all. We have been searching for the property that grounds human worth, as though dignity were a feature of individuals waiting to be discovered. But when we assert that human beings possess dignity, we are not only making a metaphysical claim about the furniture of the universe; we are doing something. We are affirming a normative commitment, signaling moral membership, and binding ourselves to practices of restraint, recognition, and care. Dignity talk is, among other things, a speech act—a way of constituting and maintaining the moral relations in which we stand.

Consider equality. When we say that all persons are equal, we are not reporting an empirical finding—the claim is obviously false if taken as a description of actual capacities or achievements. Nor are we making a metaphysical discovery, as though equality were a feature of the world independent of our attitudes. We are, rather, adopting a stance: committing ourselves to treating persons as equals, to structuring institutions on egalitarian lines, to resisting hierarchies that would rank human beings by worth.

To notice the performative dimension of dignity talk is not to reduce it to mere performance. The claim is not that dignity is “just” a social construction with no connection to anything real. It is rather that the reality to which dignity talk responds may exceed our capacity to articulate it fully. We may be pointing at something genuine—some feature of persons or of our relation to them that truly matters—while remaining unable, due to cognitive limitation or the poverty of our concepts, to say exactly what it is. The performative work of dignity talk proceeds while the metaphysical questions remain open. And the fact that dignity claims function as commitments does not mean they are unconstrained; they remain answerable to history, to experience, and to the forms of life they sustain or corrode.

This perspective suggests a shift in emphasis. Rather than seeking the ground of dignity and then deriving practices from it, we might attend to the practices themselves—asking what they do, whom they serve, and whether they conduce to lives worth living. The question becomes not “What property justifies respect?” but “What ways of relating to one another make possible the kinds of lives we have reason to value?”

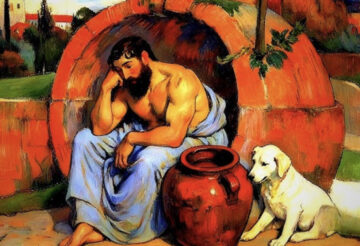

Framed this way, the question finds natural resources in the tradition of virtue ethics. The eudaimonist approach, running from Aristotle to the present, does not ask “What rules must I follow?” or “What outcomes should I maximize?” but “What kind of person should I become?” and “What constitutes a good human life?” These questions direct attention away from properties that might ground worth and toward practices that might constitute flourishing.

Eudaimonia—the Greek term usually translated as “flourishing” or “happiness”—is not mere affect. It is not simply feeling good; it is having a life one can feel good about, a life that merits affirmation. This means that eudaimonia has a normative dimension built into it. A flourishing life is not just a pleasant life; it is a life of a certain quality, one that meets standards not entirely of the liver’s own making.

Respectworthiness is not external to flourishing but partially constitutive of it. To live well is, among other things, to live in a way that warrants respect—one’s own and others’. And to treat others well is to engage with them in ways that support their capacity to live such lives. Respect and flourishing are not two separate items, one grounding the other; they are aspects of a single complex achievement.

This approach does not solve the grounding problem so much as relocate it. We stop asking “What property makes humans worthy of respect?” and start asking “What practices of mutual regard make it possible for humans to flourish?” The latter question is not easier, but it is tractable. It invites empirical inquiry, historical reflection, and practical experimentation. It accepts disagreement as the normal condition of ethical life rather than as a scandal to be overcome. And it evaluates our practices by their fruits rather than by their conformity to antecedent metaphysical requirements.

This is, in a sense, a classical move. Aristotle approaches the good in just this spirit: we can say true things about it, aim at it, recognize instances of it, without being able to give a complete theoretical account. The limitation is in us—in our cognitive reach and our conceptual vocabulary—not necessarily in the subject matter. Practical wisdom has always proceeded under conditions of incomplete understanding.

A serious objection now presents itself. If we frame ethics in terms of human flourishing, have we not simply begged the question we set out to address? We wanted to know what makes humans worthy of moral concern, and we have answered: their flourishing matters. But why should human flourishing matter, except to humans? Are we not simply expressing a provincial attachment to our own kind, dressed up in philosophical vocabulary?

The objection has two edges. The first concerns individualism: if flourishing is understood as a private achievement, something each person accomplishes alone, then the eudaimonist framework risks collapsing into a sophisticated form of self-interest. Why should I care about your flourishing except insofar as it contributes to mine? The second concerns species chauvinism: if the flourishing that matters is specifically human flourishing, then we have merely relocated human specialness rather than explaining it. The dog, the dolphin, the intelligent machine might all ask why human lives should take precedence over their own forms of thriving.

These are not peripheral worries. They go to the heart of whether the eudaimonist reframing can do the work required of it. If the framework cannot escape human self-concern, it has not advanced beyond the familiar evasions; it has merely given them a new idiom.

The response to both edges of the objection lies in recognizing that flourishing is not, at bottom, an individual achievement. Consider the pick-and-roll in basketball. It is a form of excellence that cannot be executed by one player alone; it emerges only from the coordinated action of two players who read and respond to each other in real time. Neither player “owns” the excellence; it belongs to their joint activity. Or consider the corps de ballet, where sixteen dancers form a pattern that no individual dancer embodies. The beauty of the whole is not the sum of sixteen individual performances; it is a property of their coordination, their mutual attentiveness, their shared practice.

These examples reveal something about the structure of human flourishing more generally. Aristotle’s famous claim that humans are political animals means, in part, that human excellence is achieved in and through relationships. The virtues are not private possessions but relational capacities: courage is displayed in contexts that involve others; justice is unintelligible apart from social life; even temperance and practical wisdom take their shape from the communities in which they are exercised.

If this is right, then flourishing is inherently shared. It depends on institutions, norms, and patterns of mutual recognition that no individual can create or sustain alone. To care about my own flourishing is already to care about the conditions that make flourishing possible—and those conditions include your flourishing and the quality of our relations. The individualism objection thus dissolves: the eudaimonist framework does not reduce others’ good to a means to my own but recognizes that our goods are intertwined in ways that preclude such reduction.

But this answer addresses only half the objection. Grant that flourishing is shared among humans; can the insight extend beyond the human community? If we participate in common practices and institutions with other humans, what about creatures whose forms of life differ radically from our own?

Here the eudaimonist framework suggests a different kind of move. The question to ask about a dog is not “How much is this creature like a human?” but “What does flourishing look like for a dog?” Dogs have lives that can go well or badly as dog lives. They can be healthy or sick, engaged or bored, secure or anxious. They have characteristic activities—running, smelling, playing, bonding—whose exercise constitutes their form of thriving. To treat a dog well is to attend to these features of canine existence, not to measure the dog against human standards and find it wanting.

Consider a boy and his dog. The companionship they share is a genuine practice, not reducible to the goods either party could achieve alone. The boy learns attentiveness, responsibility, and a kind of interspecies communication. The dog receives care, stimulation, and membership in a social unit that satisfies deep canine needs. Their relationship is asymmetrical—the boy has capacities and responsibilities the dog lacks—but the asymmetry need not be domination. What makes it non-dominating is precisely the attention each pays to the other’s form of flourishing: the boy does not treat the dog as a furry human, and the dog does not demand what only humans can provide.

This is the easier case, of course. Boy and dog can form a mutually enriching bond because their goods are compatible, even complementary. What about cases where flourishing conflicts—where the mosquito’s thriving requires my blood, or the invasive species’ expansion threatens an ecosystem, or human settlement displaces creatures who were there first? The eudaimonist framework does not pretend to resolve these conflicts algorithmically. Some conflicts are tragic rather than resolvable, and any framework that pretends otherwise is suspect. What this approach offers is a discipline of attention: we are to consider the forms of life involved, the goods at stake, the relationships that structure our choices. We remain answerable for the decisions we make. The framework keeps us honest about what we are doing when we subordinate one creature’s flourishing to another’s.

This essay has not solved the problem of human worth. It has not identified the property that grounds dignity or the algorithm that resolves all conflicts. What it has offered is a reframing: a way of approaching questions of worth that does not require metaphysical foundations we cannot supply and do not need.

We are finite creatures with limited cognitive capacities and imperfect languages. The full truth about why persons matter may exceed our grasp. But this does not leave us empty-handed. We can attend to the practices by which we treat one another—asking whether they conduce to flourishing, whether they respect the forms of life involved, whether they create relationships of mutual enrichment or exploitation. We can hold our commitments to dignity and equality as revisable practices rather than fixed discoveries, remaining open to learning that we have drawn the boundaries of moral concern too narrowly.

The eudaimonist approach does not eliminate hard choices; it clarifies what is at stake in making them. It asks us to consider not only what rules we follow but what kinds of persons we are becoming, not only what outcomes we produce but what relationships we inhabit. In a world of genuine plurality—where different creatures flourish in different ways, where goods sometimes conflict, where uncertainty is the permanent human condition—this may be the best we can do. It is also, I venture, enough.